Oliver Michelsen is a fourth-year journalism student with a minor in history. Born in Virginia, he moved around frequently throughout his childhood, living...

Oliver Michelsen and Rene Ramirez

The Bay Area astronomers who capture the night sky.

May 13, 2022

Andy Macica caught his first picture of a supernova by accident. He shot Messier 51, what he refers to as either M51 or “the Whirlpool Galaxy,” 23 million lightyears away on his home telescope. When he later read that a supernova had been recorded, he checked his photos from days earlier to see that he had captured the small blur of a dying star in a far-off galaxy.

Today, Macica lives in San Jose and works as a part-time telescope operator and tour guide at Lick Observatory. Across both his journals and photos, he has documented upwards of 2,500 astronomical events in his more than 30-year amateur astronomy career, a large number of them from his backyard.

“The telescopes [at Lick] are large and powerful enough that I’ve been able to see quasars… about 2 billion light-years away to 8 or even 10 billion light-years away,” Macica said. “They may be very small; they may look like a star, but the fact that you’re looking at something that far away is quite interesting.”

Quasars, he later explained, are highly luminous objects expected by astronomers to be powered by supermassive black holes.

Macica is just one of the Bay Area-based astronomers who has devoted their life to documenting the expansive array of astronomical objects and events constantly floating in and out of our sky’s field of vision. He, and many others, spend most of their nights peering through the light pollution of cities like San Jose and San Francisco, hoping to capture another quasar, comet or supernova on film.

Macica doesn’t live on the mountain like some of the full-time astronomers but said that Mt. Hamilton, located about 20 miles outside of San Jose, is the “primo location” for astronomy in the Bay Area. Before he worked as a docent, or guide, at the observatory, he would come up and take astrophotos in the area due to its distance from the city’s light pollution.

Eventually, after years of volunteering and observation, Macica learned to operate the observatory’s 36-inch and 40-inch telescopes. The 36-inch telescope was constructed in the 1880s, he recounted, and it requires two people to manually aim and calibrate its focus.

The road leading up to Lick Observatory, located at the peak of Mt. Hamilton, is narrow, winding and, in many spots, lacking a guard rail. Macica makes the drive a few times a week to lead private tours for students and tourists as well as to make use of the observatory’s equipment for viewings.

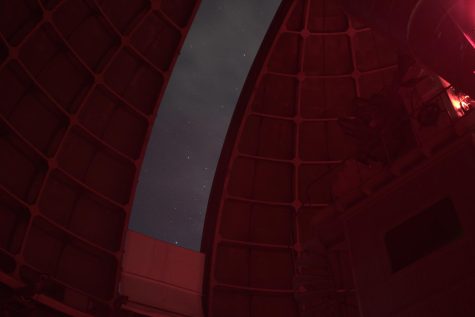

After showing groups the facilities during the day, with the help of another longtime docent, Pat Maloney, Macica opened the roof of the main observatory’s 36-inch telescope and began setting up for viewing.

With a limited window of time, the two locked onto Gamma Leonis (γ Leo), a binary star system that flickers blue and gold in the eyepiece located 130 lightyears away. Maloney dryly joked that though the far-off stars were often referred to as the “Berkeley Stars,” he preferred to call them “Davis Stars” after his own alma mater.

One late night after a tour group eventually left around 11 p.m., hours after their driver would’ve preferred, the two astronomers joked about “the dead body in the basement.”

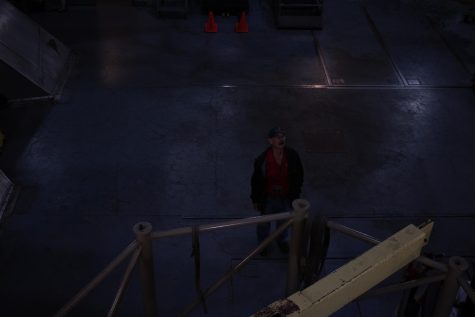

Directly below the massive telescope at the center of a circular concrete room that you need a hardhat to enter sits the black brick grave of James Lick, the observatory’s founder. Metal support beams and wooden boxes with backup lenses and early 20th-century documents showing advanced astronomical computations fill the rest of the already crowded space.

[robo-gallery id=”21955″]

Throughout his tours, Macica excitedly answered every question asked of him and looked on in awe with the rest of the group as the 120-inch telescope operator opened the massive domed roof for sunset. Sunlight filled the room as the massive deep space imaging device began to turn and rotate towards the opening.

In the Bay Area, there are a number of organizations that promote amateur astronomy and photography for newcomers to the scene, as Macica does.

Groups like the San Francisco Amateur Astronomers hold monthly “star parties” in the Presidio and on top of Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County for its members, while other organizations such as the Sonoma County-based Striking Sparks hold events at the Robert Ferguson Observatory in Santa Rosa to promote astronomy and scientific education to local students.

Elinor Gates, the chief astronomer at Lick Observatory, lives on Mt. Hamilton year-round, just a two-minute drive from the summit and main observation facilities. She said that while one of the main goals of the observatory is the training and education of University of California student astronomers, Lick hosts a number of events encouraging the community to make use of its facilities.

Though their ability to hold these events was greatly limited by the pandemic, the observatory has been able to more recently get back to hosting private tours and astrophotography nights. These often bring in a mix of amateur and professional astronomers.

“Professional astronomers are often looking for the scientific content of an image that’s taken in a particular color, whereas the amateur astrophotographers are more looking for beauty,” she explained. “Both have wonderful merits. We want to underscore more about the universe, but it’s also amazing to appreciate the beauty of what is out there in the sky.”

Regardless of experience, both sides of the spectrum deal with the same obstacles in the form of light pollution and unpredictable weather conditions. Cameras capture images by allowing light to hit the camera’s sensor for a fraction of a second.

Astrophotographers use what are called long exposures in order to capture the faint light given off by distant stars. When shooting near a city, these 10 to 30-second exposures take in the light emitted from buildings and street lamps, often drowning out the astronomical subject of the photo.

More than 20 miles away from San Jose, photos captured from the peak of Mt. Hamilton often still come out with a light glow from the city’s lights.

Truman Farr is an astrophysics student at SF State and an amateur astrophotographer from Los Angeles. Though he’d been interested in astronomy from a young age, Farr didn’t begin pointing his camera upwards until the end of high school.

When shooting with his home equipment from his southern California driveway, Farr uses an array of lens filters and scope settings to drown out as much of the light pollution as he can. However, he said completely blocking it out would be impossible.

Winds and fog also have the potential to completely drown out or blur an image beyond recognition. Farr explained that in San Francisco, a clear night’s viewing could be completely enveloped in fog within 20 minutes, eliminating any possibility of capturing photos for the night.

Despite the extra effort and equipment required, Farr holds a unique fondness for the astrophotography process.

“Just growing up loving space and loving how insanely beautiful these objects are… it may be the challenge of it,” he explained. “I love the fact that behind every photo that some amateur astrophotographer posts, there’s a lot of effort that goes into it. Like in some cases, there’s 20 plus hours of either shooting or editing or setting up.”

[robo-gallery id=”21952″]

Many nights Brian Padgett, a longtime amateur astrophotographer born and raised in Sonoma county, sets up in the front driveway of his Santa Rosa home with his 14-year-old son, Aiden. Before they can begin viewing and imaging on their home telescope, they carry out the often arduous process of aligning it with the North Star, Polaris.

Padgett explained that one of his biggest inspirations for getting involved in astronomy was his son’s passion for the subject at a young age. He recalled many nights when the duo would stay up late looking at the images that their telescope was capturing. The following morning Padgett would look at all the footage captured and begin the hours-long process of layering and editing to pull out the best image possible.

Things took a turn for the worse, however, when the 2017 Tubbs Fire ravaged Northern California and much of Sonoma County.

Padgett and his family had just enough time to get out of their house and get to safety, but in the process, they lost their house, all of Padgett’s astronomy equipment, and the hard drives holding his extensive archive of family and astrophotos.

“It took a long time to kind of get back to being able to do it again,” he recalled. “I did replace a scope, not all my scopes, over time. I then started attaching and building that out and was pretty much just doing visual astronomy for quite a while.”

Padgett, as well as his son, are docents at the Robert Ferguson Observatory and have spent the last few years building back their astrophotography equipment. Though he now only has one telescope, it is a behemoth.

The 400+ pound LX850 mount and 14-inch lens Meade telescope is covered with a thin thermal coat to keep temperatures consistent and avoid condensation on the internal mirror or lenses. Another aspect that makes Padgett’s scope unique is its ability to lock onto and track astronomical objects such as stars and distant galaxies.

Because the Earth is constantly rotating, advanced tracking systems like the one Padgett uses are a necessity for deep space imaging. Without one, a camera is unable to follow the stars, albeit not noticeable to the human eye, constant movement across the sky and images will begin to streak.

Once he aligned his system with Polaris, Padgett pulled out a packet of eyepatches. He explained that by wearing one over your dominant eye, you build “night vision,” which allows you to see more when peering through the scope’s eyepiece.

[robo-gallery id=”21958″]

Now, ready to view, Padgett explained some of the other challenges he faces when photographing from his neighborhood.

In addition to wiping out most of his belongings, the fire also fundamentally changed the landscape for taking night sky photos in the Sonoma County area. Where there used to be dense foliage blocking the lights of Fountaingrove, a neighborhood visible from Padgett’s driveway, now stand barren trees that allow light to fill the sky and drown out photos of the stars.

Another issue that he and other astrophotographers deal with is timing.

Prior to the pandemic, Padgett constantly traveled for work, causing him to miss the opportunity to capture multiple astronomical events. Objects and events like that of a passing comet or asteroid provide a one-time-only opportunity for a photo. If you miss them for any number of reasons, your opportunity may be lost forever.

Gates recalled being lucky enough to capture a photo of the comet NEOWISE from her backyard on Mt. Hamilton back in March of 2020 before it quickly faded back into obscurity.

“The sky is constantly changing, and things aren’t static. [W]e have great objects, like new supernova explosions that one day, it’s not there, and the next day, the star explodes… They’re bright for maybe a few months and then fade away,” she explained. “Some objects, you have even less time to study.”

The astronomy community in the Bay Area is a thriving one, due in large part to people like Gates, Padgett and Macica. Padgett teaches courses explaining the basics of astrophotography and brings his telescope with him to local schools and stargazing nights to stoke interest in local students and budding astronomers.

Macica, who spends most days either on Mt. Hamilton or in his backyard gazing at astronomical bodies, said his favorite part of the work nowadays is passing his passion on to a new generation of stargazers.

“I just like seeing the excitement in their faces, the questions they ask… I’m more in the autumn of my life. They’re in the spring of their life. So seeing the excitement coming from the younger generation means a lot to me.”

Oliver Michelsen is a fourth-year journalism student with a minor in history. Born in Virginia, he moved around frequently throughout his childhood, living...