Ximena Loeza (she/they) is a 22-year-old Bay Area native. She enjoys writing about beauty, fashion, social justice, queer culture, and all things pop culture.

December 15, 2021

As the studio manager announces closing time, the heads of several hard-working potters shoot up in shock. They scramble to clean up their workstations and make their final touches on their pieces. For these potters and many others, it’s easy to get lost in the clay, where hours become minutes and closing time comes too quickly.

Something that makes ceramics stand out from many art forms is the community based around it. Studios are communal spaces where potters are forced to share facilities and materials, like glazes, tools, clay and kilns.

Clayroom is a fairly new studio with two locations in San Francisco. Their Portero location opened in 2018 and their South of Market (SoMa) location opened in 2020 at the start of the pandemic. But even with unlucky timing, Clayroom has been able to flourish and become a popular studio in San Francisco. They offer a variety of classes for beginners and skilled potters alike. Studios like Clayroom have created a safe space for potters to create and learn new things, no matter their skill levels.

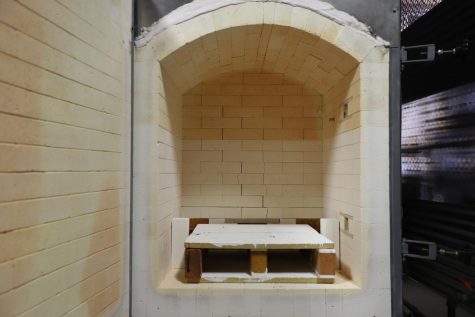

Jeffrey Downing, a ceramics professor at San Francisco State University, has been a working artist for over 20 years. He helps students unload their pieces from the kiln with the help of former student Julia Rinklin, a studio manager at Clay by the Bay, a ceramics studio in San Francisco that has been open for six years.

Rinklin shows how different glazes have changed in the kiln on various pieces. She talks about the importance of understanding how a kiln works and the differences between various types of kilns. She picks up a piece and shows it to Downing, asking why the color of the glaze changed in the kiln.

“Do you think it could’ve been because we used a brick kiln? Maybe an electric kiln would’ve given it a more blue hue,” says Rinklin.

Downing thinks people are drawn to ceramics because of the hands-on aspect, being able to be much more connected to the clay.

“With painting, you’re using tools like brushes and an easel. With ceramics, your hands are in the clay, melding it into a vision you have in your head and pushing and pulling the clay. It’s a deeper connection to the clay,” says Downing.

The community surrounding ceramics and pottery is what brings a lot of potters, like 25-year-old Jamie Westermyer, back to the art. Westermyer is a co-studio manager at Clayroom as well as the head of instruction of Clayroom’s classes.

“All of my friends that I’ve met in the Bay Area are because of Clayroom. The community that’s fostered there is just really amazing,” says Westermeyer.

She joined Clayroom’s SoMa location two weeks after their opening in 2020 and has been able to witness the studio grow and change.

“When we first started, there weren’t a lot of members and they weren’t doing classes yet. But I’ve seen it quite take off. A lot of people during the pandemic lost their jobs and I saw a lot of people start coming in every day,” says Westermeyer.

Westermyer feels as though ceramics is vastly different from other art mediums. She mentions how you can take a painting or a drawing home, but it’s not really possible to take home a working pottery piece.

She feels as though she has created a strong bond with ceramics, a bond that is wholesome, filled with curiosity and free of any competitiveness or hostility.

Westermyer’s favorite kinds of pieces to make are dishware, especially mugs. She sees a lot of people in the food industry, especially chefs, are also interested in ceramics. She thinks food and ceramics go hand in hand, and that understanding and appreciating the dishes being eaten off of are just as important as appreciating the food being eaten.

“It’s actually so crazy how many members and students at the studio have some type of culinary background,” says Westermeyer. “It’s an all-encompassing experience when you’re able to have your hand in both.”

This is something that Downing has noticed as well. He talks about how whenever he goes out to eat, he’s always admiring the dishware while he eats.

“Once you start ceramics, you notice every little detail about dishware at restaurants and food establishments,” says Downing, turning his head to glance at Rinklin as she examines the bottom of a bowl freshly pulled from the kiln. Downing continues, “Especially the bottom of dishware. The bottom can tell you so much about a piece like a maker’s mark or a special design.”

This is something that Kelsey Segasser, 24-year-old co-studio manager at Clayroom, finds to be the most important part of a pottery piece. She has a passion for coming up with new and innovative classes for the studio as well as slip design techniques, which is when a potter uses watered-down clay to create designs or dimensions on the clay. She has also gotten into the habit of looking at the bottom of pottery pieces, as she believes they hold a story and a lot of significance.

“Every ceramicist has a signature or a stamp or a specific mark that they use to mark all their work. And when you see that you know this is made from a person, not made from a machine, and you just immediately feel super connected to that person,” says Segasser.

Clayroom holds classes almost every day that range from “Intro to Clay,” “Intro to Furniture Making on the Lathe” to a “Queen Gambit” class where an instructor walks students through making their own chess set, including both woodworking, mold-making and slip casting.

Segasser feels as though the variety helps keep their longtime members out of ruts and encourages them to keep learning new things.

“People definitely tend to get stuck in their style. It’s a way to kind of push them out of their comfort zone a little bit and try something new,” says Segasser.

She mentions this idea of a “flow state” in pottery, which could be described as the feeling of getting lost in the clay and falling under some sort of trance while throwing clay. Segasser says this can happen especially during the process of trimming, where a potter trims excess clay and shapes the clay when it is in a leather-hard state.

“The wheel is literally hypnotizing. You will be so surprised how quickly an hour goes by. It feels like it’s been like 10 minutes and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, I can’t believe I’ve been here for an hour already,’” says Segasser.

Westermeyer has a habit of entering this “flow state” as well. In her evening classes, time gets away from her easily. She gets distracted talking to her students, inquiring about what they’re making and how they’re doing. Even though the night class lasts almost three hours, she never thinks it’s enough time.

Ximena Loeza (she/they) is a 22-year-old Bay Area native. She enjoys writing about beauty, fashion, social justice, queer culture, and all things pop culture.