Jose Garcia is living the American Dream.

The twenty-one-year-old Bakersfield, California resident’s family immigrated to America from Mexico when he was eleven. He grew up getting into trouble, getting kicked out of school and hanging out with the wrong crowd. Though he came from a broken family, he and his mom made ends meet by working in the fields of California’s Central Valley.

But not anymore.

A look at Jose’s Instagram page has him showing off his gold watch, going to corporate events, and posing with sports cars. He’s achieved this flashy lifestyle by joining a company called PHP, or People Helping People.

It, like many other companies in the United States, uses a business model called multi-level marketing, or MLM.

This business model has driven multi-million dollar companies such as Herbalife, Amway, and Cutco to their levels of success and prominence.

PHP sells life insurance, and Jose brings people onto his team to do the same.

“I’m not making millions yet, but I do have the chance to do it,” he explains. “You can make residual income, so everything adds up.”

Many Mexican immigrants like himself and his family dream of coming to America, making a lot of money, buying a nice truck, and building a nice house back home. Jose will tell you about the new Chevy Silverado that he bought, the great people he’s working with, and the land he just purchased in Mexico to build a house for his mom. Just like any American Dream success story, he’s worked hard for it.

“How successful you are depends on how hard you work. It’s capitalism, man,” he says. “Whoever works hard gets paid out. You grind, or you don’t eat.”

The more people Jose brings into the company, the higher commission he will get on his sales. That’s how to make the real money in multi-level marketing. Right now, he has seventy-five people on his team. Seventy-five is a lot of people, but it still seems doable, right? Jose reached that level in just two years. Surely, with hard work and dedication, success (i.e. big bucks) can be had through this side job with a minimal investment.

This is the pitch common to nearly all multi-level marketing businesses: Make some sales, recruit some more people just as you were recruited, and the money will start flowing in. Easy. Anyone can do it. Sign up now. It’s a pitch that sounds particularly appealing to the economically vulnerable: Immigrants, single moms, and college students. A 2018 study by AARP shows that 18-25 year olds joined MLMs more often than any other age demographic.

The problem appears when you start doing the math.

If, to reach Jose’s level of success, a prospective distributor would need to recruit seventy-five people, then all of those people would need to build their own structure of seventy-five, and so forth.

After five iterations of this, we reach two billion people.

Though PHP is growing, it is almost guaranteed that it won’t grow that big. Most who join won’t achieve the success they were promised. According to one study conducted in 2011 and published on the Federal Trade Commission’s website, ninety-nine percent of participants in most MLM’s don’t make money. Like Jose said, it’s capitalism. If you don’t work hard, you don’t eat.

That’s just a lot of people not eating.

Stacie Bosley, assistant professor of economics at Hamline University in St Paul, Minnesota, is one of the only economists in the country who studies multi-level marketing companies, which sometimes identify themselves with other names like network marketing, affiliate marketing, or direct sales.

“Direct sales,” according to Bosley, “is the umbrella term that includes all companies that utilize a distributor network to distribute their goods and services.”

Think door-to-door salesmen. Bosley became interested in MLMs when some of her friends and family became involved with direct selling companies that emphasized recruiting rather than retail sales. Many of them lost a lot of money, including retirement savings.

This focus on recruitment is what differentiates MLMs from direct sales. While direct sales consist of product sales without an online or physical retail store, MLMs grow and build their membership from recruitment.

MLMs incentivize members to recruit by offering commissions on sales made by anyone on their “team,” and by anyone recruited further by those members. This chain of recruits is called the downline, and the theoretically exponential size of this downline is why MLMs seem so appealing, especially for those wishing to generate a passive income.

If you draw this business model out on paper, you will find that you’ve drawn a pyramid; one in which all the money moves upward towards the top.

That’s why there’s another name for this business model: a pyramid scheme.

Pyramid schemes are illegal. While there is no federal law that strictly defines what a pyramid scheme is, there is a practical definition established by case law.

According to the FTC’s website, a company is a pyramid scheme if they “promise consumers or investors large profits based primarily on recruiting others to join their program, not based on profits from any real investment or real sale of goods to the public.”

Multi-level marketing companies avoid the pyramid scheme label by offering products and services. As long as a company can demonstrate that all involved make most of their revenue from sales of products rather than from recruiting, then they can avoid the pyramid label—and prosecution.

“Multi-level marketing has the veneer of a product or service,” continues Bosley, “but the fundamental activities remain: pay to participate, recruit other people to do the same, and you will ultimately be rewarded with greater payment.”

The people that are successful are often those who can get in first. For the vast majority who join, however, getting to the top is a much higher climb. Usually though, they don’t see it that way because it’s often advertised as an easy side gig.

Carlo Padula is re-reading Dante’s Inferno. It sits on the desk of his office in San Francisco State’s Italian studies department. As he describes his time working in an MLM, he picks it up. “I was in the Inferno. I was in hell.”

The sixty-two-year-old professor had joined a multi-level marketing company called Star Services International for two years when he was still living in Italy. A friend of his had told him that he had come across a good opportunity to make money without working. Though he was doing alright running his gardening store, he figured the opportunity couldn’t hurt.

“I lost money—a lot of money,” he says, shaking his head. “I invested a thousand dollars a year, and I lost everything. Everything.”

Star Services International, much like PHP, sold insurance policies. Carlo said that initially, he fell in love with the theory.

“The theory is perfect, but to apply the theory into practice is insane,” he explains. “They present it as easy and that you can make money without leaving your job. But it’s not true. It’s a job, a twenty-four-hour job sometimes.”

After two years in the company, Carlo had lost money. “My structure crumbled after one year,” he admits, “because I didn’t want to push people to do something that was not correct. Telling them to go to their grandmother and sell her the product? That’s her retirement.”

To be successful, he had to be deceptive. He knew what working for the company involved and how little money there was in it. He knew that the product was not something for everyone. If he could convince people he cared about to join but they didn’t do well, he would have to let them bleed out and find someone new.

“You have to cut heads,” he explains. “If your structure is dying, then you just start another structure. You are not caring for the people who are losing their money and leaving their jobs.” He reflects for a moment. “When I realized this, for me I have some principles that are higher. A friend is a friend, not because they can make you money.”

Carlo said he is thankful that he was able to preserve his relationships over the job. He knew other people that didn’t fair the same. “People get divorced, it’s broken friendships,” he says. “The first ten people are usually people you sell the product to, and those people are usually your friends and your family. You tell them that it’s because you love them.”

When Jose first joined PHP, he wanted to tell everyone about it. When he shared the opportunity with his friends in their group chat, one of them replied that it was a scam. Jose didn’t like that very much.

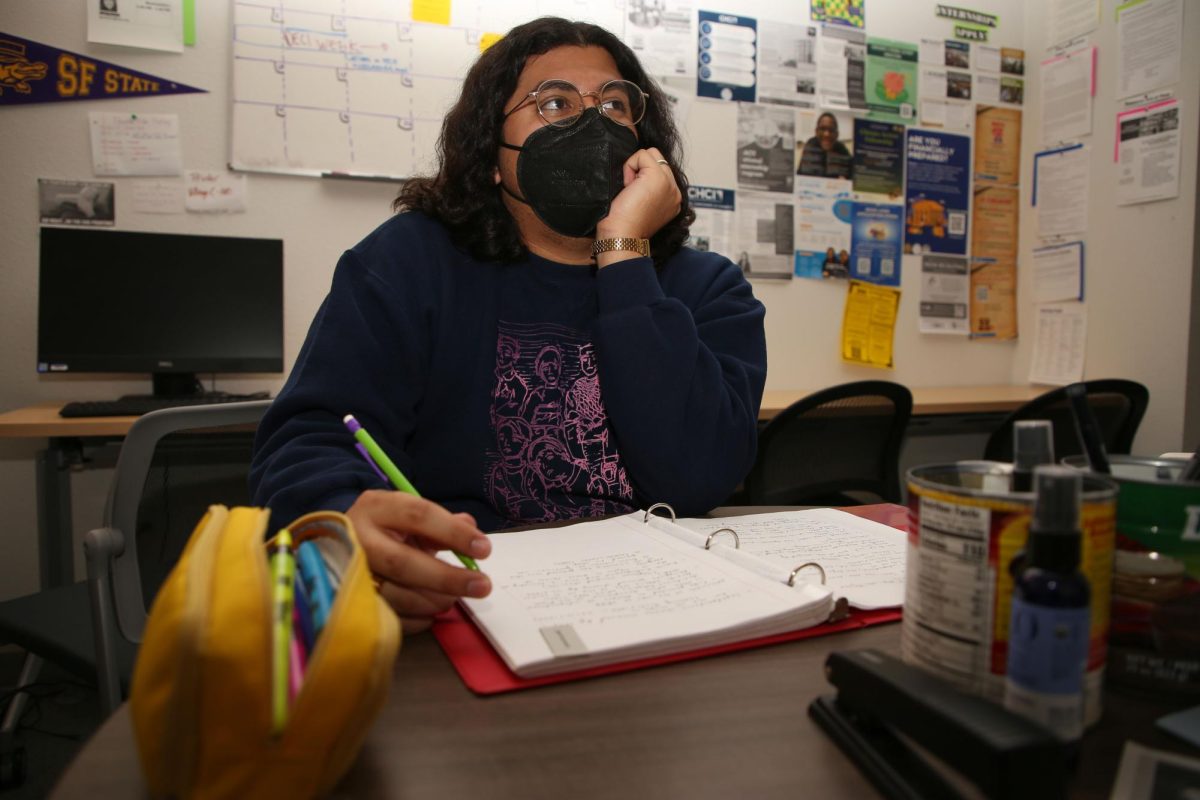

“He called me a hater,” Amaris Maestas explains. “Now to this very day he’s shaming me about how ‘oh, you can’t support your family, you can’t do this, you don’t got shit up north…’ shit after shit after shit.”

Amaris, a twenty-year-old business major at SFSU, had encountered the company before. While a student in Bakersfield, she had gone to one of their meetings thinking it was a job interview for a normal company. The meeting took place in a small, nondescript office building. In a room that was set up more like a presentation than a job interview, a young man was boasting to two young women about how he was going to upgrade his BMW.

“As soon as I walked in the door, I knew exactly what was going on,” Maestas says, slapping her hand on the table. She already knew about the MLM business model and was not a fan. She left, telling the friend she had brought that they had walked into a pyramid scheme. When Jose told her friend group about it, she said the same thing.

Though they had been friends for two years, this disagreement ruined that. Jose saw Amaris’ attitude as the result of ignorance, while Amaris saw Jose’s as the result of brainwashing. They didn’t see each other for a while, until Amaris and her mom were at the dollar store and she saw Jose and a business partner in suits handing out fliers.

“Yeah, I mean I talked to everybody,” explains Jose. Jose says that Amaris’ attitude was frustrating to him because he saw it as a way to build people up by offering them an opportunity. “When somebody is telling us that the company’s fake, it doesn’t work, or something like that, I don’t like it,” he says. “You’re stopping someone from doing something that they want to do. Why stop them from doing just because you don’t see yourself doing it?”

In her hometown of Bakersfield, Amaris says MLMs are common because the population is the perfect target. Amaris, who describes herself as light skinned Mexican, says that there are a lot of poor Latino people in her community. “Most of the white people there know this is not for them, but the Mexicans, this is their target. Mexican people and low-income students.”

MLMs usually focus their attention on “affinity communities,” valuable because of their tight knit relationships and high social interactions. Immigrant neighborhoods, churches, and college campuses provide the perfect petri dishes to spread into.

One company, Vemma Nutrition Company, focused its attention specifically on college students.

When Luis Contreras was invited to his friend Alex’s house in 2014, she wouldn’t tell him what it was for.

It was his first year at Chabot College in Hayward, California. He and Alex had grown close only recently. When he got to her house, he found that he wasn’t the only one she invited over. A group of strangers all found themselves in her living room. They were all hanging out and making small talk, when a couple of them asked the group if they wanted to try some drinks. They went into the kitchen and brought out cans of an energy drink called Vemma Verve.

“They tried to be slick about it,” says Luis. “That was their way to try and leave an impression. It was their way to say, ‘Hey—this is a good drink. If you guys like it then you should be a part of it.’”

They began talking about the drinks and the company, Vemma. They told the group that they could make a lot of money, and that eventually, they could even get a Mercedes. After watching some flashy music videos showing the Vemma Lifestyle, they said that all you had to do was sign up, and they would send you cases of the drink to sell at a retail price.

While Luis was skeptical, he went to two more meetings. After all, it was his friend that had invited him and he trusted her.

At the third meeting, things got weird. A guy who was higher up in the company explained how they would pay five dollars a day for the product, and that they would start off at the bottom. But, if they stuck with it, they could make a lot of money and the company would give them a car. “He kept saying, ‘you guys can be the next mega superstars, you could be the next big thing.’”

At that point, Luis had done his own research and had talked to other friends of Alex’s who were also skeptical. He told her it wasn’t for him, and she said that was okay. Then he tried convincing her that she should leave, too. That’s when she got defensive. Luis remembers her saying, “This company is my passion, this is my role. I wanna become successful, and I’m not going to let somebody talk to me like that and get in my way.”

That was the last time he saw her.

The now twenty-three-year-old Luis, who transferred to SFSU, doesn’t know what happened to Alex after that. Vemma, however, didn’t go unpunished for it’s aggressive recruiting of college students.

In 2016, the FTC responded to complaints by parents whose kids were telling them they were going to drop out because they found something better. The company was fined $238 million for operating an unlawful pyramid scheme and misrepresenting income claims. They were also ordered to restructure their company and change their business practices.

Though they complied, the changes to their business were minimal. Vemma still sells energy drinks and health products and still uses a multi-level marketing structure

The Vemma Case is only one of a handful of cases against MLMs successfully prosecuted by the FTC since 1979. That year is important because in 1979, the FTC fought a case against one of the biggest MLMs at that time and today: Amway.

Douglas Brooks is an attorney, consumer advocate, and legal expert on MLM’s. In the Netflix documentary, Betting on Zero, he represented a group of mostly undocumented Latino immigrants who had lost money in becoming distributors for Herbalife. He explains that the 1979 Amway case shaped the legal environment that allowed MLMs to grow to the level of prominence they hold today.

“Prior to the Amway decision,” Brooks explains, “it was clear that if the compensation plan allowed people to make a payment for the right to receive a payment when new people joined the business, it was a pyramid scheme.”

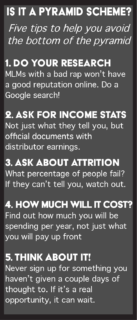

The Amway decision determined that as long as the company could show that it has rules, then it can be protected. The problem with this, however, is that it is very difficult for the FTC to prove whether or not these rules are being followed because MLMs are not required to provide accurate information about distributor income and attrition rates—in other words, they don’t have to say how much people make and how often they fail.

“The confusion is by design,” said Brooks. “They make these plans so complicated and confusing so that the person who’s just joining really can’t understand. Unless you have someone who’s had some experience sit down and explain it to you, you’re not going to understand it. And if you did understand it you’d probably run away from it.”

This means that it’s not only difficult for the FTC to prosecute these companies, but it’s also hard for consumers to decide whether or not they’re signing up for a scam. “If you’re a prospective distributor and you want to find out if the company is a legitimate business or a pyramid scheme… how are you going to determine if that is really happening? There’s really no way for you to do that.”

Whether or not MLMs like Vemma are pyramid schemes is important, but for Brooks, it isn’t the only concerning feature of the industry. For regular franchisors, like McDonalds for instance, they are required to make sure that franchisees have the ability to be successful. They aren’t allowed to let a new McDonalds open right next to the old one if it means that old one will go out of business.

MLMs, however, encourage the opposite. As a distributor, you are encouraged to recruit. Those new distributors are your own competition, making the prospect of actually making money from retail sales unlikely.

“Regardless of if something meets someone’s definition of a pyramid scheme, there remains the issue of if these are viable businesses.” Brooks emphasizes. “How are we going to know if the industry doesn’t have to disclose even basic information about how their distributors are performing?”

Multi level marketing isn’t going away any time soon. This means that those of us who are starving, debt-ridden students have to be careful when we find ourselves in fishy meetings and offered business opportunities by friends and family. The business model is a caricature of inequality—the wealth of the many moves up and into the pockets of the few. But who knows? Maybe you could be successful. That’s why Jose works hard to bring people into his company.

“What if they could come into the company and do something great?” said Jose.

He’s not wrong. You could be a part of the successful one percent, maybe even one of the wildly successful fraction of that number.

Maybe the next time you want to buy a lottery ticket, just join an MLM instead.