Written By Chantel Genest

Photographed by Lorisa Salvatin

You are acutely aware of a bang and a roar, a drum cymbal between a ticking beat traveling from your left to your right. A toad croaks amidst the mire beneath you, a deep hooting owl hidden in the trees above you. Chirps and a buzzing of a busy forest evade your surroundings. Silence. Water trickles off of the walls, a child’s utterance coming towards you from the distance. Ascending high and low, far and near, a makeshift symphony heightens your auditory senses as you sink into the pitch-black world consuming the remains of your sightless perception. You are experiencing the Audium

“I gradually fell into a trance state where I was somewhat awake and somewhat asleep,” says Ben Slater, twenty-five. “The fragment of noises brought memories in and out of my mind and made me more aware of time.”

As you pass the ticket booth and make your way into the foyer, you at once cannot help but to look all around you. Moving images of waterfalls stream across the walls and the echo of dripping liquid takes hold of your auditory senses. From the moment you enter the Audium building the experience has begun.

Once eight-thirty strikes you will assemble into a faintly lit room and choose from the forty-nine plastic folding chairs set up in a sphere around the dome-like theater. The lights begin to dim little by little until you find yourself in complete darkness. For the next ninety minutes, if you can handle it, you will be entrapped by a series of noises. Not quite together, yet not far apart, from children laughing to puddles splashing a chain of sounds bring you into a new perceptual awareness.

In the 1950’s, space was still an unexplored element of music composition due to the lack of audio technology available. Composer Stan Shaff and equipment designer Doug McEachern shared an idea that space was capable of revealing a new musical language.

Together the SF State alumni took their idea and made it reality. In 1967 the first Audium location opened up, the only space of its kind constructed specifically for sound movement and utilizing the entire environment as a compositional tool. At that time the performance was created through only forty-four speakers.

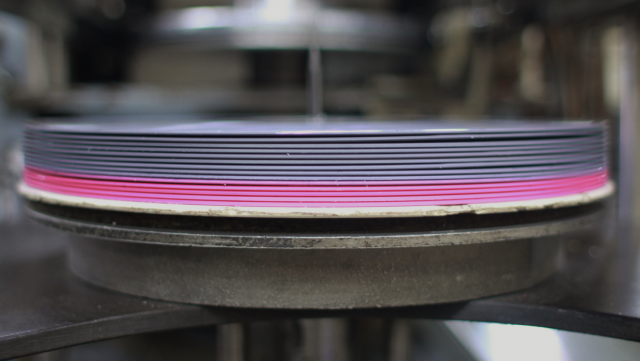

By the time the present location opened up on Bush Street in 1975, the space was installed with a floating floor and 136 speakers hanging above the audience and embedded into the walls and floors.

“What you are hearing in there is me at a board, changing and altering where the sound is coming from, the intensities, the speed in which it’s traveling,” says Shaff. “The board is an instrument of space. I am literally composing my work, which is on a hard disc in a separate part of the building that comes into the board and I then distribute it into the different speakers around the room.”

Today, with 176 speakers placed specifically around the custom made structure with slanted and protruding walls, the audience is carried into pitch-blackness, allowing no visual awareness, to hear a sequence of noises travel over and under and everywhere in between.

After nearly a half century, Shaff continues to show up every Friday and Saturday at eight o’clock to compose the performance for audiences young and old, both newcomers and returners looking for something new to expand their minds and views.

“With technology has come this world of sound,” said Shaff’s son and employee Dave. “The world used to be a lot quieter than it is now.”

Surround sound, Imax movie theatres, and the boundaries of music being broken down constantly have changed the way we think. Technology has pushed younger generations to crave new ways of thinking and to explore the unknown.

“People nowadays are searching out and looking for that experience with a kick and this is definitely that,” says Dave.

The performance at Audium is unique, no doubt. You are forced to see with your ears and accept the both harsh and delicate reverberations moving through you, transforming from distant clatter to in-your-face bangs.

“You can’t follow one thought for too long because the audio will take you somewhere else,” says Aaron Strick, twenty-four. “It was a nice blend of internal feelings that someone else is guiding and affecting. Its just a rare experience to have.”

Halfway through the performance the lights turn up just enough for your visual senses to return and for five minutes you and the strangers around you sit staring around at the dark images of each other’s bodies and the hanging speakers above you. For those that aren’t grasping or enjoying the composition, this is the time to exit.

“Initially we weren’t sure, and early on more people were uncomfortable with the darkness and the atmosphere,” Says Stan.

For now, Audium continues to use a recorded audio sequence in which Shaff changes every year to year and a half. But Shaff, his son, and McEachern have bigger plans for the future with more elements to add to the mix. Live performers and greater three-dimensional sounds are a hope for the staff.

Learning to use the soundboard is a daunting task, but one Stan plans to teach his son very soon. Dave, who has been around Audium his entire life and even lends to the performance with audio recordings of him as a child as part of the piece, plans to continue and expand further what his father has started.

“I look at Audium as being only a seedling, like a start up of the idea of space, immersion, sound movement and the control of that motion,” says Shaff. “I imagine it only getting more evolved and seeing more places like the Audium popping up eventually.”

You can experience Audium for yourself, every Friday and Saturday night beginning promptly at eight-thirty.