BAM!

The wrestler’s forearm slams into his opponent’s chest. Crashing to the ground, the wrestler knows this may be his only chance. He quickly turns and rushes over to the corner of the ring and begins climbing. Up to the top rope of the ring apron, the wrestler gazes out at the high school gym. Hundreds of excited faces stare back at him, the raucous crowd watches with anticipation. The wrestler feels two arms wrap around his waist and realizes his downed opponent has scaled the ring apron as well. Arching backwards, the opponent flips the wrestler over in a beautiful German suplex maneuver. The wrestler makes sure to land on his upper back and roll through onto the ring mat, avoiding his head. Finally, he grabs his skull as if it were injured and lays prone, grimacing in faux pain. Yes, the wrestler knows that wrestling is fake.

Wrestling is an age old form of entertainment. The art of staged fighting finds its roots in almost every culture. The masked men and women of Lucha Libre are well-known in Mexico, while America reminisces the strongmen of old carnivals that eventually became modern wrestling. While most are familiar with the lucrative World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), smaller indie wrestling promotions still exist all over the world.

These indie promotions hire wrestlers to travel everywhere, performing in any high school gym or bingo hall that will take them.

“When I started training in 2015 I didn’t know how many indie wrestling promotions there were,” Karl “The Big Effin’ Deal” Fredericks explains.

Karl, known as “The Big Effin’ Deal” in the wrestling world, is one of many touring wrestlers. A recent newcomer to the scene, Karl has gotten to see the recent explosion of indie wrestling first hand.

“I knew the worldwide, the WWE’s, the new Japan Pro Wrestling’s, the Ring of Honor’s, the bigger ones. I didn’t know I could go and travel as much as I have. As soon as I started wrestling it was a new world to me, and it was exciting because obviously this where I’ve made my name, where I’ve honed my craft.”

Often mistaken for a sporting event, it’s important to know just what wrestling entails. Akin to a theatre performance or a magic show, wrestling is a staged fight with the intention of telling a story. It has more in common with the movie Rocky than with the UFC.

Like a magician who never reveals their secret, wrestlers and fans are adamant that wrestling is real, in order to “protect the business,” a phrase that refers to treating wrestling like it’s real despite the common knowledge that it’s not. The wrestler, audience, and viewer at home are all participating in a form of exciting escapism. American screenwriter, director, producer, and comic book writer, Max Landis, shows it best in his mini-documentary Wrestling isn’t Wrestling.

“We need entertainment and we need it now,” asserts Landis.

“When you watch wrestling, that’s what you get. Wrestling is melodrama, wrestling is mythology, wrestling is action, wrestling is comic books. The only thing wrestling isn’t, is wrestling.”

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”18″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_thumbnails” override_thumbnail_settings=”0″ thumbnail_width=”240″ thumbnail_height=”160″ thumbnail_crop=”1″ images_per_page=”20″ number_of_columns=”0″ ajax_pagination=”0″ show_all_in_lightbox=”0″ use_imagebrowser_effect=”0″ show_slideshow_link=”1″ slideshow_link_text=”[Show slideshow]” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

THUD!

The wrestler’s opponent rolls over onto him, lift his leg and pinning the wrestler’s shoulders to the mat for a three count and the win. The referee slides into position and throws down his hand.

One!

“It was a German suplex from the top rope,” thinks the wrestler.

“It deserves at least a 2 count, make the other guy look strong, and make myself look resilient.”

The referee’s hand windmills around and hits the canvas gain.

Two!

As the referee brings his hand for the final count, the wrestler kicks his legs out, propelling his shoulders off the mat at the last second. The crowd let’s out a booming cry of ‘two!” in response. With his opponent grimacing in false shock and dismay, the wrestler can’t help but crack a smile. Now it’s time for his comeback.

Indie promotions aren’t new, but their surging popularity is. Almost two decades ago, WWE was the only place to get work done. Boasting over 2.5 million buys on just their four main Pay-Per-Views in 2001, the WWE was king.

Now wrestlers can find a dozen places to work in any area. Karl has worked for All Pro Wrestling, Pacific Northwest Wrestling, Fist Combat, and many more promotions in just the span of two years, and all in California.

Kirk White, the owner of local Bay Area wrestling promotion Big Time Wrestling remembers early on in American wrestling history.

“Back in 1996 there were probably fifteen people that were with WWE or WCW or NWA that had TV time that you could book. There weren’t nearly as many as you have now,” White reminiscences.

“Now there’s more wrestlers available. There’s more talent available.”

This doesn’t mean that wrestlers always have an easier time getting a job though.

“The wrestlers today aren’t as grateful for the bookings they get. The business has been brought up on respect, and I don’t think a lot of it goes on right now,” asserts White.

“If you’re not humbled, I have no use for you.”

This weight of self-image and responsibility is everything for a wrestler. They act almost like independent contractors, promoting themselves and selling their own merchandise wherever they wrestle. The more people they draw, the bigger a wrestler will get. That means they have to get the crowd on their side, whether they are a “good guy” or a “bad guy”.

“I spent the vast majority of my career wrestling as ‘baby-face’, as a good guy. September of last year was my heel turn when I became a bad guy,” Karl explains when asked about grabbing the crowd’s attention.

“A lot of it’s feel. If I kick a guy and the crowd loves it, I’ll probably kick him two or three more times,” admits Karl.

“Today I was the victim of a good handful of chops to the chest. He started lighting me up and the crowd was into it he so kept lighting me up. It’s that thing, pulling the emotion out of the crowd.”

KA-POW!

Throwing himself backwards, the wrestler bounces against the ropes, propelling himself forward and he slams his shoulder as his opponent falls backwards landing on his upper back. The timing creates the perfect illusion of collision, and the wrestler rebounds off the ropes again to repeat the process. Then the wrestling smoothly picks up, his opponent gives a slight hop to make the process go easier. Once on his shoulders, the wrestler turns and plants his opponent onto the ground, making sure to carry him the whole way down and level out his body, minimizing impact. Standing above his downed foe, the wrestler raises his hands to the crowd, allowing his stance to spurn boos and jeers from the audience around him. He smiles again, but this time wider and less subtle, doing his best to communicate his cocky persona.

It may seem odd to analyze how to entertain people, but the art of crowd control in a wrestling match is just as touch-and-go as the death defying flips and dives the wrestler’s take to tell their stories.

The Young Bucks, a Southern California tag-team made of up Matt and Nick Massie, have mastered this art in most countries around the world. Part of a team of indie wrestlers known as the Bullet Club, the Young Bucks have created a ring persona and merchandise system that has taken wrestling, and popular culture, by storm.

“We try to make it as much fun as possible,” explains Nick, known in wrestling as Nick Jackson.

“Today’s audience for anything entertainment wise has a short attention span, so we try to keep the fans attention with the ring style that we take part in.”

The Young Bucks have also done a good job keep fans attention on their merchandise. By selling their shirts at Hot Topic, the Young Bucks, and Bullet Club, have outsold all WWE’s merchandise sold at Hot Topic as well. They also created a mockumentary-style Youtube series called “Being the Elite” that breaks one hundred thousand views most episodes.

“The most rewarding part is watching a silly idea get over with the audience. You can see and feel it happening,” admits Matt when talking about “Being the Elite” and connecting with the crowd.

This vein of success makes waves in what is otherwise seen a rather underground industry. Karl Fredericks sees stories like the Young Bucks as rugs of a ladder he can climb now.

“The thing is you can make six figures on the indies and it’s crazy. It reminds me of a lot of rappers. You look at rappers today, they’re not signing record deals,” Karl elaborates.

“They’re like, ‘I’ll put my money for the tour,’ and they’re getting a lot back. The Young Bucks are in Hot Topic, and that money is going to the The [Young] Bucks, rather than the WWE shirts that are going back to the corporation. On the indies there are just so many places to work. You get that buzz and you can work anywhere.”

Karl knows he still has way to go, but he’s excited as his prospects.

“I’m just a kid trying to wrestle. I’m still driving myself everywhere but I love professional wrestling, and I want to give my life to this. It is a very good time to be a professional wrestler.”

The hardships of the tour life can’t be understated though. While the Young Bucks are living the independent wrestlers dream, it takes a toll. Between June and October of this year, the Young Bucks wrestled in North Carolina, England, Scotland, Georgia, Nevada, and Pennsylvania.

“That’s the hardest part about what we do, balancing life. ” a fried Matt admits.

“I’m never not tired. I just try to be around as much as I can for my family, but also try to be on the road enough for my fans. I’ll never get it perfect, but I’ll keep trying. Also, lots of coffee – addiction levels. I’m jittery as we speak.”

A wrestler can make six figure on the indies, but that cost can’t always be counted in dollars. It is a raw passion that keeps these athletes going. The love of the sport melded with the love of art. Karl knows the hardships. He drives six hours to Daly City and six hours back to his home in Reno at 11 p.m. every time he wrestled for APW, his main wrestling promotion.

“Everything we do is so physical, every move has meaning,” asserts Karl.

“You can’t fake throwing your body into the ground. We’re one-take stunt actors, and it all hurts. If you’re good everything hurts, just like any other sport.”

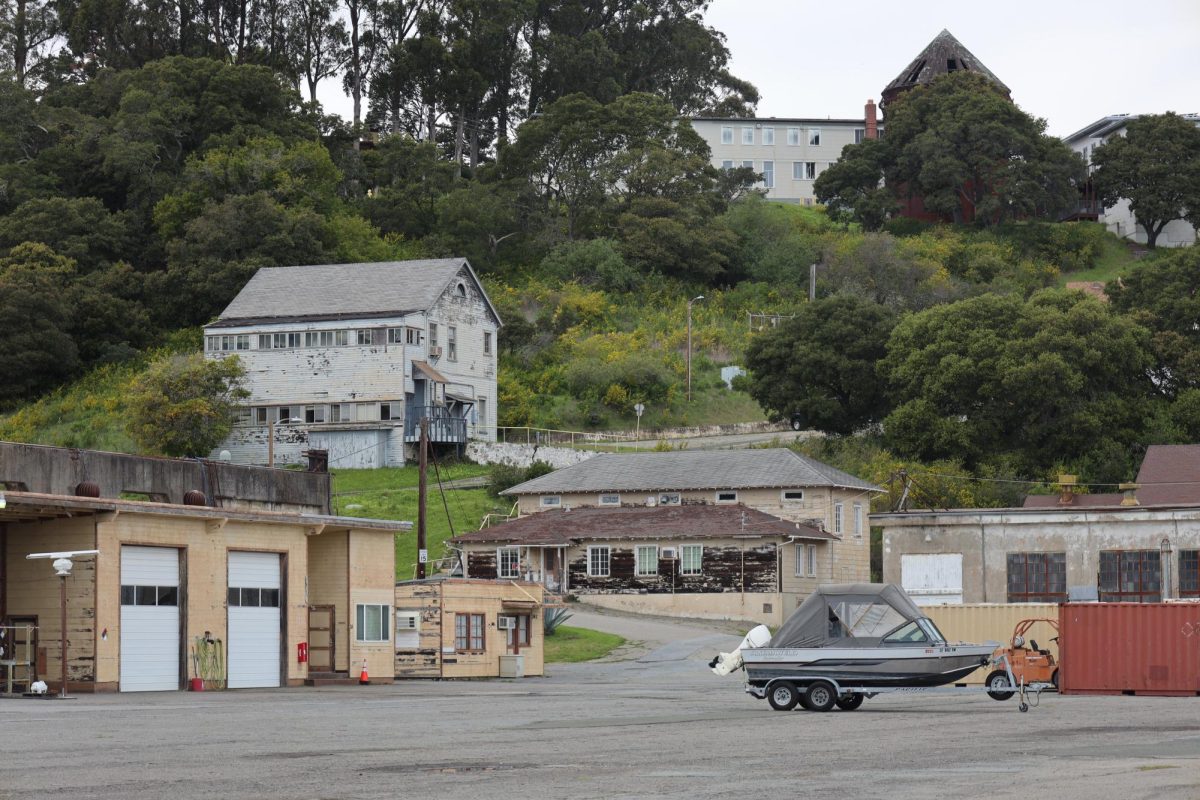

The beauty of indie wrestling is the accessibility. If someone has interest, there is an outlet. On November 10, APW is taking over the Cow Palace for a larger show. Kirk White’s Big Time Wrestling (BTW) company meets monthly in the East Bay to entertain hundreds of people. New Japan Pro Wrestling, WhatCulture Pro Wrestling, and Ring of Honor televise what matches they can, hoping to gain traction with new generations of fans. It’s the passion of the wrestlers that throw themselves around though that really drive the point home.

“Go to an indie show, it’s a variety show,” Karl implores.

“It’s The Muppet Show, it’s Saturday Night Live. You get the comedy. You get the good guys, the bad guys. There’s something for everybody. It’s fun.”

CRUNCH!

The wrestler swings his legs out, flipping himself from a standing position. As he careens with ground though, his opponent is missing. Slamming into the mat, he’s roughly dragged back to his feet by his opponent. The wrestler’s head is positioned between the hooked arm of his opponent and driven down toward the ground. The crook of the arm is placed carefully so the wrestler’s skull doesn’t spike the mat, but his head is still rattled a bit. Then the wrestler is flipped over, and his shoulders are again pinned to the floor. This time though, the wrestler doesn’t kick his legs out. The wrestler is losing tonight. He lays back and gasps a bit for air as the third hand from the referee comes down.

The match ends.

The wrestler has another match with someone new tomorrow night, and all stories must come to an end for now.