Saskia Hatvany (she/her) is the editor-in-chief of Xpress magazine. She is a freelance writer and photojournalist from Oakland, California. Her work has...

Carla Bayona poses with all of her clothes that contain a label listing fossil-fuel-derived fabrics in her San Francisco apartment on Oct 3, 2021. Polyester, polyamide, elastane, acrylic, and polypropylene are the most common fossil-fuel-derived textiles found in everyday clothing. (Saskia Hatvany / Xpress Magazine)

October 14, 2021

“It’s actually frightening,” said Jill Brandenburg as she glanced at the huge mound of colorful clothing overflowing from her son Jackson’s bed. Lucky for him, she wasn’t talking about the mess.

Like most people, when Brandenburg went shopping for clothes she hardly ever thought about what they were made of, so it came as a shock when she found out that most of her son’s clothing contained some form of plastic.

“I’ve never really paid attention to labels,” she said. “I do like linens and cotton, I mean, that’s for me, but for kids clothes, you just tend to gravitate towards what’s the most economical.”

Eleven-year-old Jackson Horton, Brandenburg’s son, hopes to be a professional actor one day and loves to dress up with his friends. He has an extensive collection of costumes in their Walnut Creek home.

“The costumes are plastic-y, I expected that. But for the regular clothes, I didn’t think it’d be as much,” said Horton. Like most kids, his wardrobe mostly consists of clothing from the Gap, Old Navy and Target.

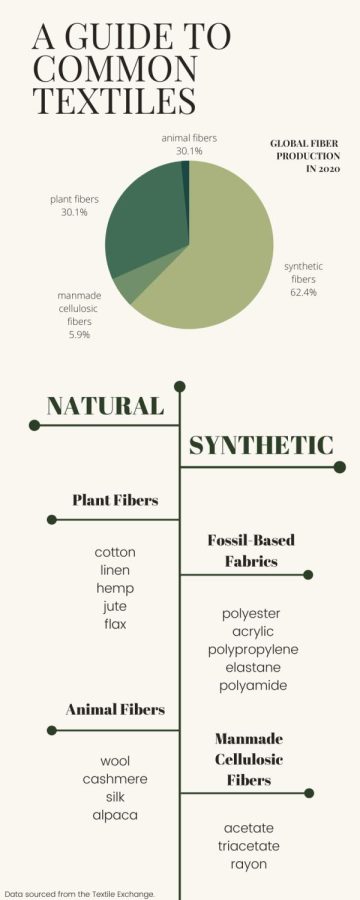

Nonetheless, plastic fibers are not reserved for cheap brands and children’s clothing. In 2020, over half of all global textiles produced came from fossil fuels, according to a report by the nonprofit organization Textile Exchange.

A quick browse of many major retailers’ websites reveals that it can be challenging to find clothing that doesn’t contain any form of fossil-fuel-derived fibers — even down to underwear. At Victoria’s Secret, the largest intimates retailer in the United States, of the over 400 different styles of women’s underwear available to purchase on the website, only three are completely devoid of synthetics.

Despite this, many consumers just aren’t that knowledgeable about textiles. This is partly because garments are usually made with a mix of different materials, weaving patterns and processing techniques, making it almost impossible to tell what a garment is made of just by the look and feel. Instead, consumers have to refer to a composition tag, which contains laundering instructions and is often hidden in the seam of their clothing. This list of materials can sometimes be extensive and contain vague and unfamiliar terms to the average consumer.

Fabrics derived from fossil fuels alone fall under as many as five different categories: polyester, polyamide, acrylic, polypropylene and elastane.

Polyester, which is found in everything from underwear to outerwear to t-shirts, accounted for 52% of all global textile production in 2020, according to the Textile Exchange report. Nylon, part of a group of fabrics called polyamide, is routinely used for lingerie and bathing suits. Acrylic is often spun into plastic “wool” and is commonly found in knitwear. Elastane is used for stretch and is now found in most denim blends, while polypropylene is often found in accessories and footwear.

To make matters more confusing, one type of textile can have several different names. Spandex, Lycra, Numa, Spandelle and Vyrene, are all just trademarked versions of elastane.

Even the term “synthetic” can be misleading. Rayon, a category of fabric made from wood pulp, is sometimes called a semi-synthetic because the textile requires the use of harsh chemicals and extreme processing.

Sadie Battle, a 26-year-old who works at an accounting firm in San Francisco, said that she wasn’t aware that denim was made of cotton, much less that her clothes had plastic in them.

“It’s not something that I pay attention to to find clothes. I guess I’m just checking more if it fits on my body. I’m not really looking at what it’s made of,” said Battle, who usually shops online where fabric composition is not always advertised.

Battle knew that some of her clothes were cheaply made, but she didn’t know that they actually contained plastic fibers that could be shed into the environment.

Battle is not alone. A 2020 study by the Nature Conservancy found that over 57% of consumers had no knowledge of microplastic pollution and that 50% who did had learned about the issue in the last year.

Carla Bayona, a San Francisco photographer who likes to shop for secondhand clothing, said she never thought to look at the composition labels on her clothing, even though she had heard about plastic microfibers before.

“I didn’t realize how much of it I have,” said Bayona.

Tiny plastic fragments called microfibers, many completely invisible to the naked eye, have been found in some of the most remote places on earth, including the Arctic, the deepest point of the ocean, and on the summit of Mount Everest.

While it’s unclear how much of microfibers come from atmospheric pollution, the Nature Conservancy study estimates that about 35% of the microfibers in the ocean come straight from our washing machines and that a single garment could release hundreds of thousands of fibers per wash.

Significant amounts of microfibers have also been found inside people’s homes and lungs. One study from the University of Plymouth found that people were more likely to be exposed to microplastics in the air during a meal in their home than by ingesting mussels contaminated with microplastics.

“When you sit in your room at home, and you look at the dust flying in the air with the sunlight shining through, a lot of that is fibers from just general use,” said Krystle Moody-Wood, founder of sustainable textile consulting company Materevolve.

The health implications of ingesting these fibers remain unclear, although several chemicals involved in the processing of textiles are known to be harmful to human health.

Outdoor recreation brands like The North Face and Patagonia have pledged to stop using perfluorochemicals (PFC) and polyfluoroalkyls (PFAS) in their clothing after they were found to be harmful to human health. PFAS and PFCs are often used to add waterproof or stain repellent properties to fibers.

Moody-Wood, who spent three years working in advanced materials research for the North Face, said that once microplastics are in the environment, they can both carry and attract chemicals like PFAS — even if the chemicals originally come from other pollutants like flame-retardants.

Even natural fibers like cotton are often treated with a long list of chemicals in order to make them suitable for wearing. Phthalates, which can be harmful to infant development, have been found in a range of textiles including infant cotton clothing, according to a 2019 study conducted in China.

“As it stands today cotton is a terrible industry, as well as much other food and chemical agriculture,” said Moody-Wood. “We’re adding fossil fuel-based dyes, we’re adding water repellents, we’re adding all these chemistries that change the way that materials would live in the environment.”

Some companies have started developing bio-based synthetics. Lycra has patented a form of elastane made of 70% content derived from corn. However, there is yet to be a replacement for fossil fuel-based fabrics as they are currently used.

“In my previous career, we were looking at chemistry we could add to the polyester to make it feel cooling or make it feel more comfortable, or anti-odor,” said Moody-Wood. “And it’s like, well, here we have a bunch of natural materials that do that on their own.”

When buying new clothes, she recommends looking for natural fibers like cotton, linen, wool, silk, cashmere, hemp and jute. Moody-Wood said there is no “silver bullet,” but that long-term and secondhand shopping is the best way to reduce individual environmental impact.

To date, hardly any legislative action has addressed microfiber pollution and the prevalence of synthetic fabrics, partly because the full scope of the implications are unclear, and partly because a lack of public awareness also means a lack of public pressure on governments.

Materevolve is currently working on a report about microfiber pollution in tandem with the United States Environmental Protection Agency. The report will be presented to the United States Congress in 2022 and will include federal recommendations.

“Overall, it’s been a huge eye-opener to me,” said Brandenburg. “It’s gonna make me a little bit more aware of what choices I’m making when it comes to clothes.”

Saskia Hatvany (she/her) is the editor-in-chief of Xpress magazine. She is a freelance writer and photojournalist from Oakland, California. Her work has...