Cultural Commodification: Inside the World of the Holistic Health and Wellness Industry

Detail of the black tourmaline necklace Ayanna King wears daily in San Francsico, Calif., on Oct. 12, 2021. (Avery Wilcox / Xpress Magazine)

Crystal shops on Instagram bring in followers by the thousands. CBD-infused beauty products take over store shelves. Available for purchase at the low starting price of $142 is a rose quartz dildo intended to raise your vibrations and “reawaken the heart.”

It’s a new age for the holistic health movement — but the consequences could be more than what we imagine.

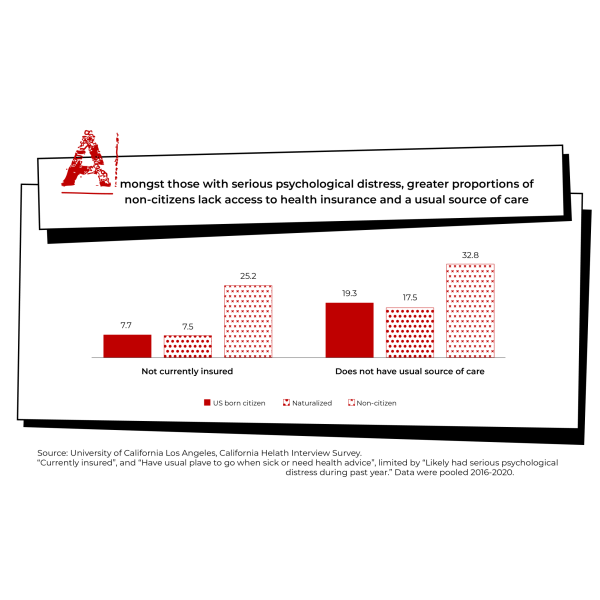

In 2021, management consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimated that the “global wellness market,” ranging in all categories from fitness to sleep to physical health, was priced at more than $1.5 trillion. Other studies, like one published by the Global Wellness Institute in 2018, found that the industry could be valued at nearly $4 trillion.

While the exact worth of the wellness market remains a debate, one thing is clear: holistic health is more lucrative now than it’s ever been. And like any industry worth its Himalayan rock salt, meeting the demands of its consumers can lead to a whole host of issues.

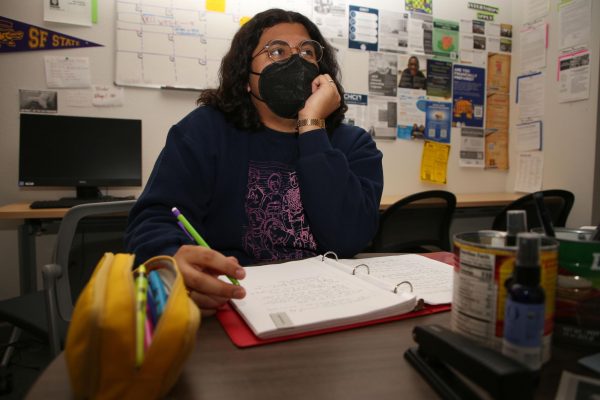

“It could just be marketing, but at the same time, I feel like my life has changed,” says Ayanna King, a junior at San Francisco State University, referring to the piece of moldavite she wears around her neck.

King, whose family is Caribbean, believed in spirits and aspects of the occult from a young age, but only recently became interested in crystals, tarot card readings and similar practices.

The source of her intrigue? Social media.

“I started seeing moldavite everywhere,” says King. “Anytime I looked on a website, I would see it. At the same time, I was going through a personal transformation, so when I saw it and they were like, ‘This crystal comes to you,’ I was like, ‘Oh, that makes a lot of sense.’”

After acquiring the moldavite necklace, King bought 28 more crystals within the next few weeks — she calls it her “little collection.” While she says she’s skeptical of people who claim crystals to be the end-all-be-all, King believes that “anything you want, you can manifest.”

“I definitely feel like crystals have certain powers,” King says. “I feel like everything happens for a reason.”

Although they have achieved mainstream popularity over the last decade, crystals, yoga and herbal medicine are more often associated with the stereotypes of the disconnected Hollywood celebrity (read: Gwyneth Paltrow) or an Instagram influencer than they are with the average American.

Even less often are these practices attributed to their respective cultures, particularly in the case of Native traditions and belief systems.

White sage, which is used by many Native tribes across North America for spiritual and medicinal purposes, sparked controversy online in 2018, with many people questioning whether or not the plant should be used by someone who is non-Native.

Common concerns that were discussed included misuse of the plant, moldy or low-quality product and overharvesting, especially in places like Southern California and Arizona.

Valerie Cabral, a junior at SFSU who is minoring in holistic health, says that she has received many comments about her field of study and its seemingly inherent contradiction with her Native American identity. Cabral also works as an administrative assistant at Indigenous Circle of Wellness, a Native American therapy center in Commerce, California.

“I do think that there are key concepts within holistic health that are beneficial that aren’t from Indigenous cultures but are proven to work within a medical context. Going into holistic health, I knew a lot of it is and will be a lot of stolen Indigenous practices from everywhere,” Cabral says.

What Cabral is referring to is known as ‘cultural appropriation’ — the act of imitating or performing the acts, behaviors and culture of a demographic in a way that is considered inappropriate or offensive.

It’s not just about the plant itself, she says. To Indigenous people, plants like white sage and sweetgrass represent something ancestral, something that can’t be described in capitalistic terms.

“Sage is viewed as medicine, but also as a relative,” Cabral says. “You’re seeing your relative be bought and used and mistreated.”

For Cabral, like many other Natives, cultural appropriation is a cruel reminder of the way Indigenous people have historically been treated.

“It’s not just this one practice you’re disrespecting. You’re disrespecting our entire nations, our entire livelihoods, us as individuals,” she says.

Robert Williamson, a senior at SFSU, believes that non-Native people are often drawn in by the allure of many Native American and Indigenous cultures, particularly by the wisdom and intuition that these cultures exhibit.

“I think people see that wisdom and want to extract from it,” they say. “It comes from a colonial mindset of just pure extraction, you know, ‘What can I take from this culture, what can I take from these people, and how can I flip it and profit off of it for my own personal gain?’”

Williamson, who is of Diné and Yurok ancestry, spends their days volunteering at the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, a Native-run land rematriation project based in Oakland. They point out the overharvesting of white sage and palo santo in the Americas, calling it a “desecration.”

It’s not just cultural appropriation that Williamson is concerned about. They point to the ableism, fatphobia and white supremacy that often runs rampant in spiritual and wellness circles.

“It’s almost predatory and abusive for these companies to make people feel bad about themselves, even though they’re trying to ‘lift’ people up,” Williamson says.

Senior Tim Wells, one of the first members of SFSU’s Occult Student Alliance (OSA), says that “whiteness is definitely at the forefront of mysticism.”

Wells, who is Black, says that representations of spiritualists as primarily white are often misleading and incorrect. While people of color are more likely to be associated with practices such as voodoo, particularly in the United States, they exist in every circle of spiritualism.

“When someone makes a comment like ‘White woman crystal magic,’ it’s like, ‘Well, yeah, kinda!’” He says, laughing. “The idea of spiritualism they’re thinking of is white.”

Wells attributes this for-profit approach of spirituality and holistic health to the industry itself, not only its consumers. The exploitation of spiritualism, holistic practices and closed Native American practices doesn’t accurately represent spiritualism as a whole, he says.

Like anything that gains traction on social media, spiritualism has become ripe for commodification.

“At the end of the day, what we’re trying to do is cultivate relationships,” says Wells. “And part of cultivating relationships is respect.”

Cash Grace Martinez (he/they) is a 2Spirit transgender & Southern Pomo storyteller based in San Francisco. His work has been featured in the Press...

![[From left to right] Joseph Escobedo, Mariana Del Toro, Oliver Elias Tinoco and Rogelio Cruz, Latinx Queer Club officers, introduce themselves to members in the meeting room on the second floor of the Cesar Chavez Student Center.](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/mag_theirown_DH_014-600x400.jpg)