Out of the Picture?

Film photography fights to stay in the light in a digital world.

Josh Nero holds a sheet of negatives up to the light in his apartment on campus during a portrait session on Nov. 3, 2022. Nero, a third-year student, has shot film for years, and hopes to make a career out of film photography. (Juliana Yamada / Xpress Magazine)

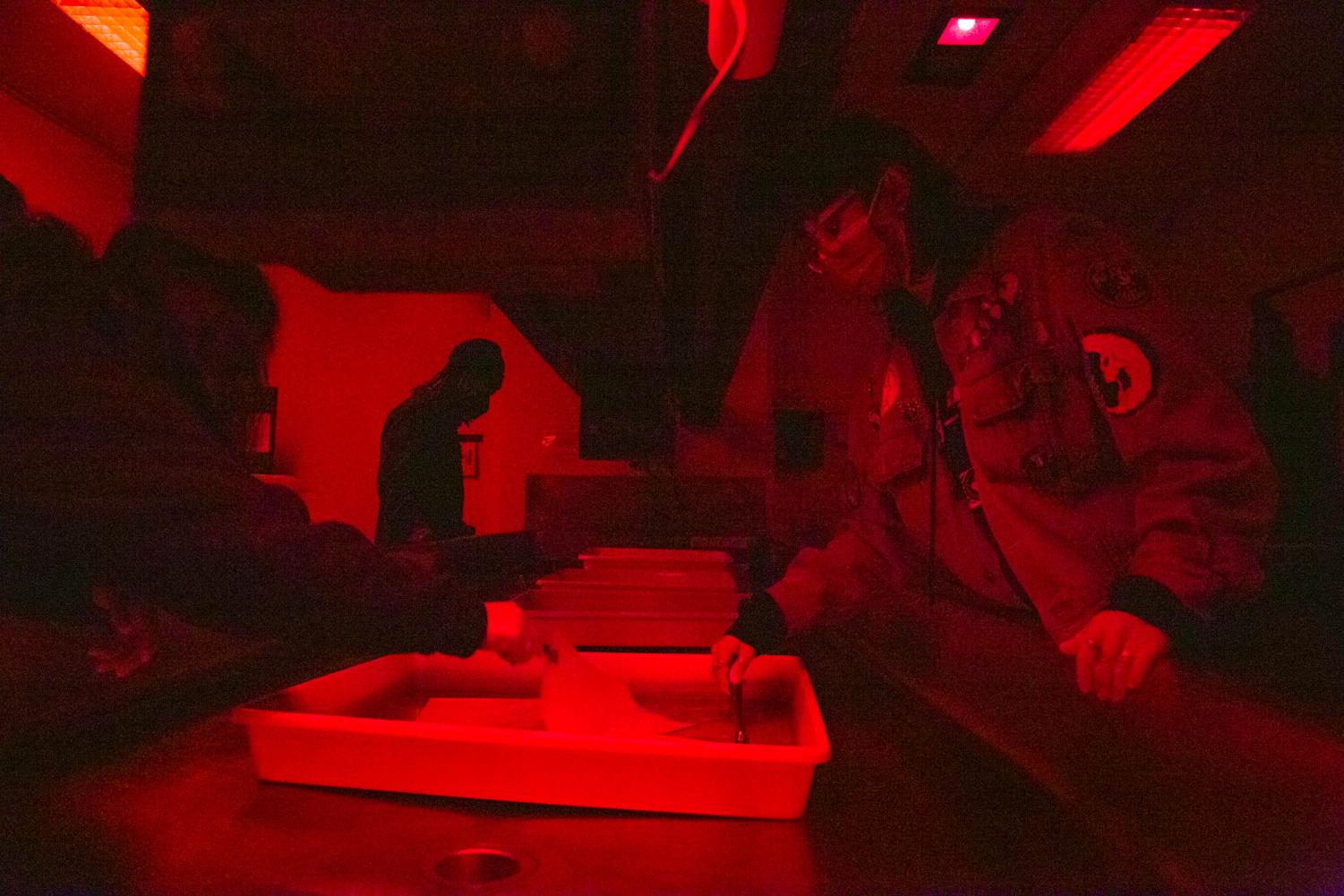

As one steps into the void, their eyes narrow to help adjust to the darkness. The pitch black gives way to a martian red. A dank, metallic smell of chemicals strikes the back of their nose. The sounds of paper sliding across workstations, old mechanical switches flipping on and splashing of liquid-filled trays permeate the air. As the room finally comes into focus, the precautionary hand that was once slightly in front of them to keep them from blindly bumping into something lowers, and they realize they’ve entered a darkroom.

In a world that’s gone digital, analog mediums have been replaced by faster, less messy and more efficient alternatives. Film was once considered a dying medium, but with increasingly rare supplies becoming more expensive, photographers find ways to make ends meet. As film fights to stay in the light, analog enthusiasts breathe life back into the medium. New hobbyists and artists have kept film from becoming a forgotten relic.

“Everyone’s either digging out their old film cameras, or a lot of younger people are just getting into it for the first time,” said Matt Osborne, owner of Glass Key Photo in San Francisco.

Film may be considered antiquated, but that doesn’t mean it’s lost its charm. Many still find joy in developing film, and appreciate the artistry behind the chemistry.

“I enjoy this [film photography] a lot…the process of it,” said Joshua Charles Nero, a third-year student at SF State.

Nero wants to continue working with photography after graduating.

“I love the battle between uncertainty and trust that goes into shooting film,” said Nero. “Not knowing what an image looks like until you develop it.”

Nero, who has roots in Louisiana, remembers where his passion for the medium began. Traveling between California and Louisiana in his childhood exposed him to a wide variety of lifestyles, sparking his interest in taking pictures. As he got older, his photography evolved from landscapes to portraits.

“Being able to capture images for artists and brands on a consistent basis is one of my main goals,” said Nero.

His dream would be to open a creative studio to showcase his work and the work of other talented artists that look like him.

Angela Berry, a photography professor at SF State, said the darkroom is “the point where science and art combine…it’s pretty much a chemistry lab.”

Berry, who just began teaching at SF State, loves the sensorial experience that is film photography. She has worked with her own photographs, taken with her phone, and made digital negatives processed by platinum palladium or gum bichromate — effectively bringing digital back into the analog process.

One of the first cameras Berry has shot with, and still uses today, is a Hasselblad 500cm — a classic, square-format Swedish camera with a vertical viewfinder usually held at chest or hip level. Berry originally went to school for writing, but loved visual and sound arts growing up. In college, she made a switch and majored in painting, but a study abroad program in Berlin with a camera around her neck brought the transformation full-circle.

Berry’s relationship with film photography runs hand-in-hand with her perspective on visual arts.

“It’s narrative and anti-narrative at the same time — it’s explicit and ambiguous, it’s a fragment of something, but it’s not the whole thing,” said Berry.

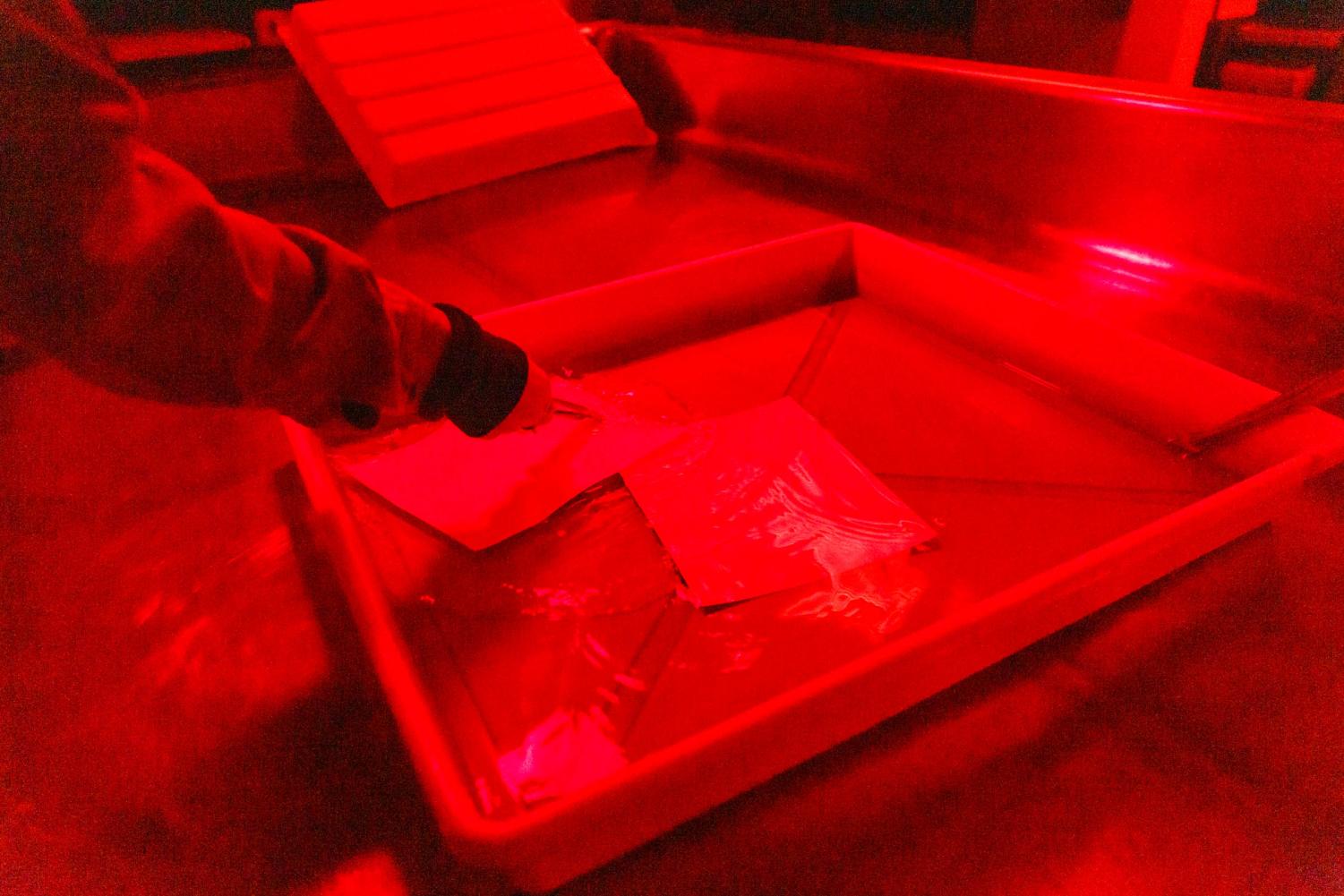

Film photography has the ability of being a medium that is malleable, able to change to the bend and flow with every artist. Maybe that’s the allure — the beauty of creation, of seeing a moment become reality. It can feel a little supernatural, to dip a white, gelatin-covered paper into a solution and watch rich-black tones grow deeper and white highlights create detail. A test strip becomes a guessing game in a way, moving closer to figure out the photo, squinting to discern between subject or background.

However, with a medium like film, supplies have become difficult to come by – especially in mass quantities, due to how expensive they are. Film cameras and supplies that were once at rock-bottom prices have skyrocketed. “We sell a film called Kodak Portra 400, which is normally $15 a roll — that’s now $40 a roll,” said Kevin Jordan, an employee at Looking Glass Photo in Berkeley.

With film photography, a common element that most point to as their favorite aspect of the medium is the time, technicality and process of composing an image.

“It’s a different shooting experience. You have a finite amount of photos you can take which changes your mindset and thought process,” said Jordan.

Film requires the photographer to be more careful and meticulous. Artists approach the process at a slower pace, which causes more thoughtfulness in regards to what and how they’re shooting. Whereas with digital, they can kind of “spray and pray” according to Jordan. Film is the opposite. It makes the photographer slow down.

Nero begins the process by making test strips of the image. This saves time and paper, and reveals enough of the image to discern whether or not the photograph needs more or less time exposed to light by the enlarger. Time is also key in the development process. Nero places a strip beneath the enlarger, flips a switch and waits several seconds for the enlargers beam to switch off.

After repeating the process at different lengths of time, each strip can now be placed into the developer solution. The solution bath portion of the development process has three main parts; developer, a water or stop bath and fixer. Placing his strips into the developer bath tray, Nero agitates the test strip by gently shaking it as it’s submerged in the sulfite solution.

Silver halides are converted into silver metal, making the invisible, visible. The pale-colored silver halides are then converted into black-silver metal, leaving an image created by the contrast between black and white.

The process of developing film is a time and labor-intensive journey that requires patience, a bit of chemistry and several tools focused to create a single composition. The necessity for a room that offers a slight bit of sensory deprivation seems serendipitous.

Darkrooms have been used to process photographic film since the medium’s inception. Even before cameras were invented, the ability to create an image from light was only possible in a room free of any other sources of light except from one precise point: a camera obscura.

Records date the invention of the obscura at around 400 B.C., which was little more than a simple room with a small hole on one side and a cloth draped on the opposite. When a darkroom is created with the correct light conditions, an inverted image will naturally be cast onto the opposing wall. As time went on, the room was downsized into a more manageable, box-like device, becoming some of the first pinhole cameras. These devices would eventually lay the foundation for what we know today as a modern camera.

Photosensitive silver-nitrate is the key chemical in creating an image. This material allows light to essentially burn an image onto a surface. Older ‘prints’ would have been created on paper, but were faint and temporary. Paper was replaced by glass, glass by metal and metal by celluloid — or what is now called film. The chemical process has evolved, but remains largely similar to those of the past.

Even today, the modern photosensitive process requires the use of a room that blocks out all other light that would threaten the development of the film. Chemicals like hydroquinone, acetic acid and sodium sulfate are some of the culprits responsible for giving darkrooms their pungent smell. These ingredients are found in most photo developers, and are toxic if not used in safe, ventilated conditions.

For as much joy as the medium brings to those interested in it, scrounging for materials can burn a hole in their pocket. “It’s definitely been rough,” said Osborne. “Fuji has not produced film since pre-COVID and Kodak was having supply chain issues like crazy…feast or famine, really.”

With people looking for things that they could do outside, creative outlets that were once tossed aside as too time-consuming suddenly found a purpose. Those that may have not previously had time for the art found some during quarantine.

As frustrating as supply issues may be, they aren’t enough to keep enthusiasts away from film.

“You have to learn to work with what you’ve got — to troubleshoot,” said Berry. “In any art medium, problem solving is a really empowering skill set.” The ability to make your work in any conditions and to adapt — these are some of the values that film photography has the ability to develop.

Geri • Dec 5, 2022 at 4:58 pm

Amazing!