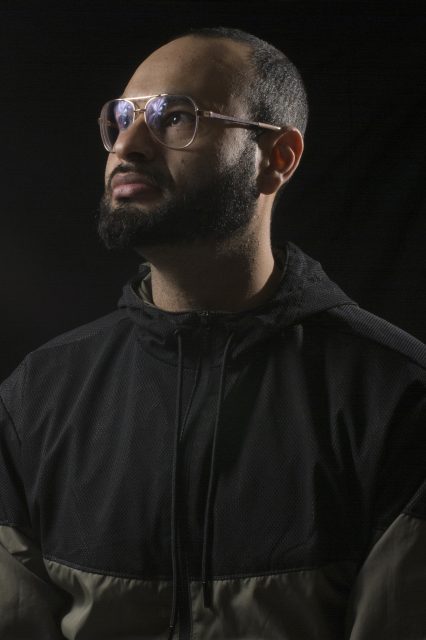

Thirty-year-old Jose Valenzuela runs his fingers through his scruffy beard as his eyes pierce through teardrop prescription glasses and out the living room window. His unblinking stare isn’t directed at anything outside but into his memory. A melancholic expression takes over his face as he recalls, “I’ve only seen my dad cry two times in my life.”

Looking back on his formative years, Valenzuela has come to accept and even admire his dad for trying to shield him from the strains of life. However, he also reaped the consequences of his father’s actions when later in life he struggled to deal with sensitive situations on his own.

Dr. Weinberger, psychologist at Stanford University, says, “In families where the parents themselves are repressors, the child learns that the expression of emotions is to be avoided.” His studies have proven that bottling up emotions is a gateway to anxiety, depression, and other mental health illnesses.

“Anger and sadness are an important part of life, and new research shows that experiencing and accepting such emotions are vital to our mental health,” Tori Rodriguez, practicing psychotherapist, says. “Attempting to suppress thoughts can backfire and even diminish our sense of content.”

Valenzuela was raised in a Mexican household where “machismo” is emphasized. While patriarchy is embedded in cultures internationally, boys in latino cultures are raised to be “machistas” — providers and protectors that evoke pride in their masculinity and self reliance, according to “Machismo Literature Review,” published by Rochester Institute of Technology. Valenzuela’s dad didn’t show emotion, so neither could he, or so that’s what he perceived by his father’s archetype. This may explain why men are less likely to seek help for mental health issues than women, according to World Health Organization.

“The only time I was able to be emotional was when I was alone, and I spent a lot of time alone as a kid,” Valenzuela dismally recalls, reminiscent of his childhood. “When my dad would tell me to ‘stop being a sissy’ I knew I was going through something, but he didn’t explore what I was feeling.”

As Valenzuela grew into his adolescence, his mother’s worry about his quiet, distant behavior grew as well. She had him see a psychologist for some time as a teenager. Valenzuela says the approach didn’t work because it was forced upon him and felt he was just going through a “normal teenage phase.”

“There is definitely this idea of weakness around the idea of reaching out for psychological help,” Valenzuela says. “The last thing you want is for people to think you’re crazy. This is especially true for men. They want to be seen as manly, little do they know that they’re not crazy. They’re just going through things that other people go through but obviously just don’t know how to manage it.”

Miguel Douglas, nurse and former counselor at the Willow Rock Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Center in San Leandro, says the stigma of men’s mental health is a vicious cycle.

“Some men have a hard time expressing themselves because they have a fear of being judged as being less of a man or even homosexual, and that comes down to the big factor of men’s masculinity,” he reveals. “And that leaves that big dilemma of them not being able to express themselves when they face situations where it’s necessary.”

Valenzuela recalls a day when he was working out with his trainer, and although hesitant to do so, he expressed to him, “Dude I’ve been really stressing out, I actually feel like crying.” His trainer surprised him with his response, “If you want to cry, then cry. It’s okay to cry because that’s your own body telling you that you need to relieve all that stress. That’s your body detoxifying itself from whatever you’re going through in a healthy manner and that’s okay because we are human.” This moment helped Valenzuela accept that what he was feeling wasn’t wrong and changed his outlook on seeking psychological help if needed in the future.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates that 6 million men in America deal with depression in a given year. Statistics for men’s mental health may lack accuracy due to the unwillingness of men to admit psychological issues. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, younger men of color who reported daily feelings of depression or anxiety were less likely than their white male counterparts to take medication or talk to a mental health professional.

“Especially in … working class communities, young men are more likely to experience and be exposed to a lot by the age of ten,” Douglas says. “These young boys are walking around with a bank-load of experience at an age where they are still too immature to know how to piece together these experiences and tie them together with their feelings.”

Researchers at the Yale School of Medicine found that “repressor” personality is rooted in psychological experiences of childhood. It is reported that repressors not only mask their emotions but often are not even aware of their inner stress.

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, about one-in-four children in the United States spend some or even all of their early childhood in poverty. A study done by psychological scientists Gary Evans and Rochelle Cassells shows that boys who grew up in ethnic minority, impoverished, and/or crime-ridden communities showed signs of worse mental health in emerging adulthood. Distinctively, time spent in poverty was associated with higher levels of externalizing symptoms and learned helplessness by age seventeen.

Valenzuela believes he nearly escaped depression by realizing that his reluctance to express himself growing up stemmed not only from his father’s impassivity but his parents’ absence.

“My family was always working so there was no time to build the type of relationship where I could tell them whatever I was feeling,” says Valenzuela.

Douglas deduces that parents often reinforce gender stereotypes that encourage a harmful developmental process.

“The notion ‘boys will be boys’ is a thought process used as an excuse that allows parents to be okay with their sons acting out through aggressive behavior,” he says. “Seeing it as a norm takes away a wide range of disciplinary ways to mold and shape a young man’s mind and behavior, which affects them in the future”.

Valenzuela observed domestic violence in his home, which was dismissed and deemed normal due to the machismo ideology that lingered in his household. He was fortunate to learn from his father’s mistakes rather than mimic them. He searched for different outlets for his stress aside from violence and alcohol.

“I started going to raves a lot because it was an environment where I could just be myself, and of course drugs were involved,” Valenzuela admittingly says. “Maybe it was just at that point in time that my mind was in a stress-free environment and mindset, but it was much easier to see through the bad stuff.”

Valenzuela later realized that his substance abuse was just filling a void. He has learned how detrimental a lack of communication in a household can be, and credits it as a main contribution to men’s unwillingness to consider mental health support. He now has a more healthy approach to addressing his mental health concerns.

“Whenever I do get stressed I just keep busy, find things to do as simple as hanging out with my friends, going out, working more, and other things … that keeps my mind off of stressful things in my life,” he says. “I already know what to do and what not to do in the future with my children, because I lived it and I know how unhealthy it can be mentally.”