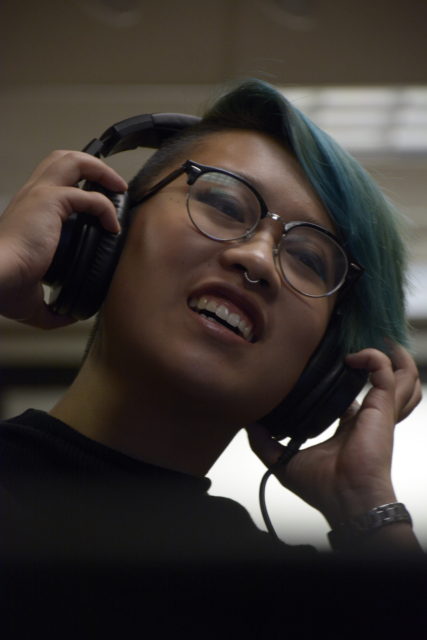

It is a typical Monday afternoon at the J. Paul Leonard Library at San Francisco State University. Busy—the kind of busy where booming conversations blend together until no actual sentences or distinct words can be comprehended. All the tables in the lobby are filled by people studying or conversing. Near the entrance sits an individual that sticks out from the bustling crowd.

Is it the brightly colored, a mix of teal and jade, undercut hair amongst a sea of brunette, blonde, and black hair? Or is it the chic business casual fashion style that makes one wonder whether this person is a student, a young professional, or a professor? Could it also be the confidence that exudes from this person that makes them stand out from the crowd of busy-bodies ambling along?

Jayde San Gabriel, an information systems major at SF State, sits with the kind of poise one often associates with businessmen—legs spread wide, strong posture, hands fiddling with a phone or tablet. Yet, there is a softness in their eyes that can only be described with one word: welcoming. Jayde’s temperament is somewhat contradictory to their mannerisms. Their gestures are composed, seemingly calculated, but in conversation they are energetic, bubbly, passionate, and constantly getting sidetracked.

“I am trans/non-binary. I have been semi-out almost two years now,” Jayde explains. They wipe their hands across their legs and comb back any untidy hair. “You can’t know someone is trans by just looking at them, or their gender expression, or what they are wearing, or how they talk. You’ve interacted with them and you just don’t know it.”

There is an excitement in Jayde’s voice as they talk about their love for lifting weights, taking care of over thirty varieties of succulents, fashion, art, photography, and video games, specifically Super Smash Bros. Melee. Jayde talks about themself with complete confidence and cohesiveness—as if they know exactly who they are—which is a feat not many in their early-twenties can honestly claim. There is a mix of masculinity and femininity about Jayde that amalgamates and transcends the binary of male and female.

After coming out as non-binary, they put their identity at the forefront of their interactions to push for more visibility and representation of people just like them. But they haven’t always been this self-assured. It has been a long and arduous journey for Jayde to come to terms with the fact that they have never felt comfortable with the idea of being boxed into one gender. Jayde struggled through conflicting ideas of whom they wanted to be versus who their mom and society wanted them to be.

“Growing up, I wouldn’t really say that I felt comfortable as a girl,” Jayde explains. “I was a kid—doing my own thing—I wanted to do a mix of feminine and masculine hobbies. But my mom, who is Chinese but raised in traditional Filipino culture, really pushed femininity on me, and anytime I would present or express myself as masculine I would get in trouble.”

Their mom wanted them to keep their hair long because they looked more feminine, but Jayde didn’t feel comfortable with it and only kept their hair long to abide by what their mom wanted.

“I started to confirm with what my mom wanted to see in me,” Jayde says. “In high school, I dressed more preppy. I hated it. I tried to convince myself that I liked it because my mom liked it.”

These early experiences lead Jayde to question their identity. It started with what Jayde calls as “queer rebellion,” where they came out as bisexual in high school because they found people, in general, were “hot.” To the disdain of their mom, Jayde also cut their hair shorter. It wasn’t until college when Jayde realized that their attraction to people was not the issue—the issue was that they didn’t feel content with being perceived as a woman or a man. Jayde simply didn’t align with those genders.

A close friend of Jayde’s, Derek Ching, recalls that Jayde has always been part of the queer community, and that it wasn’t a complete surprise to him when they came out as non-binary. He has seen Jayde mold themself completely into their identity.

“It was crazy how much research they were putting into it, but all the work they put into crafting their own identity came out nicely,” Ching says. “They have a really solid hold on who they are, how they identify, and what it means to them.”

Jen Reck, a cisgender female lecturer in sociology and sexuality studies at SF State, specializes in teaching and researching various discourses, topics, and issues on the LGBTQ community. Reck defines non-binary to mean someone who does not identify with the traditional parameters of male and female genders. They may identify as a mixture of those identities.

“When I was younger I never felt like a girl,” Jayde states. “I just felt like a person. Looking back now, I was just a non-binary kid who was socialized as female.”

According to Reck, gender dysphoria is historically a medical term that came about somewhere around the time of the emergence of transgender and transsexual identities back in the sixties. It was used as a diagnosis of someone who was transsexual. The term has evolved to be more of an expression of when people feel uncomfortable with the gender they are assigned at birth.

“People connect that dysphoria to a range of gendered practices,” Reck says. “Like being misgendered, having someone refer to you with a gender pronoun you don’t identify with.”

It was around Jayde’s sophomore year at SF State when they started feeling gender dysphoria when referred to as a woman.

“My body started to feel a lot of pain and dysphoria, where my chest would tighten up,” Jayde says as they clasp their hand to their chest. “Why would I get these hurt feelings whenever referred to as a woman or like she/her? This is kind of weird? Very weird.”

At that point in Jayde’s life, they started talking to gender therapists and doing research on transgender identity. Jayde says that there was a period of two months where they didn’t know who they were. Eventually, Jayde embraced their identity and became more comfortable with the idea of using they/them pronouns.

“If I don’t feel like a woman and I don’t feel like a man, I probably am non-binary,” Jayde recalls with a shrug. However, Jayde has not come out to their parents. They plan to wait until after they graduate to bring up the topic.

“I know that I have to come out to my parents at some point, definitely after I graduate,” Jayde says. “I have developed a battle plan, it’s still a rough draft though. My parents are religious, so I will have pamphlets from a nearby church supporting LGBTQ people and printed articles by more liberal pastors and how this is okay. Ideally, I would love to have a third-party to be like a moderator.”

For now, Jayde is happy to be able to accurately express and represent who they are, but they do face other issues when it comes to their gender identity.

Jayde met Emery Renner, their straight male partner, while playing Super Smash Bros. Renner says that he sees Jayde struggle with having to come out to people daily and yet still constantly be misgendered. Renner makes sure to reaffirm Jayde’s identity to support them.

“Just using the correct pronouns all the time in public,” Renner says. “And correcting people who are using the incorrect pronouns, even if Jayde isn’t there.”

Jayde is currently president of The Academy, a group at SF State that hosts regular Super Smash Bros. tournaments. The tournaments are very male-dominated, which is a fairly accurate representation of the general video game community.

Derek Ching—who met Jayde at one of these events—says that the issues they face as a non-binary person also show up in their gaming community.

“A lot of their struggles comes from the fact that they are in a very visible position,” Ching says. “As the president of the organization, they have to interact with a lot of people who are not familiar with anything queer or trans. There are a lot of experiences where Jayde’s identity isn’t respected, or who they are, and to an extent even the name they use.”

However, Jayde does not waver when confronted with these negative experiences. Instead, they take them as opportunities to promote their identity and push for more visibility and representation. Jayde says that being out and open as non-binary in such a niche community at least brings attention to it and brings the topic to people who don’t know about it.

“I started with telling people who I practiced with my pronouns,” Jayde says. “Then at our monthlies, I started to wear a nametag that had my name, my gamertag, and my pronouns. I started to make the font of my pronouns a little bit bigger each time.”

Reck says that learning people’s pronouns has a lot do with respecting the person and acknowledging who they are.

“Awareness leads to understanding, and understanding leads to compassion,” Renner says. “People who have hate or bigotry in them, it comes from a place of ignorance. So many people who hate trans people have never met a trans person.”

Jayde’s struggles and experiences have molded them into the confident person that they are today. They advocate for more visibility because they know how it feels to grow up not seeing anyone in media that accurately portrays who they are.

“Growing up, when I looked at kids shows or the news or online there was nobody that talked about being trans/non-binary,” Jayde explains. “There was no representation of people who don’t look conventional that was seen as normal.”

Jayde says that each transgender and non-binary person’s experience can be different from one another. There is no specific guideline on how to be trans or non-binary. Ultimately, it is up to the individual to define their own identity.