Editor’s Note: Following an editorial meeting, the staff concluded that the article’s reporting was inconsistent with newsroom standards. Any inquiries can be directed to us at [email protected].

Living with Dyslexia

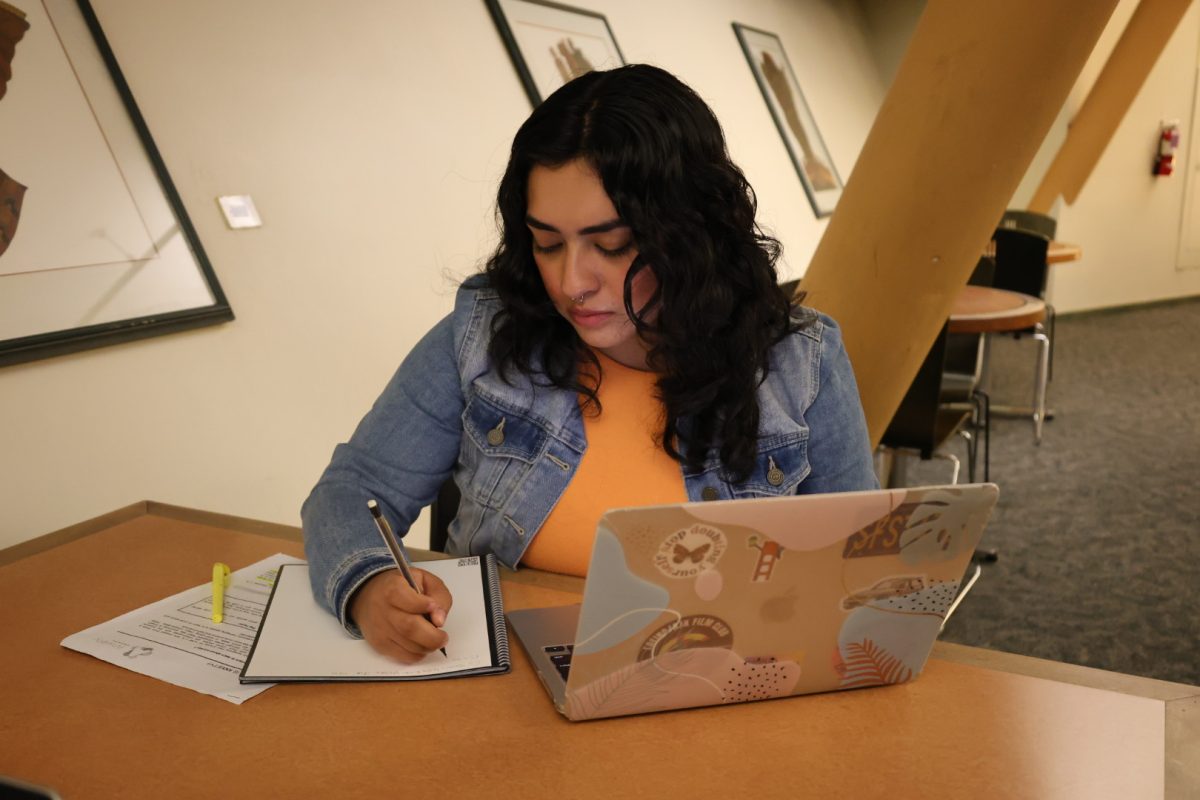

Kelly Rodriguez Murillo

•

December 8, 2018

More to Discover