The Uncounted

San Francisco’s homeless deaths have gone unreported by the city and county since 2019.

May 2, 2022

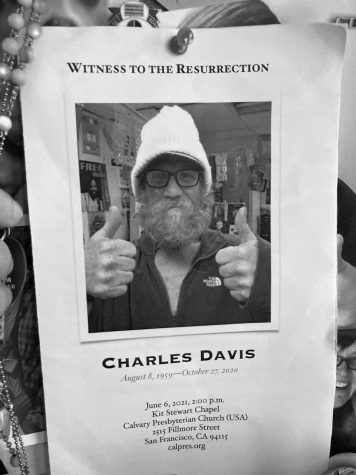

The last time Reverend Victor Floyd saw his friend Charles Davis, he was smiling.

Davis had spent much of the last 45 years unhoused, living on the streets of San Francisco and Seattle. It was early 2020, the start of the pandemic, when he thought he had finally found a home in temporary housing at the Tilden Hotel on Taylor Street. Floyd, a Reverend at San Francisco’s Calvary Presbyterian Church, had helped him secure the spot.

When he called Davis to let him know about the hotel, Davis came straight to the church, his smile beaming through his bushy red beard. Davis asked Floyd to buy him some ramen and ice cream. Floyd gladly complied and supplied his friend with a white grocery bag of ramen and another filled with cartons of ice cream.

Davis, a wiry redheaded man originally from Vancouver, Washington, stood outside in the sun and smiled, excited this might be the chance he needed to get his life back on track after surviving the brutal San Francisco streets for years. His bag full of ice cream melted in the sun’s hot rays, but Davis didn’t care; he just wanted to get to his new place.

“I prefer the ice cream soft anyways,” Floyd recalled Davis saying.

That was the last time Floyd would see his friend. Only a few months later, Davis died alone in his room at the Tilden, according to a copy of his death certificate obtained by Xpress. He was 61.

In 2018, two years prior to Davis’s death, there were 135 reported homeless deaths in San Francisco, according to the San Francisco Department of Public Health. But since the last report was published in January 2019, San Francisco’s total number of homeless deaths has gone unreported by the city and county. While some data documenting COVID-19-related homeless deaths has been released, official data is unavailable and is not expected to be published until mid-2022, according to Barry Zevin, a Medical Director at the SFDPH.

For the City and County of San Francisco, Zevin is tasked with collecting this data from an 8,000-plus population primarily centered in the City’s South of Market and Tenderloin neighborhoods — a population that included Davis. The data has not been made public; however, in an article published by the Guardian, Zevin supplied data from a small sample size in Spring 2020 that he has not since provided despite multiple requests.

In response to a request for data on homeless deaths, David Serrano Sewell, the chief operating officer at the San Francisco Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, directed reporters to Zevin and the SFDPH. In a follow-up email, Sewell said he did not have this data. The medical examiner’s office confirmed they did not have a public portal or public access to this information.

“Unfortunately, the analysis is not complete on 2019-2020 data, and it is not available,” said Zevin in an email to Xpress on December 9, 2021.

Cities with similar or larger populations of people experiencing homelessness have released data regularly. The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health released their findings from 2020-2021 in April 2022. The data show that 1,727 people experiencing homelessness died in Los Angeles County. However, the city’s homeless population is significantly larger than San Francisco’s.

That year, the LA County’s homeless population topped 58,000, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

LA County also releases weekly data on the number of people experiencing homelessness who died of COVID. Currently, the City of San Francisco estimates that 13 people experiencing homelessness died of COVID-19 through May 2, 2022.

“That’s all held by the medical examiner’s office. And with the caveat that this population is really hard to keep track of,” said Denny Machuca-Grebe, the public information officer at the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

He added that although the DHSH does not keep formal data, it does have informal information about the number of homeless people who died in single residence occupancies, but that information is not currently available to the public and will not be until an unspecified time in 2022. He did not elaborate further.

While the SFDPH has not made the data on homeless deaths available, advocates and activists in the community have seen firsthand the toll the pandemic has had on people experiencing homelessness, people like Davis.

“It had such a dramatic impact where everything just shut down,” said Kelley Cutler, a Human rights Organizer at the Coalition on Homelessness in San Francisco. “All of these things that people don’t necessarily think of that are part of this system that supports folks who are forced to live on the street, like a big part of that system, got shut down.”

One of those services is Street Sheet, a San Francisco newspaper that focuses on the issues of poverty and housing published by the Coalition on Homelessness. The coalition gives the publication to people experiencing houselessness for free to sell and earn money for themselves.

Davis worked as a Street Sheet vendor and, in a 2017 issue, authored an article about his tumultuous early life. He left home at the age of 16 to escape an abusive father and spent some time in juvenile hall before living with his aunt and uncle in Castle Rock, a small Washington farm town far from the city and its towering skyscrapers. He stayed there until he was 17, and then he went out on his own. That’s how he lived up until his death — alone.

Davis spent time traveling throughout the country with stops in San Francisco, Nebraska, North Carolina and Seattle before finally landing back in San Francisco in the late 2010s.

Like Davis, many people experiencing homelessness are also transitory, which means they go from location to location over a short period of time. This experience is, for some, what keeps them alive. However, when they enter some form of stable housing, it gives their bodies a chance to rest.

“A lot of folks when it comes to homelessness, by the time that they finally get into an SRO, it’s not uncommon that people will then die by the time that the system has finally gotten them into housing,” said Cutler. “They’re physically just so worn down and have been through so much trauma that’s when their body is finally able to rest. [It’s not] uncommon for folks to die that way.”

After returning to San Francisco, Cutler suggested Davis start selling the Street Sheet at Calvary Presbyterian Church, where he met Reverend Floyd.

“Charles lived his life in italics. I said he was the redheaded stepchild I never knew I wanted,” said Floyd, 57, despite being a few years younger than Davis.

The church set up a table for Davis during the coffee hour in their Social Hall after worship, and Davis would sell his Street Sheet and chat with the parishioners. He befriended Laura and Brian Elbogens and their two young children.

Laura, who works as a watercolor painter and illustrator, is originally from Indianapolis, Indiana. Brian, who works at a San Francisco real-estate startup and grew up in the East Bay, met Davis in 2014.

They had seen him at church; he had become a familiar face but hadn’t spoken with him much. But one day, they were taking the 22 bus up Fillmore Street to the church and saw Davis.

“He started a conversation because our children were dressed up in pageant costumes for the Calvary Christmas Pageant as like a giraffe and a rooster or something. And he was just really engaging [and] very funny,” Laura said.

During the service, the Elbogens invited him to spend Christmas Eve dinner with them and Laura’s Family from Indiana, along with Brian’s family and some church friends. That became a tradition for the Elbogens as Davis’s bushy red beard became a frequent appearance at their table, especially during the holidays. At these dinners, Davis was often at the center of attention.

“He stole the show,” Brian laughed. “I talked to Victor [Floyd], and we were joking that in a different life, he would be like the head of enterprise at Salesforce. He just had this gift of talking and building trust and relationships and telling his story.”

When the pandemic hit, it became harder to see him. The Elbogens quarantined, and his sporadic drop-ins were hard for them to navigate. They would leave supplies and other things for him outside, but they had to set boundaries.

In late Spring 2020, Floyd set out to get Davis some housing. He contacted Cutler at the Coalition on Homeless, and she directed him to some city officials who could help him.

Floyd used the fact that he was a pastor at this church in Pacific Heights to call city officials and pressure them to help him find Davis housing. He received a call from the person in charge of the shelter-in-place program at the time, which according to Floyd, said he would help him this one time but never ask him for anything again.

The pandemic has forced more people out on the streets to survive, with state and local initiatives aimed at protecting them. Project Roomkey, which provided funding for cities to lease hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness, was one such initiative. However, because people who took part in the project were considered part of non-congregate shelters, they were still regarded as homeless.

Floyd still remembers how happy Davis was to have a shelter and have his own space. Davis had hopes that the city would make the Tilden Hotel permanent housing for the homeless.

“He was so excited. It was like Christmas morning. He was just elated that he would have a place just to be and to be safe,” Floyd said.

Davis’ cause of death was due to an overdose on cocaine and fentanyl, according to his death certificate. His ashes remain in Floyd’s office, and he feels unsure what to do with them.

“It’s kind of bizarre; his ashes are very heavy,” he said. “Every once in a while, I say, ‘Hello,’ and he’s with me right now.”