A Reflection on Body Image

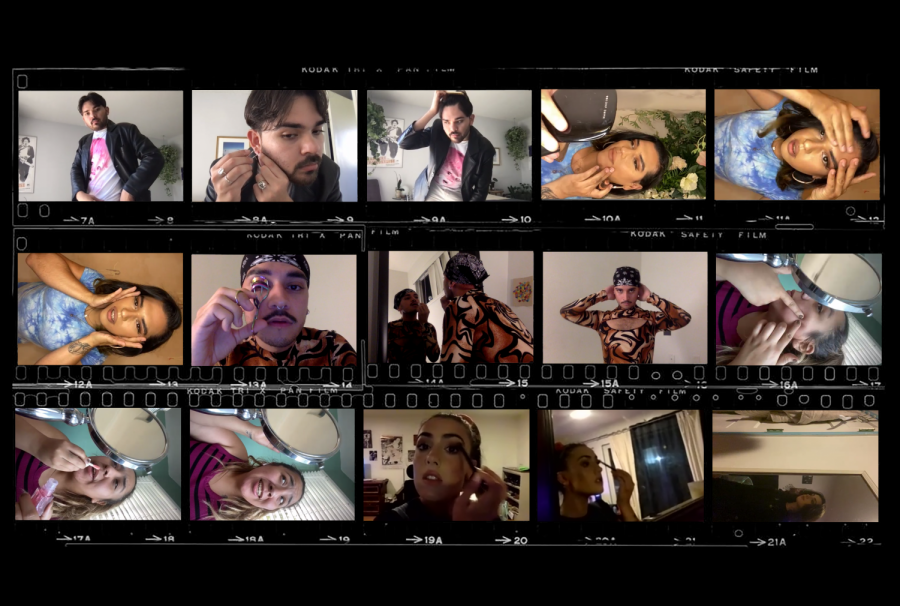

Collage of Erica Gray, Valentia Aragon, Christina Hernandez, Juilo Cesar Tello, Michael Anthony Hall (Paris Galarza / Xpress Magazine)

The following article mentions an experience of disordered eating.

The mirror feels like a necessity. It affirms if a garment fits well. It verifies that there is no lipstick stain. Over time, it harbors a relationship with a reflected self.

At its best, the mirror is a pep talk. At its worst, it reflects negative self-talk.

A research study, titled A narrative review on clinical and research applications of the Mirror Paradigm: body image, psychopathology, and attachment used The Mirror Paradigm (MP) to place participants in front of the mirror, asking them reflective questions to describe what they see and how they see it.

The study revealed mirrors make people vulnerable to the internalizations of external influences that shaped their self-perception, making correlations between eating disorders, body image and intimate feelings.

Mirrors encourage participants to consider the multiple dimensions of the self: self as seen and self as felt.

When a person looks into a mirror they see a reflection staring back and that image becomes interpreted as the real self, but if that mirror crumbles, the self will remain steady — thoughts, feelings and beliefs all standing.

There’s this fantasy

Michael Anthony Hall is a 22-year-old writer and San Francisco State University alumnus. At the beginning of Hall’s freshman year of college, he exercised more, ate less and lost weight, but wasn’t happy.

“I was working a lot and not prioritizing my health,” said Hall. “I feel like in the queer community, especially when you’re young, you want to fill these expectations just to fit in, to find community.”

In his late teen years, Hall began feeling hypercritical of his body.

“I personally feel the pressure because there’s this fantasy of this attainability of ‘I need to work out more, I need to look and feel a certain way,’” said Hall.

He grew up in a house full of mirrors and being surrounded by them made them become visual validations for Hall’s emotions.

Hall still likes mirrors, but mirrors sometimes feel exorbitant for they not only reflect adoration for his body but magnify hypercritical internal monologues.

“Now I’ve kind of maneuvered through (criticizing my body), I love my body. I love what my body does for me,” said Hall. “And, you know, confidence comes from within.”

A lot of work to do

One day in Erica Gray’s twenties, she decided to go out for a burger. She called up her best friend and they both drove down for lunch. As soon as they finished, Gray returned home struck by the guilt of self-resolution.

She entered her house crying and confessed to her family, “I ate a burger.” Gray began to have a mental breakdown, while her family approached her with open arms. She embraced rounds of hugs from her family, but couldn’t stop crying.

Gray’s older brother, Lenny, stopped her tears. “Stop crying,” he said. Lenny looked her in the eyes and said, “Congratulations, you ate a burger. You think you made some huge milestone or something? No, you have a lot of work to do.”

Shortly before eating the burger, Gray had received a second anorexia and body dysmorphia diagnosis — the first being at 15 years old.

“I was shocked because no one really talked about that,” said Gray. “I remember when my doctor told me, ‘You have an eating disorder,’ I was pissed. Like, bullshit, I don’t have an eating disorder.”

Gray was first in denial until she stepped on the scale and read 85 pounds, but in front of the mirror, she saw a different image.

The mirror reflected what her brain didn’t like about herself. Her body dysmorphia drew attention to her arms and legs. Her eating disorder became a voice that’d congratulate her whenever she’d lose another pound.

For a while, Gray listened. She’d let the voice of her disorder speak over her own. She’d work on developing better eating habits, but she saw grand results once she began to build her self-esteem and recognized her self-worth.

Gray thanks her brother who, in large part, helped her through her recovery process.

“My brother would say, ‘I understand everything you’re going through. Someone telling you to eat is like someone telling me to stop drinking,’” said Gray. “He helped me through a lot with tough love.”

Gray knows recovery is different for everyone. “Some people need to hit rock bottom, whatever that may be. Tough love was what helped me in the long run.”

Before all that love

Julio Cesar Tello started bar-hopping with his friends right after high school and watched handsome strangers approach them.

“(My friends) were skinny, beautiful, and I felt like that’s one of the things I had to be to get that attention as well,” said Tello.

He craved offers for a complimentary drink or an innocent kiss that could lead to love.

“I didn’t like how I looked,” said Tello. He believed this inhibited him from seeing his self-worth. So, after graduating high school, Tello lost 70 pounds.

“I looked skinny and I felt skinny, but when I would look in the mirror it looked like I was still looking at the person I was in middle school,” said Tello. “The issues never went away.”

Sometime after Tello lost weight, his self-image changed. He describes it as “a 180, with losing weight came so much confidence.”

He’s experienced both sides now, from feeling like he wasn’t able to attract people to feeling privileged after receiving compliments.

Tello now has a love-hate relationship with mirrors, “Mirrors have seen me transform throughout my life and I have seen myself transform through mirrors, but I hate it because it made me look at my insecurities every day and made me develop even more insecurities.”

Only one way to find out

Valentina Aragon was eager to move to San Francisco in her late twenties. As soon as she obtained an associate degree, she transferred to San Francisco State University and received a bachelor’s degree in psychology.

Aragon soon began applying her research skills into her personal life.

“Through my journey as a trans female, I’ve done a lot of observational research,” said Aragon.

“I found cis women with defined jawlines and big noses. I found women with smaller breasts, flat chests, with bellies, and big butts or no butts. I found all sorts of women who weren’t born with uterus or ovaries, but they were born with very developed feminine bodies and non-developed feminine bodies.”

It led her to become hypervigilant about the way clothes adorned the body.

She enjoys wearing loose dresses that fall just before the knee. She always has a trusty denim jacket for San Francisco’s notorious fog, but not every garment comes as easy to wear.

“Pants go with having to be uncomfortable and it affects the quality of your life,” said Aragon. “Tucking can be uncomfortable and going to the bathroom and untucking can remind yourself of things you do not have.”

Tucking, according to the UCSF Transgender Care, is the practice of moving the penis and testicles towards the buttocks to allow for a “visibly smooth crotch contour.”

Aragon has been questioning everything: her past, her faith, her life purpose, her body.

“There’s days where I don’t want to keep going,” Aragon said.

On the days she’s gripping onto hope, Aragon tries to be present and grateful for her accomplishments. She holds onto “the hope of a better tomorrow, hope that one day I can leave a better footprint for the trans community.”

“I’m at a point where I live comfortably, where I can throw on some sweats and a sweater and go out into the world and people see me as a girl…I’m living my life the way I want,” said Aragon. “And yet I’m over here still fighting my body because I’m not satisfied now that I have the opportunity to get surgeries.”

Over time, the mirror became a way for Aragon to keep track of how she felt. She’d check it for positive or negative reinforcement but always came back to the same conclusion.

When Aragon looks into the mirror, she searches for her beauty. She hears the compliments she’s received and sees how she’s gotten over past insecurities.

Aragon said, “You were born the way you were to look and be who you are, so you have to own it and run with it.”

They’re nice to look at

Christina Hernandez enjoys exercising at the park. She goes for the open space and stays for the trees swaying high above. However, she has not been able to go to the park recently.

She recently became a stay-at-home mom who focuses on her husband and her sons, one who is in third grade and the other in eighth.

Hernandez loves being a mom and enters “mommy-mode” whenever need be, but she began feeling uncomfortable with her body after having kids.

“Mentally, I was okay. I don’t think I went through postpartum depression, thank god, but physically I was not happy,” Hernandez said. “I was overweight. I would eat and eat and eat. It became my comfort zone.”

This comfort zone soon became a source of discouragement.

“I become nitpicky and poke at how my panza (belly) looks,” said Hernandez. “I discourage myself, but I’m trying my best to get to that point where I feel good about myself.”

There are days she walks past her reflection in the mirror and thinks to herself, “Oh my god, I’m looking cute or whatever.”

Other days, the mirror focuses on her face. Her eyes get redirected to her hair, where she’ll separate a single silver strand from her caramel roots. She’ll flip the mirror around and focus on her acne scars.

Hernandez isn’t always in the mood to use foundation to conceal blemishes. Her platinum balayage is frequently in a bun, and, although she’s occasionally been asked if she’s mad, Hernandez always replies, “That’s just my face.”

While she’ll never fake a smile, her face lights up at the mention of her tattoo — a half sleeve on her left arm that, from a distance, appears as running water, but from close up reveals a smokey arrangement of roses where gloomy butterflies rest.

“Butterflies are pretty, and roses are pretty too,” Hernandez said. “They’re nice to look at.”

Fernando G Pacheco is a student journalist minoring in queer ethnic studies at San Francisco State. He writes from Los Angeles, CA. His favorite mornings...