It seems like some new movement comes up every week on social media. One day, it’s something harmless like people dancing to whatever song is the flavor of the month, another day someone in your mentions is talking about how millennials are extremely entitled, and then, you just see a post that seems somehow just weird. That post just seems more conspiratorial and paranoid, and it’s easy to just stare at it in disbelief, as this post might claim, for example, that vaccines cause autism. And then, it turns into the same sort of reasoning that eventually leads to more dangerous consequences. This is how fringe movements on social media become, well, not so fringe. And as these waves rise, how can they be regulated?

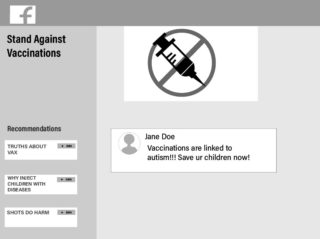

A recent measles outbreak in Oregon left fifty-three infected, and what’s worse, it’s ultimately the fault of dangerous rhetoric. Conspiracy movements such as the anti-vaccine movement rely on a variety of rhetorical tactics, establishing logical and emotional appeal in order to establish a sense of authority. These movements use Facebook and other social media platforms to gain a larger audience by establishing chat rooms that target potential converts, sharing faulty information without context.

“Most conspiracy theories rely on the idea that there is a secret knowledge that is being hidden from people intentionally, and there are people that have control over this information to maintain power,” said Orion Steele, an SF State Communications professor. “Most conspiracies I know tend to argue that it’s possible to manipulate information when you get from another source, and therefore the only reliable source of info is your own senses. If you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist. If you can’t hear it, it’s not real. That’s one of the main rhetorical strategies that most conspiracy theorists use to say the moon landing was faked, the earth is flat, or that vaccines cause autism.”

Another rhetorical strategy commonly used by these movements is also that they appeal to emotions, hoping that the evidence set forth isn’t questioned.

“They’re trying to differentiate communities.There’s a wide swath of political people saying we’re free and independent, that the government ‘shouldn’t get in our lives.’ The problem with all these movements is that they’re not based in science,” said John Ryan, a professor of Communications at SF State. “They don’t offer evidence. And if a student put forth a paper with that kind of evidence, they’d fail the class. It’s all pathos driven, trying to get you to feel something.”

In 2017, the Washington Post reported on a measles outbreak in Minneapolis among its Somali immigrant community that was a direct result of anti-vaccine groups. In this case, the Post reports that anti-vaccination activists repeatedly invited anti-vaccine movement founder Andrew Wakefield to talk to worried parents, especially in the Somali community about the view that vaccines cause autism in children. Wakefield is famously known for writing a paper in the Lancet journal which claimed that vaccines cause autism. His report has since been redacted.

The result of Wakefield’s targeted campaign coincided with a sharp decrease in Somali American vaccination rates, from ninety-two percent in 2004 all the way down to forty-two percent in 2014. The Minnesota Department of Health was able to show that anti-vaccine activists were able to take advantage of fears and faulty education regarding vaccination.

One of the arguments made by some anti-vaccine groups is that vaccines might not be necessary if you’re not sick. This reasoning eventually leads to other explanations that don’t accurately represent the problem and complicate it even further.

“Social media is a great equalizer of free speech, and it’s used a lot by people with many different points of view. It’s also a misunderstanding of how vaccines work. We have a biological substance that stimulates our own immune system unlike other medicines, such as antibiotics killing bacteria,” said Larry Vitale, a senior lecturer at Sf State’s School of Nursing. “Vaccines are different. They don’t kill anything, but they stimulate by alerting our immune system to a bacteria or a virus that will invade our system. What people don’t understand that there are sometimes preservatives and so they’ll make reference to a microscopic amount of some preservative and say that it shouldn’t be injected into a person. There are a ton of chemicals in our vaccines are very pure, but it’s really about the dose.”

That kind of logic can eventually lead to complacency, and that complacency can lead to further problems healthwise.

“It’s been said that when people fear the vaccine more than the disease, you have resistance. Once the fear of the disease subsides, the idea is why do we need to take them, the reason is that they’re not eradicated yet,” said Vitale. “Just last year in the Bay Area,there was a notable outbreak of measles, and it was amongst people who weren’t vaccinated a huge drain of public health resources to investigate this,and all of the person who were involved in the spread were those who could be vaccinated but weren’t.”

Even more dangerously, such movements might also be stepping stones to different, more dangerous ones. For example, Steele pointed out that the anti-vaccine movement is very different from ideological groups like the alt-right in what they want to achieve, but both engage their audiences and spread their messages through similar social media platforms. They both thrive on the lack of thought when it comes to new information and they both are predicated on a distrust in institutions.

“I think that a lack of education in critical thinking is what allows those ideas to flourish. The more people are exposed to those ideas without having the tools to challenge them understand why they’re flawed ideas, they spread like wildfires, whereas the goal of the alt-right is to accomplish white supremacy. And that is a very big distinction.”

One of the challenges compounding a lack of critical thinking is that social media platforms often let such content mostly go unchallenged while censoring other, more innocuous content. For example, Facebook tried to integrate Snopes into news feeds for certain articles in a short-lived partnership, while suggesting anti-vaccine content in search suggestions.

There’s also a thin, unclear line between censorship and regulation. In Sacramento, the ACLU’s Northern California chapter recently litigated a case arguing that Sacramento sheriff Scott Jones’ blocking of Black Lives Matter activists on Facebook was unconstitutional. In a statement, ACLU of Northern California Communications Director Brady Hirsch stated that the sheriff shouldn’t have blocked the activists due to the First Amendment, which “prevents governments from censoring people because of the content of their speech, their viewpoints or identities.”

Not all speech is protected, nor is all speech protected equally. Miriam Smith, associate professor of media law at SF State’s BECA department, teaches a class on electronic media and the First Amendment. Smith argues that while the line is fairly muddy for what constitutes censorship, there are a few distinctions. For most people, their social media accounts don’t constitute a public forum under the law, since places like Facebook and Twitter are private companies, whereas the ACLU argues that Jones’s account is a public forum.

Smith pointed to the case PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins, where it was ruled that shopping centers in California are technically public spaces with protected speech, after a group of students in southern California were told to leave a shopping mall for distributing pamphlets in support of a United Nations resolution against Zionism. In this case, a shopping mall is a privately owned place that is still ruled to be a public forum.

Even then, Smith still says that private companies have the responsibility under law to regulate speech in some capacity.

“It’s up to the private company, otherwise a regulation needs to be narrowly tailored.They can draw their own line and set their own standards,” Smith said. “It’s a judgement call and they’re under increasing pressure to stop call to violence, calls to terrorism, depictions of animal cruelty, child endangerment, and a lot of hate speech ordinances fail because they’re not narrowly tailored. It’s far easier since they’re not the government.”

Facebook did not respond to requests for comment.

So how can the onslaught of information on social media that allows such movements to flourish be fought against? Thinking about the source of your information is a good start, such as the place it comes from, the motivations behind the information gathered, and whether those sources are actually credible.

“For me, I teach that with sources. It’s not the information that needs to be seen first,I need to see where it’s coming from first,” Ryan said. “The problem is that we get used to ease and now we need to take the extra step: how do you know what you know. It takes more work. Anyone can publish a book, but I have to figure out who you are. What’s your agenda, where’d you go to school. There’s a lot less of that happening.”

Thinking about sourcing for fact-based information is a start, but it’s also not everything when it comes to thinking about the information we take in on a daily basis.

“A former teacher at SF State named Alexis Litzky told me one time that she named it everyday intellectualism: the willingness to go about your everyday with a critical eye, to evaluate the movies you watch, the music you listen to, the interpersonal interactions you have with other people, with a critical eye,” Steele said. “It’s no one activity or action or lesson plan in a classroom that’s magically going to solve these problems. We need to do everything that we can as a culture to encourage people to think about that stuff, to engage in critical thinking every minute of their life while they are conscious. Very few people engage in what Alexis calls everyday intellectualism.”