This story was corrected for spelling.

Everyday, students with disabilities characterized as physical, developmental or related to learning are forced to tackle difficulties within education. Some classrooms are missing teacher aids, others are too crowded and overstimulating.

As more conversations about inclusionary learning, budget cuts and accessible education continue to enter the public eye, it is important to recognize the programs and staff that impact students with disabilities.

Despite the availability of resources and support programs, students at the furthest ends of the K-12 spectrum are often left out of the conversation when it comes to accessible special education. Early childhood and elementary special education and college programs often lack the same support as general education at the middle and high school levels.

Special education aims to provide students with disabilities equitable and accessible education through individualized learning plans and tailored accommodations that look different for each family and student.

At the college level, students with disabilities are suddenly faced with needing to make decisions for their education on their own without the guidance of a school counselor or special education teacher. It can get overwhelming on top of the already existing challenges with standard college practices, such as financial aid, enrollment and housing.

The Inclusion Pilot Project at San Francisco State University aims to provide students with intellectual and developmental disabilities an accessible education by allowing students to enroll in classes of their choosing. The project walks students through a person-centered plan while also assisting them with both professional goals, such as setting up a portfolio, and social goals.

Amber Dinov, program coordinator for the Inclusion Pilot Project, stresses that the project exists out of the students’ desire for a higher education.

“Our society has put this label on people with intellectual and developmental disabilities that they’re kind, they’re helpful. They can do simple things. However, that’s not the case,” Dinov said. “There’s a capacity for more, there’s a want for more. One of the cornerstones of our project is not everybody needs college, but everyone should be able to access education.”

The program and its staff is funded by the Department of Rehabilitation, which supports students with disabilities from youth to adulthood. The Inclusion Pilot Project, or the IPP, works through something called Open University, which allows students to purchase open seats in classes.

After getting registered in the program and enrolled within classes, students are assigned a peer mentor that works with them throughout their journey.

Ash Verwiel is currently a peer mentor for Augustin “Auggy” Garcia who prefers to go by his first name. The two have worked closely for six semesters now as Auggy continues to take cinema and animation classes through the IPP.

Verwiel reflects on when he was introduced to the program via Handshake, saying he had no idea about what kind of barriers students with disabilities face until he started working at the IPP.

Verwiel started by assisting Auggy with his coursework and being physically present in the classroom. Now he is helping Auggy with finding internships or job opportunities while working together to build his portfolio of different artwork and films.

Verwiel says their favorite part of the experience has been seeing Auggy grow within his academics and interests. He speaks to Auggy directly, saying how proud he is of him.

“You always had a whole world in your head, and now you kind of know how to make that come to life,” Verwiel said.

He goes on to talk about how important the program is for Auggy. “I think that’s part of the accessibility, right? Now you have all the tools and resources to make that come out, so that’s really cool,” Verwiel said with a smile on their face.

He shares how the program impacts the greater community as well. “I think what professors often forget is that their classroom is also enriched by adding inclusion students because it just adds another layer of life and diversity and, like, another perspective that makes it more reflective of real life, you know?” Verwiel said.

When Auggy first came to SF State, he didn’t know how many classes were available or anything about different resources such as the Cesar Chavez Student Center. Continuing into his sixth semester, Auggy has now honed into his animation and production skills and has directed some of his own films.

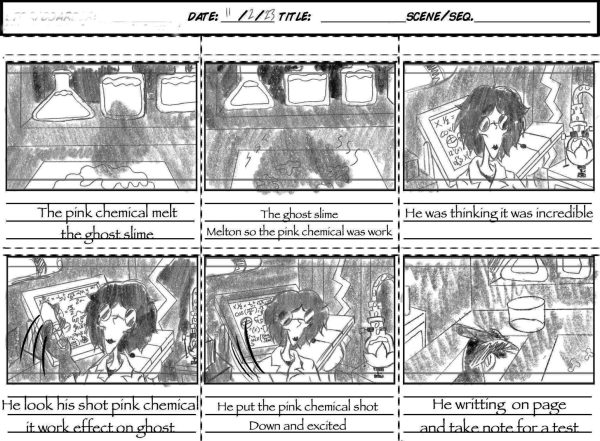

“To my own dreams, I want to study about animation and making movies,” Auggy said. “And more importantly be a director, storyboard artist, and animator.” Auggy’s portfolio and his work can be found here.

Despite its small presence on campus, the IPP has greatly impacted the students enrolled in the program seeking higher education and achieving their dreams.

“There’s not any community that isn’t touched by disability, and disability should be embraced,” Dinov said. “Disability is not a bad word, it’s not a negative thing, it’s just a part of what it is to be alive.”

Dinov says the program is like a mushroom spore, starting with the students and branching out to their peers, their professors and their communities.

“We love that our peer mentors leave us with the understanding that people with intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities are funny, bright, artistic and fun to be around and important,” Dinov said. “The professors that we work with see that, and it changes how they teach the next semester. When somebody leaves us and graduates, the idea of accessibility, the idea of inclusion, goes with them into that new space.”

On the opposite end, early childhood and elementary special education educators find themselves struggling with staffing issues and apathy from administration, yet they still love what they do.

Kimberley Anderson is the main teacher for the Special Education Day Class at Dolores Huerta Elementary School. She works with a handful of students ranging from grades three through five with different disabilities and adjusts to their every need while also trying to follow rules the school enforces.

Her classroom is full of sight words and feelings flashcards labeled with “calm, choice, no, etc”, and alternative seating for the students. The kids each receive assistive devices and iPads that read out something they need to communicate if they can’t do so verbally. Every little thing in Anderson’s classroom is set up in a way to help her students and accommodate any sensory challenges.

“If students don’t feel successful early on, that can impact them their entire lives,” Anderson said. “They can go through their entire elementary school career thinking, I can’t read, I can’t do math, I don’t have any friends and that’s going to impact them in middle school [and beyond]. So we need to really set them up for success at the very beginning.”

One of the issues with special education that Anderson mentions is the lack of funding for flushed out special education programs and staff. Citing the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990, which mandates schools to offer equitable and free public education to those with disabilities, Anderson explains that special education is simply too expensive for schools.

“It’s a federal mandate, so it has to be done,” Anderson said, “but the government isn’t actually funding it, so school districts are scrambling to pay for this. I’m hoping we get a federal administration that respects and funds special education.”

Another issue that Anderson faces is that special education teachers feel isolated from general education and that they aren’t supported by their schools.

“If we had, I think, better training for all teachers, general education as well as administration, then things would be more cohesive,” she said.

Anderson explains it as an “attitude issue” towards special education in that it is not being built into college programs for education.

Melissa O’Mahony, the assistant director at Stretch the Imagination preschool and former graduate of the SF State Department of Special Education, shares Anderson’s viewpoint of integrating special education early on into someone’s career in education.

O’Mahony received her Master of Early Childhood Special Education and now currently lectures at the university while overseeing graduate students and student teachers. At Stretch the Imagination, she acts as a liaison and mentor between families and teachers for students diagnosed with disabilities.

According to O’Mahony, if someone wants to be an educator in California they need to first choose if they will enter general or special education. She believes that this fosters an idea of “separation” in an educator’s training early on.

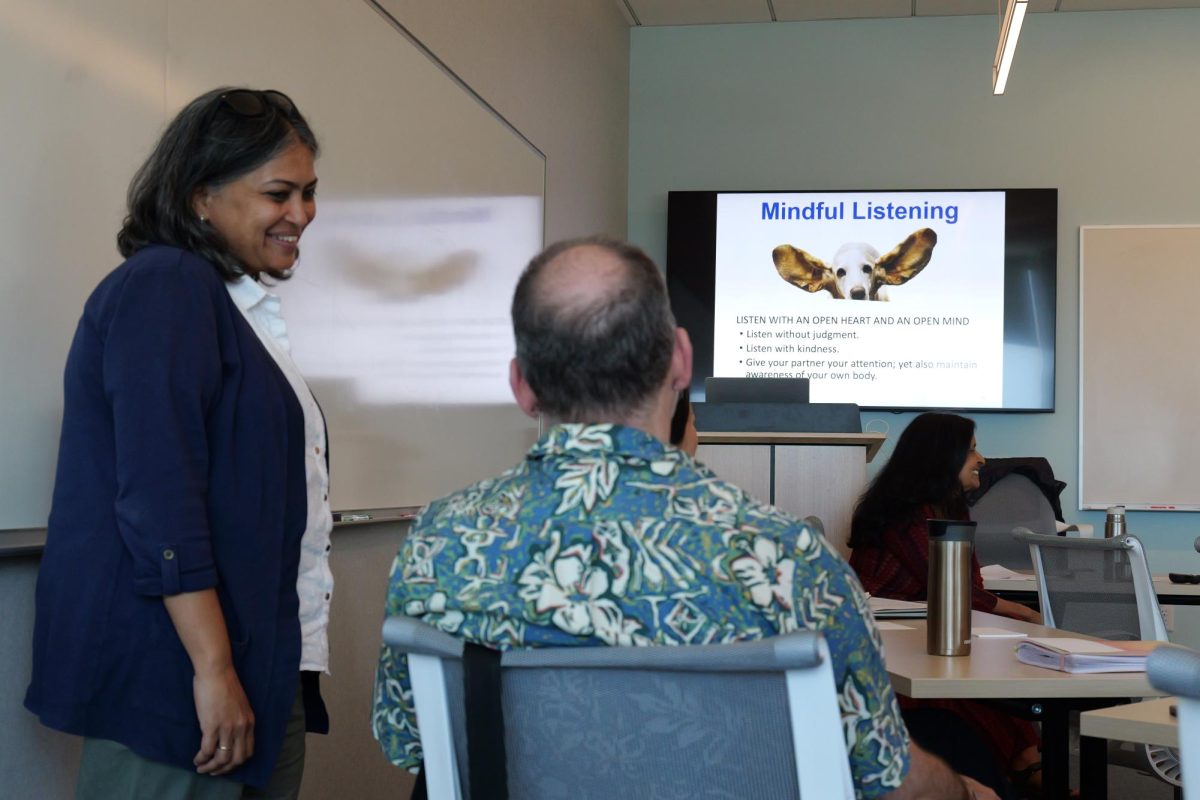

When asked about how she tries to combat the “attitude issue” within her staff, O’Mahony explains that it helps that she has a role of superiority, but that she also takes the extra step to actively listen to her teacher’s frustrations, anxieties and needs while offering suggestions.

“I do think the mindset is ‘this is hard, I can’t do this, I’m afraid, this is a lot of responsibility,’” O’Mahony said. “So with that pushback, the underneath is actually really valid and valuable to look at.”

She shares that people commonly have misconceptions about the difficulty of early childhood education and the ability of students. “Yeah, I think there’s a lack of awareness and understanding of how crucial those years are and how much the children are able to learn.”

When asked about the importance of accessible special education for students as young as preschool age, O’Mahony said that early intervention has proven to be beneficial in setting students and families up to be successful later on.

Educators like Anderson and O’Mahony work every day to dispel any stigma around special education while trying to bring to light some of the difficulties they face. People looking to go into fields such as education, psychology, health and more will eventually find themselves working with students with disabilities.

Anderson encourages people to take on an open mind when thinking about special education and the diversity within communities. She strongly believes in students with different disabilities taking up space within their communities to encourage accessibility.

When asked about how to start that process and mentality, Anderson says it’s always about visibility.

“I think having classes like mine on campus, being visible and being a valuable part of our community [is important], which is why I love my school too because we are extremely inclusive. Other students are going to school alongside kids with Down’s Syndrome, with Autism, in wheelchairs, and with significant and multiple disabilities and they are seeing them as peers,” said Anderson. “It’s going to take this new generation having positive experiences with people with disabilities.”

Kim Anderson • Dec 12, 2024 at 9:07 pm

Thank you for writing this! You did an amazing job. Great work! I hope more people read this and understand the importance of inclusive practices.