From the Ground Up: A Revolution at State

December 15, 2021

On a windy Tuesday afternoon, holding a cup of coffee from Cafe Rosso and wearing a university-branded mask, fourth-year student Ja’Corey Bowens sits on the steps of the Cesar Chavez Student Center, a monolithic feature of San Francisco State University’s campus.

Since the start of the fall semester, Bowens has served as the president for the Black Student Union, which provides a community space for the university’s Black student body. Founded in 1966, it was the first organization of its kind in the country.

According to William Orrick, author of “Shut It Down! A College in Crisis,” at the time of the BSU’s founding, only 4% of students at San Francisco State University, then called San Francisco State College, were Black. Five decades later, students of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds, Black, Indigenous, Latino, Asian, Palestinian, now populate SF State’s campus.

Events discussing racial issues, police brutality and intersectionality are held on a regular basis. Classes focusing on the experiences of marginalized groups — HIV-positive people of color, queer and transgender Native Americans, undocumented Latina immigrants — are offered each semester. University course requirements dictate that all students, regardless of major, must take at least one Ethnic Studies course in the time they are on campus.

In spaces like the BSU, Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations (SKINS) and General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS), students of color can find community, support and belonging among their peers.

“In every part of what is now America, there’s little to no spaces for Indigenous people,” says Valerie Cabral, one of the facilitators for SKINS.

SKINS was founded by activist and SF State alumnus Richard Oakes of the Mohawk Nation. The group directly supported the Third World Liberation Front during the 1968 strikes.

“To have a space specifically constructed for Native students on campus was something that was unheard of to me, especially coming from my high school where our mascot was a ‘Chief,’” Cabral says.

Still, the image that the university often paints of itself as a progressive utopia is different from the one that many students of color face each day when they arrive for their classes. Feeling like there is little support from the administration, students of color often turn to each other for support and advice.

Many student leaders, such as Bowens, as well as the BSU’s External Vice President Lee Lockhart, are beginning to feel the weight pressing down. In the last four years, Bowens says they’ve watched the number of Black students in their classes dwindle.

“I was on the Afrocentric floor my freshman year and we had about 25 of us living there,” they say. “Now I’m walking across the stage, and there’s only three of us.”

Lockhart joined the BSU his freshman year as a general member, later serving as financial officer in his third year.

“I didn’t really think that I’d ever be in a (BSU) leadership position,” he says. His role as External Vice President is to provide support to other BSU board members, as well as their general members.

“Something we’ve always talked about in BSU is how to support Black students better,” Lockhart says. “It’s really sad that we still have to worry about that.”

The presence of student leaders and activists from 1968 to now is a driving force behind SF State’s radical legacy — and the work, they say, is far from over.

All power to the people

According to Orrick, tensions had been building on SF State’s campus for years prior. However, the ultimate catalyst for the Ethnic Studies strike and resulting academic movement was the suspension of teaching assistant George Mason Murray, an SF State graduate student and the minister of education for the Black Panther Party.

Murray was invited to speak at Fresno State College in October 1968, where he called for Black students to arm themselves against white supremacists disguised as school administrators.

“We are slaves,” Murray had said. “And the only way to become free is to kill all the slave masters. Political power comes from the barrel of a gun.”

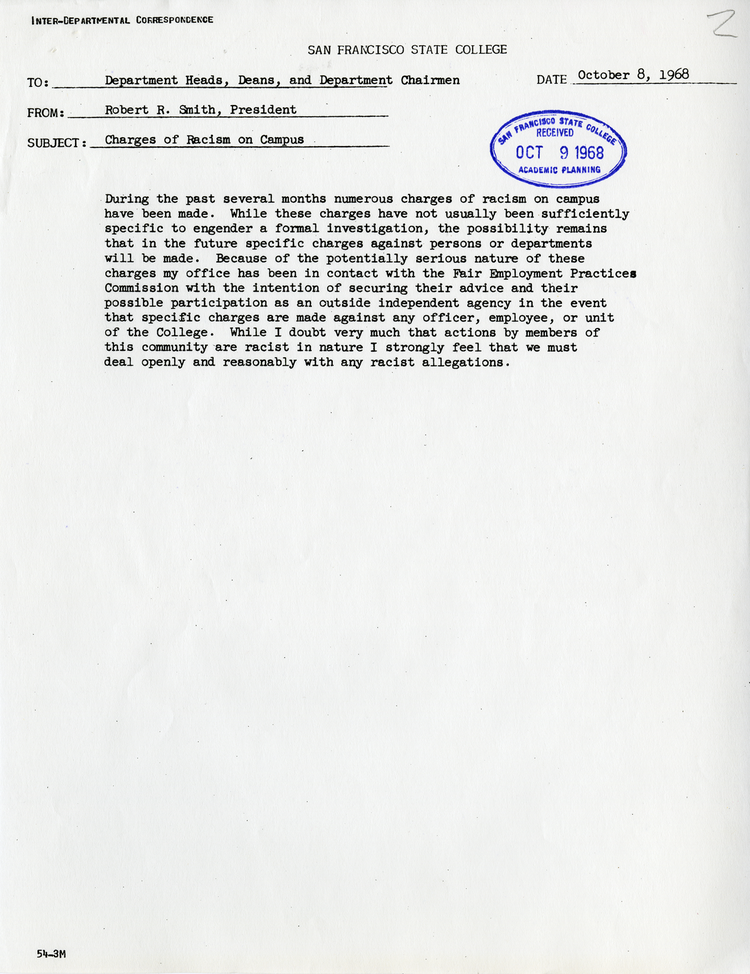

According to Orrick, while the college’s president at the time, Dr. Robert Smith, refused requests to fire Murray, his hand was eventually forced by the board of trustees. Murray was officially suspended on November 1, 1968. Protests followed soon after.

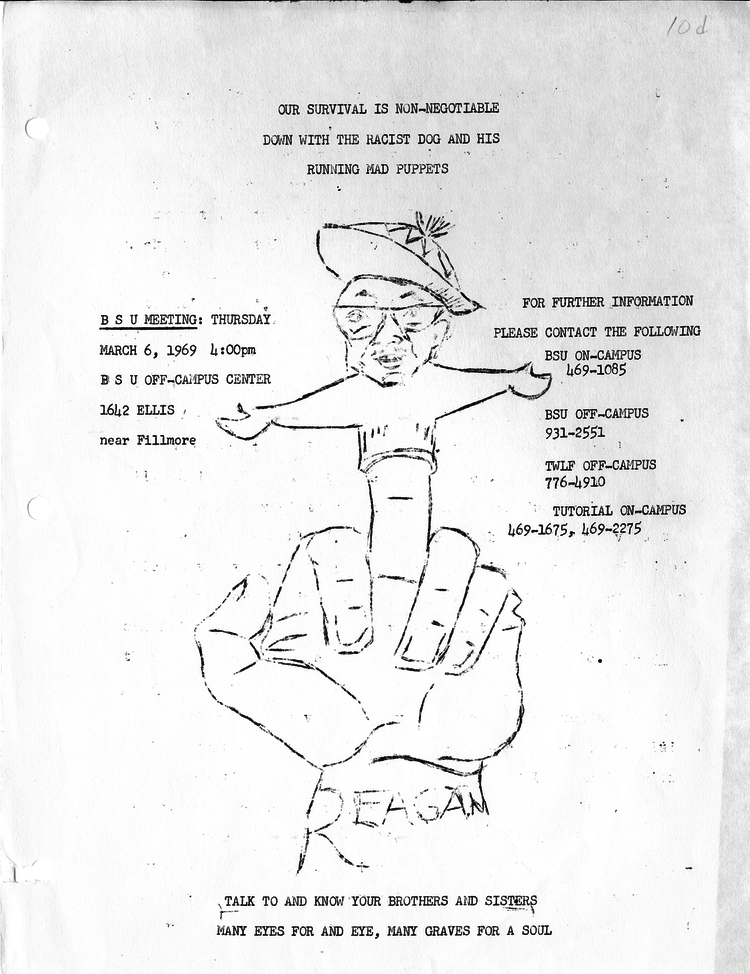

A mere five days later, the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), a coalition of Black, Latino, Indigenous and Asian students, as well as white allies, unified and began striking, demanding that the Black Studies program be expanded and that Murray be reinstated to his teaching position.

“[Administration tries] to make us believe we’re free when our brother and sister students are made victims,” reads one flyer, published by the first Black Student Union while the strike was ongoing. “We are not educated here, we are trained.”

According to the SF State Strike Collections, by the spring of 1969, more than 800 protestors had been arrested and class attendance had dropped to a measly 37%. Police officers, sporting full riot gear and carrying batons, beat and brutalized students on a daily basis. Violence on the college’s campus had become a common sight.

Still, Orrick says, the BSU and TWLF held steadfast in their convictions and on March 20, 1969, an agreement was reached between strikers and administration. By the next fall, the first College of Ethnic Studies was established in the United States.

The largest student-led strike in US history had ended, but the fight for a safe and equal education for students of color at San Francisco State University was still in its infancy.

The struggle continues

In 2016, the College of Ethnic Studies as well as its adjacent programs were facing a major financial crisis. Faculty and staff stated that the issues were due to budget cuts from the university, while university officials claimed, in comments then made to Golden Gate Xpress, that their dire financial straits had resulted from the College of Ethnic Studies spending more than what was included in their budget allocation.

In response, a group of concerned undergraduates unified, leading to the beginning of the second strike in SFSU’s history.

According to archival information made available by the College of Ethnic Studies, the demonstration was spearheaded by undergraduates Hassani Bell, Julia Retzlaff, Ahkeel Mestayer and Sachiel Rosen. A list of ten demands, which focused on the reallocation of funds to the College of Ethnic Studies, as well as increasing university requirements for Ethnic Studies courses, was published on their Facebook page.

That May, following 10 days of a hunger strike which resulted in one hospitalization, the group’s demands were finally met by then-SFSU President Leslie Wong. In a written statement published by President Wong, close to half a million dollars was dedicated to funding the College of Ethnic Studies.

Bell, who was in his freshman year at the time of the hunger strike, was murdered in September of this year by an unknown gunman. Bowens spoke of their personal connection to Bell as both a friend and comrade, as well as the impact his work and life had left on members of the BSU.

“A lot of these individuals are still going unrecognized today,” says Bowens. “It’s my job not only to continue recognizing them, but making sure we’re honoring the people who came before us, because we wouldn’t be here without any of our alumni from BSU.”

Bowens says that much of their time at SF State has been spent advocating for the safety, education and rights of other Black students.

As Bowens and Lockhart point out, much of the campus discussion following George Floyd’s death by police in May 2020 was focused on policing, security and racial profiling. Yet, they both say very little has changed or improved in the relationship between campus police and students of color.

“A lot of the stuff Ja’Corey and I did to advocate and support Black students, whether that was with police abolition or just trying to get them to listen to BSU, was really difficult,” says Lockhart. “It wasn’t a problem getting into the space. I think President Mahoney does a great job of making herself available but I think the follow-through hasn’t been there.”

Promises made by the administration in the months following Floyd’s death, such as a review of the University Police Department’s budget or the implementation of Mental Health Response Teams in residential halls, were left unfulfilled, according to Bowens and Lockhart.

“It’s disappointing to see that. It’s annoying that we get to be in these spaces, but then no action comes from it,” Lockhart adds.

For Bowens, who spent two years working in Associated Students (AS), the anti-Blackness they say they experienced from the university and student government became too much to ignore. Their decision to leave AS, in the end, was nothing less than bittersweet, they say.

“Administration doesn’t want to accept mistakes that they’ve made, but they’re willing to embrace anything that goes right,” Bowens says. “That was hard to have to rationalize, just knowing that you pour so much in and you’re not even a header on this chapter of history.”

Aisha Hawkins, a long-time member of SKINS, says that the support from the university, as well as from AS, more often than not feels restrictive, bordering on censorship.

“Administration and Associated Students tell you, ‘Here’s a space where you guys can be expressive,’ but they’re not giving us the freedom to do it,” says Hawkins, who is Black, Indigenous and queer. “They definitely restrict how much we can represent ourselves.”

Joshua Ochoa, who serves as the president of AS, says in an email that he and AS are actively working to address issues within the system and address the concerns of student organizations.

“I would ensure that AS remains an organization by and for the students at SFSU, in addition to one that stands against anti-Blackness and what we can do as a campus to combat it,” Ochoa says. “In the past, we’ve done trainings and had important conversations around anti-Blackness and how to combat it throughout campus, but I know that we can always do more to address those concerns as we continue to fight and advocate for students.”

A path forward

Campus conditions for students of color and the organizations that serve them might seem bleak, but Bowens says that there is still hope to improve the lives of Black, Indigenous and other students of color at SF State.

“It starts off first with them listening to student workers and student leaders,” Bowens says. “No one’s gonna do anything about these problems if we, as Black students, don’t say anything.”

Bowens and Lockhart both agree that focusing on making BSU an intersectional, welcoming place for all Black identities is one of the student organization’s main goals at this point in time. In the past, Bowens says, queer Black students have felt uncomfortable attending BSU.

“The Black Student Union is inherently supposed to be an inclusive space,” Bowens says. “How are we changing that narrative to make sure that BSU is holding onto that? Yes, we’re an inclusive space for all, but what are we doing to prove that we’re being inclusive?”

Lockhart says that BSU has focused on making programming more diverse and accessible to Black students of other marginalized identities.

“I hope to see BSU continue to be a space for all Black students, and not the ones that we typically think of, like Black heterosexual males, in the space,” he says.

He added that breaking the existing misperception of the BSU would encourage more Black students to get involved and find their community at SF State.

“Our struggles are interconnected,” Bowens says. “We’re all just Black students and we’re here to be in community with one another.”