For two decades, from the mid 1950s to 1970s, a dozen missiles sat, primed and ready, just a few miles North of San Francisco’s city limits. They lay in wait in a highly secure military base, armed with enough power to blow a plane and its potential nuclear payload out of the sky. Today, U.S. Army site SF-88, which once housed the fearsome weapons, now belongs to the National Park Service. The site is open to visitors who want to see, hear, and feel the vestiges of military technology meant to keep San Francisco protected from an atomic attack.

At the height of the Cold War, as the threat of nuclear warfare crept deep into the American psyche, the U.S. Army began an ambitious infrastructure program to act as a failsafe against the threat of a Soviet attack. Named after the Greek goddess of victory, approximately three hundred Nike missile sites were built across the United States—all strategically placed around high-density population centers.

As part of the San Francisco Defense Area, the Army built a dozen Nike missile sites across the Bay Area, including two sites with launch areas within city limits. These were Fort Funston, which sits along the coast about a mile West of San Francisco State University’s campus, and Fort Winfield Scott, part of the Presidio of San Francisco. During the Cold War, both were armed with Nike missiles. Today, both are part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

SF-88 is the only fully restored Nike missile site in the United States, according to the National Park Service. The site was constructed in 1954. It coincided with the deployment of the Nike Ajax, the first guided surface-to-air missile in the world. SF-88 remained operational until 1974, when the Nike program was terminated. By then, changes in missile systems and technology had made Nike sites obsolete.

President Richard Nixon created Golden Gate National Recreation Area in 1972. The Army then began transferring ownership of its land surrounding San Francisco to the National Park Service. The largest concentration of these holdings was in San Francisco’s Presidio and the Marin Headlands.

“There was an Army colonel that was part of that transition team, between the Army and the park service,” said Greg Brown, a veteran of the Nike missile program and docent at the site.

Col. Milton “Bud” Halsey served in the Korean and Vietnam wars. The son of an Army officer, Halsey became the executive director of the Fort Point and Presidio Historical Association. After he passed away in 2001, his remains were interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

“He lived in the Bay Area and he had the vision of making a historic site, but at the time he had no equipment—all the equipment had been taken away by the Army,” Brown said. “He had friends in the Army and they had this old equipment and they said, ‘Hey, we’ll put it on a truck and bring it over.’”

Halsey successfully used leftover hardware from other Nike missile sites to fully restore SF-88. While the park service oversaw the project, Halsey and volunteers from the Nike Historical Society arranged to provide power to the equipment and restore it to operational order. Today, site volunteers help answer questions from visitors and demonstrate how some of the equipment functions.

“A lot of this wouldn’t have happened without the volunteers,” said Brown.

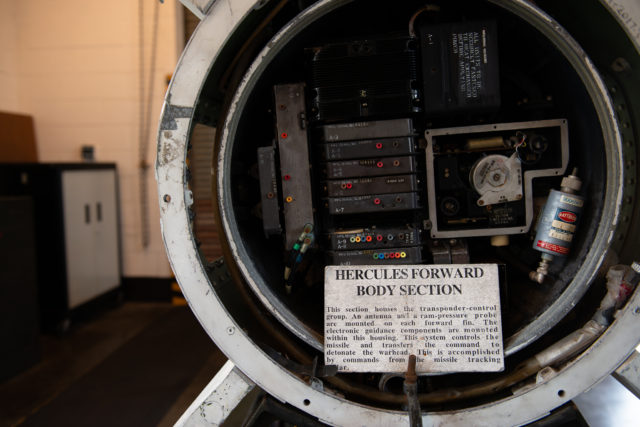

In 1959, just five years after the construction of SF-88, the Army deployed the Nike Hercules missile. It quickly surpassed the Ajax with its improved capabilities, including the ability to be fitted with a nuclear warhead. It was heavier, faster and had a greater range—about triple the approximate thirty-mile range of the Ajax. The missiles on display today at SF-88 are the Nike Hercules missiles.

Nike sites were meant as a last resort against a potential bombing run by Soviet aircraft. If neither Air Force nor Navy defenses could remove the plane from the sky, Nike sites had to be prepared to launch a surface-to-air missile that would destroy the aircraft before it could deliver its payload.

Jerry Feight, a veteran with the Air Force and a Nike Historical Society volunteer, worked with missile systems for much of his time in the military. He said that Nike missiles were meant to destroy not only an aircraft and its crew, but also anything else that might considered a threat.

Feight described the potential power of a Hercules missile to a group of visitors: “If it had the big boy, two and a half times, at least, the power of Hiroshima.”

According to the National Park Service, the Nike program was the most expensive missile system ever deployed.

Adjusted for inflation, Feight said, the estimated cost to build the Nike program today would be upwards of six trillion dollars.

“You learn from your past,” said Alec Gyorfi, Nike veteran and Nike Historical Society volunteer. “We overspent the Russians.”

In addition to the financial cost, the program required a substantial commitment of human effort. Firing a missile was an involved process. The crew would use machinery to move the missile into position for launch and the booster would propel the missile into the air. A radar operator would then lock onto a target, after which a computer would guide the missile to its destination. The entire process would largely be dependent on the reflexes of not only the crew at the missile site, but also the crew of the hostile aircraft.

Gordon Lunn was just out of college when he first worked at a Nike missile site.

“I characterize it as being 99 percent boredom and one percent panic,” Lunn said. “You had to be trained to the highest level possible at all times.”

Lunn, who retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel, was an officer when he worked in the Nike program. He described a time when a flock of Canada geese almost prompted his site to fire a missile.

“Adrenaline was pretty high that night,” Lunn said. “We didn’t know what it was.”

Lunn added that he believed if there had been any kind of confrontation with a hostile aircraft, the Nike site would be faster to respond. He believed this even in the face of doubt from others. “My response to them is: I think we are better than they are and we’re going to get them before they get us.”

Crewmen conducted daily maintenance checks and were equipped with gas masks and radiation meters to increase their preparedness in the event of an attack. They were stationed near the site to be ready at a moment’s notice and often had to work twenty-four hour shifts—sometimes for days on end. Most were young men, some just out of high school.

Brown worked as both a radar and missile crewman. “Most of us were seventeen, eighteen, nineteen years old,” he said. “There’s a lot of things you don’t think about until you’re older. Like pushing the button. That’s why they like young people to do that. Because they don’t think about the consequences too much.”

Training for each of the positions at the sites was specialized. For instance, maintenance operators did not necessarily know how to do the job of radar operators.

“When I was in Chicago I decided I wanted to do a little cross-training,” said Ed Thelen, a veteran of the Nike program and a volunteer of the Nike Historical Society. “So, I walked into the launch area and I promptly got thrown out on my butt.”

Thelen joined after college, when the Nike program was still in its infancy. He felt that some of the crewmen were not as responsible as he thought he was. He said the Army got its act together and training improved.

Readiness drills were common at Nike sites as well as exercises to test whether crewmen followed protocol. Sites competed to see which crew could be at their stations and performing their tasks faster.

In 1957, the Soviet Union tested its R-7 missile—the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile capable of delivering a nuclear warhead. With a far greater range than other missile systems at the time, the creation of ICBMs became an important technological advancement in modern warfare. They continue to remain in active use by several countries across the world.

“In the first Cold War, I think there was more awareness of the public that we have a potentially dangerous situation,” Lunn said. “Where today we have the same situation but the awareness is not there.”

During their deployment, Nike missile sites, while inaccessible to the public, were still meant to be highly visible. The reason for this was twofold: residents protected by Nike sites would understand the role that they served and potential aggressors would be intimidated by the open presence of the weapons.

This sort of tactic is not just a relic of the past.“We are in a second Cold War,” Lunn said. “Some of the players are the same: the Russians and the Chinese. But there are some rogue nations like Iran and North Korea.”

In late July, Reuters reported that a senior U.S. official said U.S. spy satellites showed what may be new production of ICBMs in North Korea. A little more than two months before that article was published, the New York Times reported that a group of weapons researchers had reviewed satellite photos of a stretch of desert in Iran and concluded a missile testing facility might be operating there—one expert concluded that such a facility might one day be capable of producing ICBMs.

“People tend to think about the Cold War as being over. We compartmentalize it,” said Jessica Elkind, associate professor of history at SF State. “It’s debatable whether the Cold War really truly ever ended.”

Elkind characterized the Cold War as being a time when larger governments would aid—whether financially, militarily, or otherwise—a smaller country to serve its own goals. Another tactic, she said, was the effort to project military might.

According to North American Aerospace Defense Command, two F-22 fighter jets intercepted two Russian bombers south of the Aleutian islands in early September. While the bombers did not enter U.S. airspace, their close presence to the Alaskan border prompted the two F-22 fighters to follow and maintain visual and radio contact with them.

Elkind cited the threat of non-state actors, such as terrorist groups, as being a more significant threat today than during the Cold War. Cybersecurity, she added, is a serious concern today because of new technology.

“There are technologies that people have access to now that can be much more destructive than in the past,” Elkind said.

![[Video] No Trump, No Feds, No MAGA; San Francisco says "No Kings!"](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-28-165913-1200x675.png)

![[Video] Gators Give Heartfelt Donations to Blood Drive](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/bloodstill2-1-1200x675.png)