Em (they/them) is a journalism student minoring in American Indian Studies. They enjoy writing about astrology, music, cooking and books. In their...

May 13, 2022

When Gordon Nipper had his first exposure to sex education, he was in the fifth grade. Even at the time, he didn’t feel that what he was learning applied to him. It was the experience itself that had a lasting impression on him rather than the information.

“I knew I was gay since second grade, so I was like, ‘This isn’t applying to me. I do not care about this,” Nipper said. He added that examples of queer sex were not discussed. “But that was obviously not shown because we live in a very heteronormative society that just pushes straight sex, straight ideology onto us.”

He remembered one day, in particular, the class was broken into groups of boys and girls who had to create presentations on sexual health. As a result, Nipper was separated from his friends, who were all girls, which made him feel isolated.

In California, most sex education curricula are not as inclusive as they should be. A study published in the medical journal BMJ Open, which addresses questions in medicine, public health and epidemiology, analyzed 5,656 English-language records used by sexual education facilitators. The study found that from January 1990 to May 2021, only 24 records met the criteria of being LGBTI+ inclusive. Queer inclusivity in this context means sexual health education for same-sex relationships, terminology, aspects of identity and direction to services. This is in addition to providing education on sexual orientation, gender identity, holistic approaches to romantic relationships, love and communication.

Helen Everbach had her first exposure to sex education when she was in the first grade, where she learned about the reproductive system, pregnancy and childbirth. This early education also included information about appropriate and inappropriate touching. In the fourth and later on in the eighth grade, she learned about puberty, sexual health and sexual orientation — including the existence of trans and non-binary people.

Everbach was given this education through her Unitarian Universalist church in the Philadelphia suburbs under a program called Our Whole Lives. At the time, she was a public school student and said the OWL program allowed her to answer a lot of the questions her peers were having concerning their bodies and sex. During high school, she was often drawing vulvas on the walls and pointing out the details of its sub-anatomy.

Everbach, a graduate student, felt that her sexual education primed her to become the director of the Education and Referral Organization for Sexuality at San Francisco State University.

When speaking to queer students at SF State, Everbach said she had noticed queer students’ mixed experiences with their childhood sexual education. She added that where school education has fallen short, students have had to resort to finding information from alternative sources.

Lux Montes, the assistant director of the Queer and Trans Resource Center at SF State, who identifies as non-binary and queer, said their sex education left them feeling alone.

“It definitely made me feel ashamed and embarrassed, like my form of sexuality was wrong or non-normative because there are no instances of representation of it,” Montes said.

Montes’ shortcomings with their sexual education led them to search for resources online. They grew up in a very traditional Mexican household, where gender and sexuality were not discussed but strictly defined. Seeking perspectives from other people online gave Montes more confidence in discovering their identity. They said that if they did not have online resources, they would be left to their own devices without any idea about queer sex or identity.

“If I was left in that place, I feel like I would not have become who I was or have a real hard time becoming who I was,” said Montes.

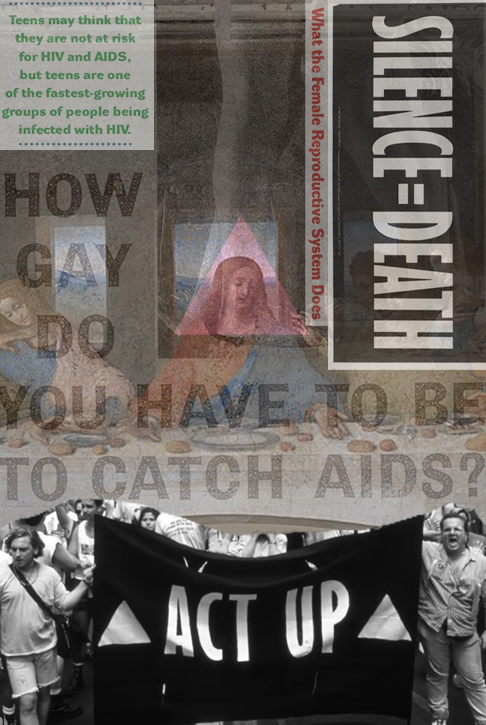

Turning to online resources is a common approach for queer people seeking sexual education outside of school and family. According to research by the Gay Lesbian & Straight Education Network, 62% of queer youth searched for sexuality or sexual attraction information online; by contrast, 12% of non-queer youth searched the same topics. The study also found that queer youth searched for health or medical information and resources about HIV/AIDS and STIs, all at rates significantly higher than their peers.

DeMorié Robinson, who is gay, said their abstinence-only sexual education — which teaches students not to have sex — left them wanting more comprehensive information.

“I just did my own personal research about how to actually have safe gay sex and the different types of ways to have sex — not just homosexuals but also with lesbians and everyone else,” Robinson said. “[The internet] has really been a big help; I started out watching gay YouTubers describe sex and how they have it in their own safe ways.”

Ilana Slavit, a non-binary sex educator and student at the Institute for Sexuality Education and Enlightenment, said they have mixed feelings about using the internet as a tool for sexual education.

“[It’s] a great resource, but it can also be damaging because there’s a lot of not accurate information on the internet,” Slavit said. “That’s why it’s super important that in sex education, we offer additional resources.”

Montes said that sometimes the internet could give a deceptive picture that may not always apply to all queer people. They said when they were looking for information on various websites, what they saw was extremely fetishized. Montes felt that being exposed to such content was not healthy when they were first stepping into and learning about their identity and sexuality.

Queer individuals like Nipper had a lot of influence from people in their life, such as friends and classmates who shaped their sex education. He said most of his knowledge came from the people around him rather than school or his parents.

“I had a lot of older friends who were having sex and watching porn and stuff. So I was introduced to porn and sex at a very young age, like a harmful young age,” Nipper said. “I could not go to my family for any of those questions like that.”

Everbach also had experiences with friends who introduced her to more parts of her own queer identity. At a Unitarian Universalist summer camp during the summer of her sixth-grade year, she met other queer people her age — also students of the OWL sex-ed program — to who she could relate on many levels.

“There were queer people at my church, but Unitarian Universalism skews older. There’s a lot of old, middle-aged couples, which I didn’t really relate to as a young person,” Everbach recalled. “But I met a bunch of young queer people with funky hair.”

At SF State, there are a variety of programs designed to be of benefit to queer students. For example, EROS has events such as Queer & Trans Sex Education, Queer Erotic Book Club, and Sex, Dysphoria & Transition. EROS also has a lot of materials for queer students to learn from, including books and other materials about sex, gender identity and sexuality.

“We also have drop-in hours where students can just drop in and talk to me about sexuality, dating, intimacy, gender, all kinds of things if they have questions or just want to process through something or get advice or just hang out with us,” Everbach said.

Beyond these dedicated resources, queer students such as Robinson have been able to explore themselves and their identities through classes at SF State. Robinson described a Health and Promotion class that helped them dive into different sexualities, different types of people and different gender identities.

“I guess that propelled me to do my own research and find out that I don’t have to just stay in this identity, I don’t have to conform to this simple identity that society has had, a very antiquated type of ideology,” Robinson said. “I could just be me.”

Em (they/them) is a journalism student minoring in American Indian Studies. They enjoy writing about astrology, music, cooking and books. In their...