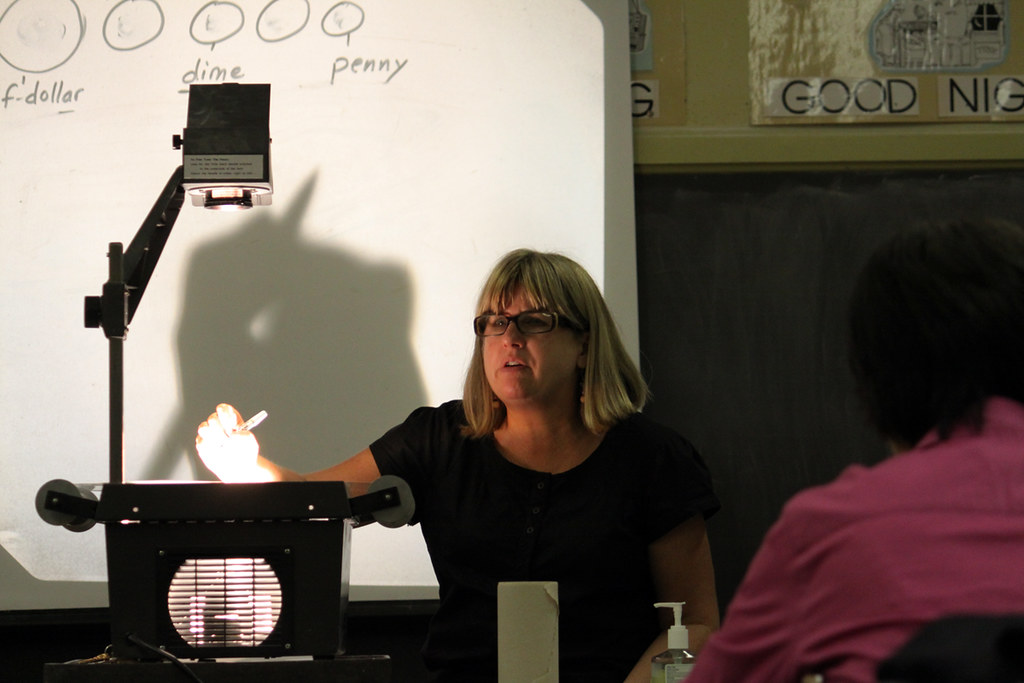

“Half dollar,” she says loudly and clearly as she taps her black marker against the largest circle. The class repeats after her, matching her volume and inflection in voices cloaked in a tangy Cantonese accent. All of the students are Chinese immigrants. For some, this is their first time attending school , in either country.

Derek Shen moves with a carefulness and curiosity akin to someone who recently regained a lost sense. These traits are evident as he sets down his backpack on the warm concrete outside, then tucks his long legs beneath him as he takes a seat beside it, silently absorbing the garden-like qualities of SF State’s Humanities building courtyard. When he’s settled, he removes from a front compartment on his backpack a sleek, silver digital voice recorder not unlike the ones used by working journalists.

But the 18-year-old accounting major does not aspire to be the next Truman Capote. With his index finger hovering above the notorious red dot of the record button, he admits before his interview, “Sometimes I record my professors’ lectures so I can go back and listen to them later if I don’t understand.”

Having resided in the United States–Berkeley, California in particular–for just six months, Shen is one of a growing number of Americans, international students, and immigrants who identify as English as a Second Language (ESL) learners.

Originally from Changzhi, a small town about 300 miles southwest of Beijing, China, Shen applied to SF State after completing his high school requirements because, according to him, “America has the best business programs in the world.” While he acknowledges, without an ounce of bravado, the ease with which he can tackle his math homework, Shen admits that his English fluency requires more attention.

“Sometimes the teachers ask a question, and I can’t answer immediately,” he says. “I take time to really think about it and translate it in my mind before answering.”

Outside the classroom, Shen faces even more difficulty when he encounters those who may not have the same patience with the language barrier.

“Last week I went to the gym on campus, and someone at the front desk asked me a very simple question, but I couldn’t answer it, and I felt a little embarrassed,” he says. Shen was required to fill out paperwork before using the fitness facilities, but he couldn’t understand where to write certain information. Shen maintains that “most people are patient and will repeat themselves more slowly, but a few people just say, ‘Never mind.’”

For Fayola Perry, the hurdle is slightly different. Native to Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago (she moved to the United States when she was seven years old), Perry’s first language was English. Nevertheless, the journalism and Africana Studies double-major grapples with language rules that are specific to American English.

“My accent is now really refined after having been in the American school system for the past decade and a half, but I remember so vividly being frustrated with having to repeat myself so frequently,” she says.

And in the journalism department, which places an especially heavy emphasis on grammatical precision and correct spelling, Perry must contend with an extra layer of criticism.

“I write words like ‘favorite’ and ‘color’ with an ‘-our,’ instead of just ‘-or,’” she says, stressing the sound in each of the words. “And I remember one of my professors marking that on my paper and telling me to ‘watch spelling.’ It’s one of those things that’s innate in how I write. We [in Trinidad and Tobago] speak what’s considered British English, and my lens doesn’t filter [those words] out as being spelled improperly.”

Similarly, the students in Holly’s class find themselves lost in translation, particularly when dealing with English-speaking tourists who frequent the establishments at which they are employed in Chinatown. One of Stevens’ students, Bao Huan Huang, works at a restaurant in that neighborhood. When this happens, she either finds someone nearby to translate, or says in a tone and rhythm that suggest more than sufficient practice, “Sorry, I don’t know English.”

Universal language

In order to reinforce this new vocabulary, Stevens incorporates mathematics into the lesson by giving the class sample problems. She asks things like, “If I have two quarters, two dimes, two nickels, and one penny, how much do I have?” Students immediately bow their heads, almost in reverence, over their worksheets as they compute the problem with pencils and fingertips.

The voice of the first pupil to attempt an answer tiptoes to Stevens’ ears, loud enough to be heard, but not so loud that it will draw unwanted attention if it’s incorrect. “81 cents,” says the anonymous mathematician.

“Good job!” Stevens replies, without skipping a beat. Incidentally, the rest of the class echoes her in this statement of positive reinforcement–an attempt to further expand their vocabularies–so that for every subsequent right answer, the room becomes a sounding board of encouragement.

SHINE on

On an expectedly dark and foggy Wednesday evening in SF State’s Humanities building, an unexpected level of energy buzzes in room 548. Upwards of 100 students mingle excitedly as they indulge in a mélange of finger foods–pizza, grapes, cookies, chips and salsa. The crowd is as diverse as the snack platter; the students’ ages range from 18-45, and amid the chatter rises colorful accents suggesting a variety of national origins.

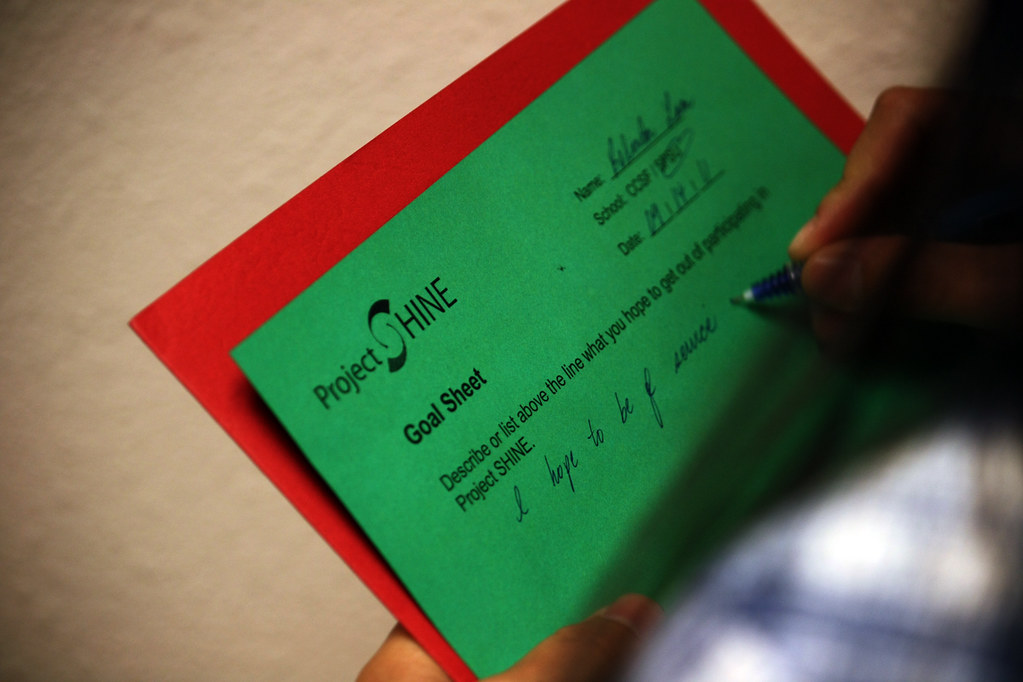

The noise dies down courteously when a young woman with a bob haircut and a broad grin (later identified as Laura Marsh) stands at the front of the classroom. “Welcome, everyone,” she begins in an enunciated tone, “to Project SHINE orientation.”

Established over 30 years ago in Philadelphia at Temple University’s Intergenerational Center, Project SHINE provides immigrants and refugees with programs and services in workforce development, health literacy, and civic engagement, all of which work to reduce the feelings of social isolation often associated with living in a foreign country. Project SHINE also funds ESL and citizenship classes, which are held for free at the City College of San Francisco, among other institutions in California and eight other states including Minnesota, Texas, Colorado, and New York.

Gail Weinstein founded SF State’s Project SHINE 15 years ago. The university linguist lost her fight to ovarian cancer in December 2010, but the program continues to thrive under the direction of Dr. Maricel Santos. This year, SF State’s Project SHINE will send 200 students to each of CCSF’s campuses to work voluntarily as coaches under master ESL teachers. Holly Stevens and company at the North Beach/Chinatown branch of CCSF are engaged in one such class; Derek Shen is one such coach.

“I feel a little nervous because I’m not sure I can do the job well,” admits Shen a couple of days before his first ESL coaching class, which is located at the Mission branch of CCSF and deals primarily with Spanish-speaking students. His nerves, however, are overshadowed by his excitement in meeting people from different countries and forming a rapport with his assigned master teacher.

Not all SHINE coaches are former ESL learners, though. Most are undergraduate students enrolled in Language in Context and Second Language Acquisition, both within the English department at SF State, who can volunteer 20 hours for SHINE this semester in lieu of another assignment. Others, like program leader Chelsea Lo, are in pursuit of their Masters in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (MATESOL) at SF State.

Lo, who earned her bachelors degree in business at the University of Southern California, made an abrupt transition to teaching English after a slightly jarring realization at a college close to her alma mater.

After having studied abroad in China, Lo returned to the U.S. inspired and wanting to teach ESL classes at the community college level. “I met a lady who taught an ESL class at Irvine Valley College, and asked if I could volunteer,” says the Southern California native. “She initially said yes, but then she talked to her supervisor, who said they’d never had an intern before. There were a lot of complications with things like liability waivers…the infrastructure wasn’t set up for someone like me to get involved.” But according to Lo, Project SHINE operates the opposite way, making it “so easy to get experience doing that I want to do someday [as a career].”

And while Shen may not hold the same aspirations as Lo (he plans to take his business degree back to China and start his own yet-to-be-determined business there), he is certainly receiving the experience he hoped for.

Despite his initial nerves, Shen says that once he entered the classroom he “felt very relaxed. The teacher [Nancy McNee] told me my English is good, and that gave me confidence.” He says that although most of the students are older than he is, they call him Teacher and thank him for helping them. Shen also inadvertently receives lessons in a third language through his work with Project SHINE.

“When I help them with something, they say ‘gracias,’ and I think, ‘Oh, maybe [that means] thank you,” says Shen, who plans to tackle Spanish next. “Everybody is a teacher for me,” he adds. “Everyone has an advantage, and I can learn something from them.”

Game of Life

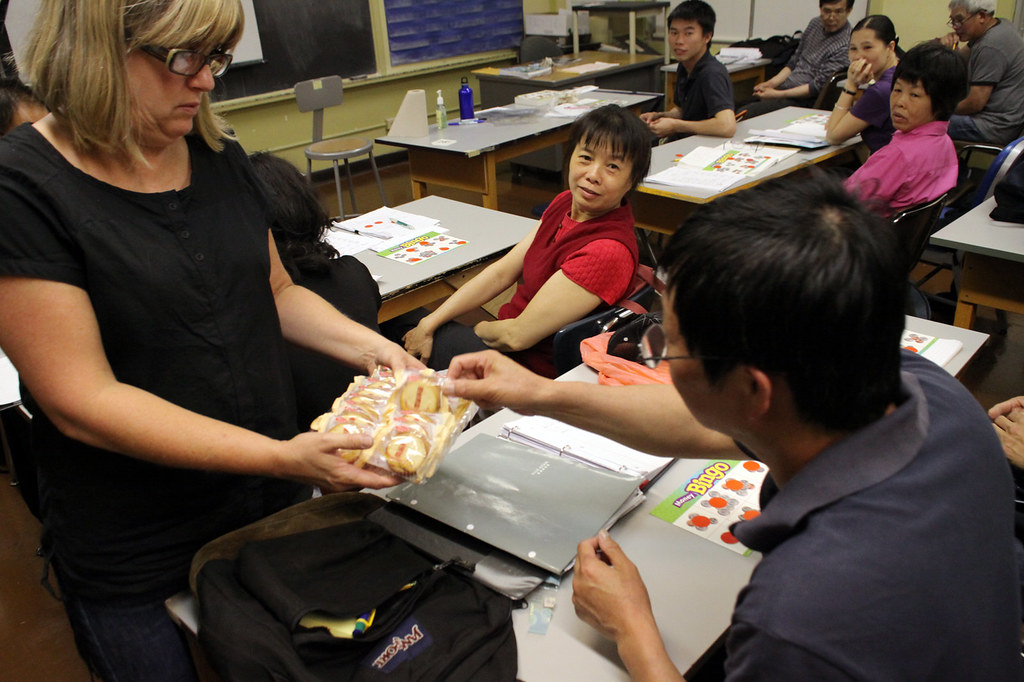

The North Beach/Chinatown class concludes with a classic game that challenges the night’s previous lessons. Chu, the SHINE coach assigned to Stevens’ class, passes out thin squares of cardboard marked with a matrix of random clusters of coins, along with red circular markers. Holly explains–and Chu translates in Cantonese to ensure clarity of the rules–that she will read out a number, and that if they see the corresponding value on their cards, to mark it with a red dot. The object of the game is to completely cover their board in red dots; the first student to achieve this “black out” wins a small packet of crackers.

“The name of the game is Bingo,” says Stevens, which unleashes a flood of giggles from the rest of the class. In Cantonese, “bin go” means “Who is that?”

Some of the more strategic students try to quickly compute the amounts on their cards and write the number next to the coins, but the seasoned teacher catches them and reminds them, firmly but compassionately, “When you’re out in the real world at the grocery store, you won’t have pencils to calculate the change you need.” When Chu relays this to them in Cantonese, they all respond with a thoughtful, drawn-out “Oh,” and set their pencils down.

Anticipation rises in the room with each number Holly calls out. Suddenly, Xiu Lian Su jumps up from her seat, punches a scrunchie-encircled arm in the air, and shouts, “Bingo!” before surrendering to her own laughter and collapsing back into her desk.

Stevens distributes the prize, and then offers the rest of the class the same crackers. Some hesitate at first because they didn’t win the game, but after some reassurance they select their own package of crackers.

“It’s become a tradition I can’t escape,” says Holly says of the snacks to nobody in particular. “A lot of them come here right after work and are starving.”

Thanks to Project SHINE, Derek Shen and the students in Stevens’ class–and hundreds of others like it across the country–are inching their way toward linguistic sufficiency in the United States, one lesson at a time. With their unwavering enthusiasm and openness to the variety of “teachers” surrounding them, they will soon be able to unleash their arsenal of multilingual strength and contribute to their communities in more than one language.

Bingo.

Translation Services in New York • Nov 15, 2016 at 1:55 am

Translation is very most important for every, person who is not aware about others language, they should consult with an language interpreter.