First responders reflect on life-changing moment 19 years later

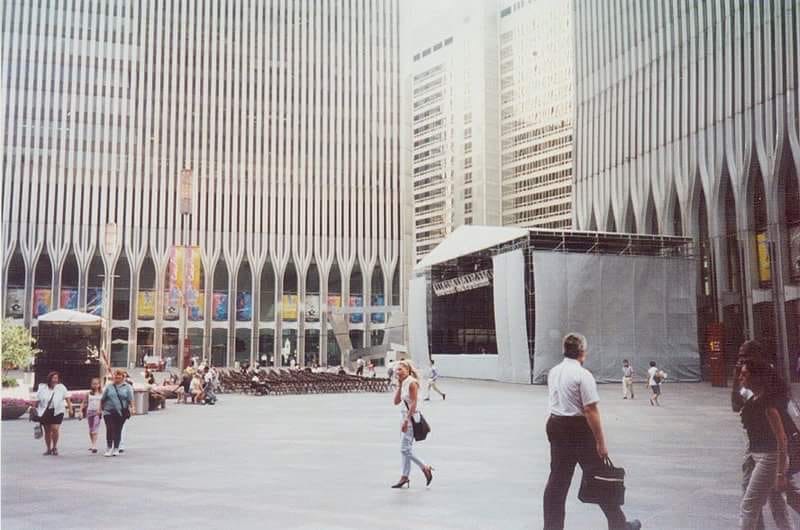

Photo courtesy of Jimmy Buckley

Jimmy Buckley’s truck, surrounded by debris, stood in front of the crumbling towers during theattacks on the World Trade Center. The truck was never found following the incident.

The day after two aircrafts flew into the World Trade Center, city officials in New York desperately called for any iron workers to help clean up the wreckage at ground zero. That same September morning, Jimmy Quinn, my uncle and hero, left his house in upstate New York with his hard hat and drove to what would later be considered a war zone.

Jimmy Quinn used plasma cutters to burn the twisted and mangled steel that was left after the twin towers came crumbling down. Because the iron was awfully disfigured, it produced pops of explosions as it reverted to its original shape. While cleaning up the debris and dismantled iron at ground zero, Jimmy Quinn saw hands and feet from the deceased. He saw the bodies of individuals who jumped from the towers hanging on the defaced bridge that once connected the Winter Garden Atrium and the World Trade Center. Firemen working at ground zero climbed up the demolished bridge to put corpses into body bags. After each body was retrieved, first responders paused for a moment of silence. They returned to work until the next body was retrieved.

One day, when Jimmy Quinn returned to ground zero with fellow iron workers and firemen to continue their work, an American flag was found within the debris. It was instantly mantled and raised.

Since the attacks on the World Trade Center, perceptions of mental health have changed drastically. Numerous first responders, victims and their families have admitted to experiencing emotional distress but are not using provided resources due to the stigma around mental illness. Others actively avoid the topic of 9/11 and its emotional aftermath.

“It does affect me emotionally when I think about it,” Jimmy Quinn said. “But I think I come from a generation that wouldn’t admit it.”

First responders were offered covered mental health screenings through the World Trade Center Health Program, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, due to the stigma around mental illness, many utilized the resources to evaluate their physical health, but neglected to assess their emotional stability.

Maureen Clancy, a therapist who volunteered for the World Trade Center Health Program, said the stigma surrounding mental illness in the past dissuaded first responders from accessing resources.

“It was stigmatized as a weakness,” Clancy said. “I think that’s why many first responders never sought treatment for mental health issues.”

Jimmy Quinn’s brother, Tommy Quinn, worked as a fireman in the Bronx during the attacks. He said he remembers many moments of feeling disbelief that day.

Tommy Quinn said he tries not to think about the attacks.

“I probably avoid it a little bit,” Tommy Quinn said.

Tommy Quinn recalled resting in bed on the morning of the attacks when his wife broke the news to him that one of the twin towers was on fire. Tommy Quinn, who was off of work, remained under the sheets as he listened to his wife describe what was on the TV screen. He initially thought the scene she distressed over was probably not that bad. Seconds later, he realized how serious the situation was when his wife commented on the copious amount of smoke escaping the north tower.

“The World Trade Center didn’t have windows that opened. They’re fixed in place, and it’s just a circulation system that they have throughout the building. You can’t open the windows,” Tommy Quinn said. “So when she said there was a lot of smoke coming from the building, it sort of dawned on me. I thought to myself, ‘Smoke coming from the building?’ So then I turned the TV on, and I went to see what was happening. And I knew right then, that it was really really really bad.”

Tommy Quinn reflected on his experience finding bodies months after the initial attacks and the heartbreak he felt discovering firemen’s uniforms while cleaning up wreckage. He said that if firemen weren’t working at their firehouses or on fires, then they were likely working on the aftermath of the fallen World Trade Center. On other days they attended funerals.

Danny O’Brien, another 9/11 rescue volunteer, experienced emotional trauma from the incident.

“In the beginning, it was hard to sleep,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien said that life following the attacks became nerve-wracking. He would catch himself constantly gazing up at the sky looking for airplanes. When he saw one, he would imagine what was going on inside. He often questioned whether planes he noticed were flying too low.

Jimmy Buckley, a retired stage producer, was setting up a stage in front of the north tower the morning of the attacks. He would soon become pinned under an outdoor staircase and trapped inside the lower levels of the south tower. Once above ground he fled the site through the streets of Manhattan.

Prior to the attacks, Buckley operated and took responsibility for the expenditures of multi-million dollar events. He said no stress he’d felt before could ever match the pressure and emotional impact he felt that day.

“I thought I was the strongest-minded person,” Buckley said. “This shook me to my core.”

Buckley spoke about his struggles with PTSD and emphasized the importance of mental health, which he previously considered malarkey.

He said he relives the attack everyday.

“PTSD is real,” Buckley said.

Vincent Rozalski, a San Francisco-based mental health professional who specializes in PTSD and trauma, said that society views mental illnesses much differently today than in the early 2000s.

“People seem to be more accepting of mental health problems as being legitimate. I think there’s been a lot of perception, and there still is some today, that if you’re having anxiety or depression or something else, then you’re just not strong enough to deal with it or you’re weak for having, you know, these kinds of issues,” Rozalski said. “I feel like that thought pattern has become less prevalent over time and more people are seeing it as a legitimate kind of medical condition that it is.”

Rozalski said that slowly over time, society is becoming more open to vulnerability. Stigma around mental illness is becoming less of a barrier for accessing treatment, he said.

Buckley also explained the outlook of mental illness from the generation he was born into and how that perception affected him before finding therapy.

“Our generation thinks ‘put it on the back burner and move on’,” Buckley said. “And it’s not that easy.”

He reflected on how therapy and treating his PTSD benefitted his well-being.

“Mental health [awareness] changed me because I’m still here,” Buckley said. “Without it, I wouldn’t have been.”

Ray • Oct 15, 2020 at 3:54 pm

Great article!