Culture Cannot Be Erased – A Central American Perspective

March 24, 2020

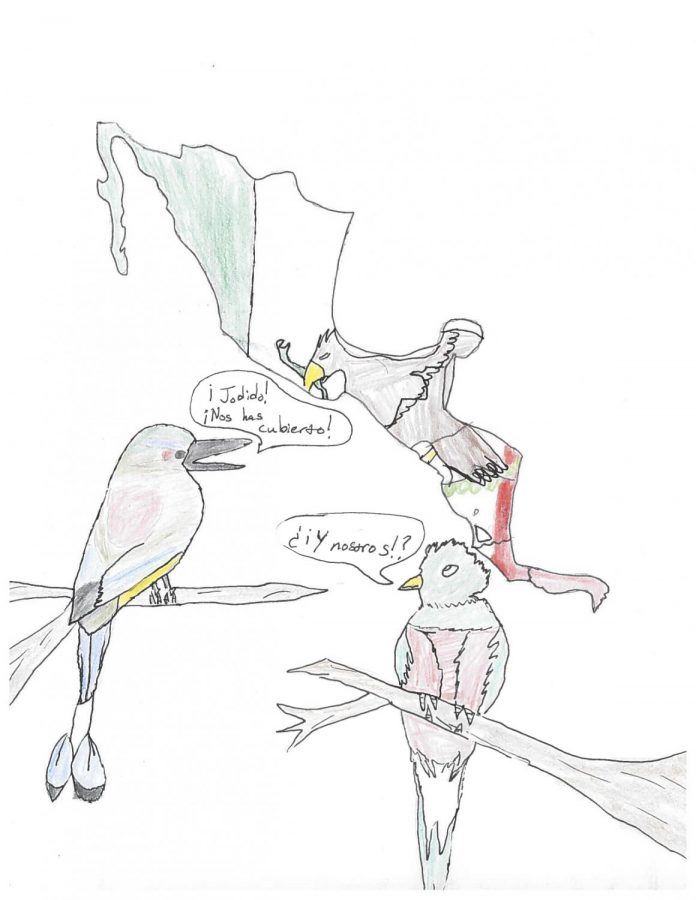

Scanning the sanguine walls, dripping with paraphernalia, it was easy to miss the Nicaraguan flag enamel pin and modest portrait of Guatemala’s national bird: the resplendent quetzal. They stood as the lone representatives of Central America on a predominantly Mexican wall.

Aurora Macha, member of the Latinx organization La Raza, commented in a slightly factitious, but serious tone, that there should be a portrait of Nicaraguan poet and revolutionary Daisy Zamora in the La Raza office.

Frequently being misidentified as Mexican is a rite of passage for Central Americans in the U.S. One might assume and perceive this as benign ignorance. Sadly this is not the case.

The ever-worsening political situation of Central America has resulted in more than 38,000 unaccompanied children and nearly 104,000 people migrating as families to the U.S.-Mexican border, according to a census report conducted by the Migration Policy Institute.

These migrants mainly originate from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras; with Guatemalans comprising 49% of those migrating as families. These three nations, also referred to as the “Northern Triangle,” have been experiencing high rates of gang violence and governmental instability.

Many within these communities, are now finding homes in predominantly Mexican neighborhoods and are now pushing for greater recognition of Central American achievement and artistic legacy. A fight against, what is often perceived by Americans, as the default Latinx experience.

Macha, who is of Nicaraguan and Guatemalan descent, said that the only time she had ever seen a Guatemalan in a major motion picture was for a fleeting comedic moment in the 2009 children’s film “Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.”

“It was the short dude who was like a cameraman … that’s the only representation that I remember as a kid. … Most of the media representation [of Latinx people],” Macha said, “is either Mexican or Puerto Rican.”

This Mexican-centric model has also historically had the unfortunate effect of propagating negative stereotypes and perceptions of Central Americans. Macha said, for the most part, not much else is allowed to surface to the top in terms of knowledge on Central American culture.

In Macha’s experience, the general Mexican perception of Central Americans is that they all “speak like sailors, that Guatemalans are all borrachos (drunks) and that Nicaraguans se creen (think highly of themselves).”

Local Chicanx social-rights activist, Adali Rodrigiuez, found themselves hard-pressed when asked how much knowledge concerning Central Americans existed within Mexican communities. They had a few moments of internal struggle before answering.

“We don’t really think about [Central Americans], you essentially don’t exist,” Rodrigiez said.

Mission-based artist Gabriela Aléman said this long-standing sense of cultural and linguistic isolation is often compounded by the difficulty involved in finding spaces or events that are geared toward Central Americans.

“It was the first time I had access to Nicaraguan culture arts in my life,” said Aléman, who is of Nicaraguan and El Salvadoran descent, on joining the Nicaraguan nonprofit cultural group “Chavalos de Aqui y de Alla,” (Children from Here and Over There) where she is now a board member and key figure.

“It’s been very transformative,” Aléman said. “It’s been very holistic and been very anchoring in my Nicaraguan identity. … I think that the Mission in particular doesn’t really center on non-Mexican or non-Chicano voices.”

Aléman, who describes her digitally produced art as being reactionary in nature, spoke of the necessity to humanize the Central American community through representation, artistic and otherwise.

“When people think of Central America or even now when they think of Nicaragua,” Aleman said. “They think of this really sad desolate country and we are so much more than that.”

An unfortunate and more than frequent byproduct of Mexican cultural hegemony is the loss of knowledge related to the cultural, intellectual and artistic achievements of Central Americans outside of the community’s direct influence.

Guatemalan poet, Liza Estrada, commented on the fact, with quiet frustration, that in many instances Mexican traditions are known internationally, leading to those unfamiliar with Central American traditions to try to understand Central Americans through the monolithic lens of Mexican values.

This is a growing phenomenon with more and more social nuance in the art world as the migrant crisis worsens. Estrada recounted an incident during a visit to the Chicago Art Museum.

The piece on display, an installation meant to honor the deaths of migrant children, had a profound impact on Estrada initially. Upon further inspection, Estrada discovered that the work did not make one mention of the children’s country of origin.

Estrada said the installation did not mention that these children were primarily Guatemalan and of indigenous origin. Their origin was left under the vague categorization of Latinx, ambiguously Mexican to those freshly arriving to the issue.

“These immigrant children are dying and people talk about it like it’s just happening to Mexico, when the reality is the majority of the people in there [are] from Central America,” Estrada said. “There is no specificity on the issue and doing so is harmful … a lot of folks will say, ‘we are all the same (Latinx people), you’re breaking us apart.’ And it’s like, no, we’re not. If you see that as separation because we’re finally focusing on Central Americans that’s a you issue.”

A relatively new group at SF State, known as Central Americans For Empowerment (C.A.F.E.), has been attempting to inform others on Central America, while simultaneously providing a conclave for Central Americans.

“We try to educate ourselves,” C.A.F.E.outreach coordinator Jose Vasquez said. “[To] educate others and empower them in a way that we can know about every different culture in Central America.”

The organization’s meetings usually revolve around a point of discussion, said Damaris Velazquez, C.A.F.E. ‘s president.

“Our topic [for Feb. 26] came about because we have been hearing, since the beginning, that there’s not enough Afro-Latinx representation in Latinx spaces,” Velazquez said. “Places maybe like La Raza or M.E.Ch.A. (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) or other historical organizations … don’t necessarily address the anti-blackness in our communities … so that’s usually how topics come about. It’s like what’s urgent? What do we really need to know about or discuss?”

Macha said, recently, La Raza has been attempting to combat and counteract the Mexican-centric manner of understanding Latin American culture.

“I know [La Raza] is seen as a Mexican organization. We’ve been trying to reset that for like the past two or three years. … [Members of La Raza have] been very accepting towards it,” Macha said. “Mainly because they know that it’s important to include all people in some way somehow, or at least more than just the Mexican-centric culture.”

Political turmoil combined with the phantasmagoria of online communities has allowed for a greater sense of solidarity and connectedness with relatives and issues in respective homelands.

Aléman, who publishes and distributes swarths of her work via Instagram, said social media often provides a news outlet for Central Americans that is not always available through conventional Latin American news outlets.

“It’s only because of the internet that we’ve ever been able to, meet each other, like know that we exist,” Aléman said.

Veleaquez elaborated on how being part of C.A.F.E. has afforded her the chance to feel the importance of community.

“It’s just very comforting, finally feeling accepted … not being ashamed of your own culture … like we can all finally say like, ‘hey, we have a place to be in.’”