The Dreamer’s Path

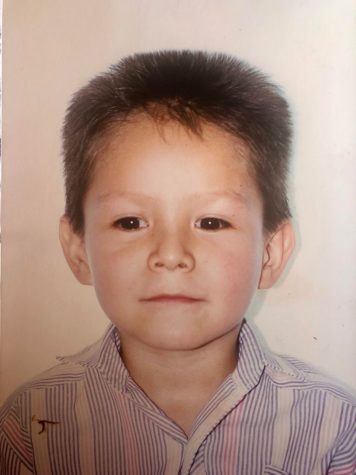

Portraitof Luis De Paz Fernandez on campus in San Francisco on Nov. 4, 2021. Fernandez studied at SF State for both his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree. (Morgan Ellis / Xpress Magazine)

The sun illuminated the pavement of Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley, where the columns would raise students’ eyes to the sky. The Latin phrase fiat lux, meaning “let there be light,” resting at the top of Sather Gate was the only star in sight.

Luis de Paz Fernandez could see himself there, within the university tour guide’s story that detailed the life of a busy student being greeted by the slap of the sun on their dilated eyes after exiting an hour-long class inside a dimly lit lecture hall.

“Oh yeah, I’m going to apply here,” Fernandez said.

At the age of 22 in 2012, Fernandez applied to be a DACA recipient and became a beneficiary of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival, which grants permission to live and work in the United States for a two-year period. Recipients can renew this with an update of their civil standing and progress for $495.

The desire for a future resonates with all “Dreamers,” yet the journey towards stability seems impossible due to the expectations and restrictions put on Dreamers via conditional residency, work permits and frequent renewal dates.

The term Dreamer is derived from the Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, known as the DREAM Act. The Act is meant to grant temporary conditional residency and work authorization for young immigrants and, if qualifications are satisfied, permanent residency.

The Act has been introduced various times in Congress since 2001. Although the term Dreamers has advanced into everyday vernacular, the Act has not been passed into law.

“I started a family, was married and had my daughter, but it was stressful when my DACA was about to expire,” Fernandez said. “Do I keep working? What’s going to happen? Sometimes it takes forever to renew. Then you start realizing that you’re building something but the foundation is very shaky, because any second that can be taken away.”

The DREAM Act and DACA are both intended for immigrants who arrived in the U.S. before turning 16 years old and were under 31 years old as of June 15, 2012. It doesn’t ensure that a recipient’s parents, nor other immigrants who arrived at a later age, will be granted conditional residency.

Jairo “Vanni” Castillo, a 27-year-old San Francisco State alumnus, was hesitant to apply nine years ago when DACA was first approved.

“We were sharing such delicate information such as your full name and address. We went from this place of being unknown to being known,” Castillo said.

Castillo applied, feeling unsure but hoping DACA’s proposal would be accomplished. If so, there’d be an expansion of employment options with a greater increase.

“I already knew I was undocumented and the opportunities to find a job were going to be more limited,” Castillo said.

DACA offers an expansion of job opportunities by providing a work permit through a conditional social security number that an employer can verify.

Castillo says the benefits of DACA are a privilege that many other undocumented people aren’t typically granted.

In 2017, Castillo was working at a Safeway grocery store. Red hats and “Make America Great Again” shirts would often make an appearance and create animosity between co-workers who would express personal and political beliefs.

Castillo did not want trouble, nor could he afford to risk getting fired from his primary job.

Similar to Castillo’s feelings of restriction, Fernandez grew up feeling a level of limitation. Most of his behavior derived from his experience as an immigrant.

During Fernandez’s time in K-12, he noticed how students who “misbehaved” wouldn’t be taken seriously and their commitment to their education would be questioned. “I was afraid that if I got in trouble I’d get deported or would bring attention to my family,” Fernandez said.

As a result of the restriction, Castillo questioned if he had assimilated himself to match his coworkers. He’d mirror others’ mannerisms, speak English with certainty, except he wouldn’t talk politics nor debate other’s beliefs.

Castillo focused on getting through work by keeping himself sheltered beneath his skin. Safeway just wasn’t his safe place.

“You are leaving everything behind just to try. You don’t even get a guarantee that you’re going to be accepted by this group of people,” he said. “You’re risking a lot for nothing.”

Castillo is not convinced he assimilated. He believes to assimilate is to resign from one’s cultural roots, leaving behind one’s origin language, like trying to pull out a root embedded deep within the soil.

“We don’t exist other than just as a number to make a profit. We don’t exist as humans that make this country better, for our creativity and the work that we do,” Castillo said. “They want our culture, but they don’t want our people.”

Fernandez is now the executive assistant to SF State President Lynn Mahoney. He was previously the coordinator for the Dream Resource Center. He didn’t apply to Berkeley but is considering the UC as a potential for a doctorate. Instead, The Skyline Community College alumnus completed his bachelor’s and master’s at SF State.

The Campaign for College Opportunity reported that over 64,000 undocumented students are currently enrolled in a California Community College, California State University and University of California systems.

The same report found that one out of five undocumented adults ages 25 and older attended college, 10% of which earned a bachelor’s, master’s or professional degree.

Sharet Garcia became a DACA Recipient in 2017 after being told she did not qualify for DACA in earlier years. She had been paying for school entirely out of pocket up until that point.

“It’s a feeling of excitement when at least one door opens to you within the DACA program, but then you come back and realize that door can close any day,” Garcia said.

Garcia was facing a difficult time in school. On top of being a full-time student, she was also working a full-time job. At school, she was constantly advocating for herself and explaining her livelihood to professors.

Two years before becoming a DACA recipient, Garcia felt overworked. She questioned whether or not she’d been wasting her time pursuing her education. At the time, she wasn’t seeing any progress in her citizenship status.

She debated going back to Mexico until she met with an immigration lawyer, one who could not change her status but made her feel understood.

“She reminded me by saying, ‘I know you’re frustrated and this is upsetting, but you have worked very hard to be where you are right now. I can’t tell you what to do but I can tell you that you wouldn’t want all that to go to waste,’” Garcia said.

She left the immigration office knowing her lawyer was right. She exercised patience and started to advocate for herself at school and work and eventually graduated from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles County.

Through DACA, Garcia was able to find jobs more suitable to her liking, but a feeling of disconnection from her community was amplified once she entered the professional field.

In 2019, Garcia founded The Undocuprofessional Network, a network aimed to provide new levels of employment and educational opportunities for the undocumented community.

Even though Garcia was experiencing doubt, she still wanted to create a platform to provide support for thousands of undocumented individuals.

According to Migration Policy Institute, approximately 45,000 undocumented people reside in San Francisco County and an estimated 951,000 in Los Angeles County, with an approximate total of 2,739,000 in California.

The Undocuprofessionals Network provides a mentorship program that connects undocumented mentees with undocumented professionals. The network has a mixed-status community, meaning there are people who are DACA recipients, TPS holders, undocumented or in the process of adjusting their citizenship status.

“There are actually a lot (of people) in the community that are completely undocumented, no DACA, and are professionals. A lot of them are entrepreneurs in different fields,” Garcia said.

According to the 2020 State of Latino Entrepreneurship Report, there has been a 34% increase of Latinx-owned businesses in the span of the past 10 years.

For some undocumented individuals, they’ve stopped waiting within the uncertainty of citizenship and started creating their own path to a stable future.

Castillo explains that the path to citizenship would grant people the opportunity to reconnect with their families — a desire craved by people who can travel out of the U.S. but don’t have a secure return route.

He reminisces about family members that have passed away, of funerals he wasn’t able to attend and of goodbyes he’s given over the phone.

“It’s for the nostalgia, being able to stop remembering and actually going back to relive the experience, after, who knows, 20-30 years of not being able to go back to their place,” Castillo said.

For some people, “going back” means reconnecting with family in a way an international call can’t.

“I think it’s the fact that people want to see their families again, especially since a lot of them have passed away,” Castillo said. “And not being able to say goodbye physically, has become one of the biggest challenges for the undocumented community.”

Fernando G Pacheco is a student journalist minoring in queer ethnic studies at San Francisco State. He writes from Los Angeles, CA. His favorite mornings...