Without preparation I found myself in a dim room, encircled by lips mouthing disjointed words on the screens of smartphones. In the middle of the room, clear containers with flickering green neon lights inside them mesmerized me. The containers, it turns out, have a purpose. Within each of them are labels – words used to identify, divide, or stratify individuals.

Although it was unclear at first, I began to notice the words being mouthed were also labels. Many of them carry negative connotations such as “disgusting,” “terrorist,” “deplorable,” and “nasty.” The containers at the center of the room are lined up to form a wall, and performers on either side of the wall began to call out names of individuals on the other side of the wall. Each time louder and louder, but no one seemed to acknowledge them. The wall of labels continues its job of keeping people apart.

This performance, titled “Brainwash Machine”, was presented by Kinetech Arts at the Yerba Buena Center for Arts. Using evocative imagery it explores the implication of labels in modern day society. The labels used in the performance, although charged, have become familiar, everyday language in our current political state.

Organizing

In the same building, volunteers from 100 Days of Action are giving out information about their project. 100 Days of Action is a direct response to President Trump’s first 100 Day Plan. Educators, activists, and artists organized to provide a counter-narrative to President Trump’s plan in calendar form. Anybody inspired to act against President Trump’s narrative is invited to submit a proposal and have their idea featured in the 100 Days of Action’s online platform.

“We felt that gestures when done in communion can carry great meaning,” says Ingrid Rojas, project organizer for 100 Days of Action. “And in the wake of the assault of the rights of people in our communities, we wanted to stand together and provide gestures, and ask the community for gestures, that could help us craft a voice of unity, nuance, and acceptance.”

Artists of all kind are using this platform to display their concerns with the Trump administration, and finding interest in their work within their community. The individuals involved in 100 Days of Action have been present in various communities in the Bay Area, at protests, in areas affected by gentrification, and in places where people most marginalized by President Trump’s policies reside.

100 Days of Action features “Sloughing,” an unconventional performance from Raegan Truax where any menstruating woman can participate by simply bleeding onto plywood boards. Truax wants bring attention to quality health care and highlight the resistance from “nasty” women who stand against President Trump’s sexism. On Valentine’s day the project featured a special reading and open mic hosted by Julia Goodman and Michael Hall. The event encouraged the public to voice their concerns on love and politics by reading poems or sharing an image that inspired them.

One need not look only to projects like 100 Days of Action to see a surge of political art in the Bay Area; several artists are stirred to display their activism and political views in creative ways.

Political Art

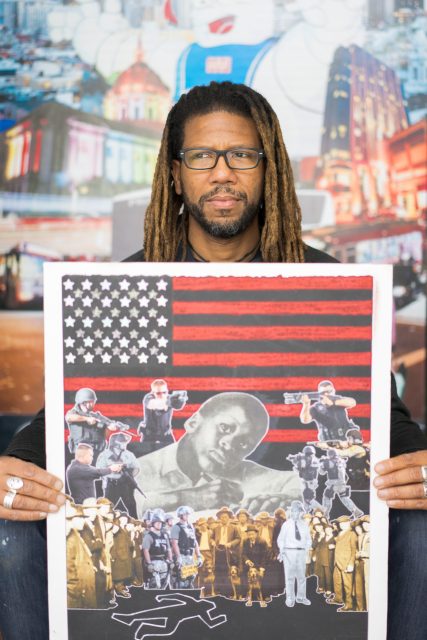

Over the past few weeks San Francisco based visual artist, Mark Harris, has been caught in a frenzy of media attention after complaints about his work resulted in his art being removed from a public exhibition. Still he’s been receptive to all requests for contact, and said he’s received a lot of encouraging and positive responses amid all the exposure.

Earlier this month he was asked to gather some of his work in observance of Black History Month for display at East Side High School in San Jose. Among the work chosen were pieces that brought attention to police violence with a call to “stop killer cops.” All of his paintings aligned with issues concerning modern day Black rights activism – topics that could be discussed during Black History Month. Unidentified individuals had expressed concern and discomfort over the subject of his work and requested they be removed; within hours of being displayed his work was taken down.

In the wake of 2014’s Ferguson protests and the shootings of unarmed Black men, Harris began to channel his anger into his work. Rather than producing abstract art in the form of acrylic paintings, he began to use more mixed media, and focused on the prevalent social issues driving the activism behind the Black Lives Matter movement.

“My work has changed because I want to challenge myself. I don’t want to do the same thing all the time. I get bored. Around the time of the Ferguson riots, like two and a half years ago, was a shift for me. It was the third shooting of an unarmed African American after Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant, which both really impacted me,”.

In both of these controversial cases, the results have frustrated activists who felt that there was little repercussion, if any, for the white men who shot Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant.

“I couldn’t just not do anything anymore, and I was angry. As an artist I had to learn how to channel that and how to use it in order to make a difference.”

Harris has not been deterred by the censorship he’s experienced. Currently, he’s working on a series of political stamps, some of which might not agree with all viewers since they candidly criticize President Trump and the current state of the U.S.

“I want to inspire people, and I want to make a difference. I think making political art is the best way to do it,” Harris says. “I do think a lot about maybe if I didn’t make work that wasn’t political I’d make more money, but this is the work that comes out of me and I like it. It’s fun, it’s challenging.”

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”5″ sortorder=”15,14,13″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_imagebrowser” ajax_pagination=”0″ order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]San Francisco State instructor of creative writing, Truong Tran, is another artist who is using his creative talents to produce political art. Tran is both a poet and a visual artist. He moves between the two mediums comfortably to express his creative vision. Tran feels inspired by the events happening around him, both on a national and a local level. He has worked on pieces that bring attention to the displacement of artists in San Francisco and the plight of being a marginalized person of color in the U.S. Tran says that now more than ever activism and art have to go hand-in-hand.

“I don’t feel that it’s that important for me to develop my career right now,” says Tran. “I feel that it’s more important for me to make art in response to this time; to use my art in a tangible way, to support the needs of my community.”

A common denominator in Tran’s pieces are the political thought behind his artistic process. To construct his visual art pieces, he uses materials he finds that are recyclable and reusable; a choice that he identifies as political because he strives to make his art accessible to all.

“I’m interested in everyone having the opportunity to access art.” Tran says. “I am concerned that art in this given time feels very much like it’s for the privileged.”

One of the plans of President Trump’s administration is to make budget cuts to federal agencies and increase the national defense budget. According to a report by The Hill, an American newspaper dedicated to covering politics, one of the agencies that he’s looking to eradicate entirely is the National Endowment for the Arts. The results of this act could make art even less viable and more exclusive to a small percentage of Americans who can afford access to museums, higher institutions, and spaces where art thrives.

“Artists are called upon to be fighters we fight for our own survival,” says Tran. “But we also fight to preserve the consciousness of the world around us.”

Last Christmas Tran held a fundraiser selling some of his art to support the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, and Kearny Street Workshop, an Asian American art organization in San Francisco. He wants to make the fundraiser an annual effort for the next four years in hopes of protecting the power of art both here in the city and abroad.