The Lion’s Stretch

Mountain lions fight to survive amidst increasing threats against them and their habitat.

In the early dawn hours, a mountain lion sits on the hilltop of Andy Forward’s backyard. She seems relaxed as she turns her head, taking in her surroundings with big eyes. Her ears perk up occasionally and she tilts her head upward, sniffing the air. There doesn’t seem to be any sense of urgency — on the contrary, she lets out a wide yawn as she continues to glance around. The lion slowly gets up, and with a nimble grace, she climbs up onto a branch of a nearby tree, her long tail dragging on the ground beneath her. She stills completely as she stares out at the horizon. Suddenly she turns around, leaping up onto a higher branch out of view and then dropping back to the ground and into frame. She pads away, and the footage ends.

That moment was captured by the one of many cameras Forward has set up around his remote Pacifica property in the mountains. Forward installed them around three years ago, after seeing a few mountain lions around his property. Through his monitoring, he realized it was only one female mountain lion he was seeing, distinguishable by the markings on her face.

Forward has no background in studying pumas or biology — he just finds mountain lions fascinating.

“There’s something remarkably majestic about them when you see them in the wild. Even if you’ve had cats, you kind of know the movements and things, but then it’s on a much bigger scale.”

Mountain lions face a dangerous existence throughout California, including the Bay Area. They are hit by cars, legally hunted with permits and forced to inbreed due to genetic isolation. In 2019, the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned for mountain lions to be classified as an endangered species, writing that future human development in the Bay Area “is anticipated to further fragment habitat” and “increase threats to their survival.” In 2020, mountain lions were granted temporary endangered status. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife will soon decide whether to make it permanent.

Mountain lions — also known as pumas, panthers, cougars or catamounts — are “like nature’s gardener,” explained Zara McDonald, researcher and founder of the Bay Area Puma Project (BAPP). As a keystone species, they help create the necessary conditions for other plants and animals to thrive.

“They influence every aspect of the habitat and other wildlife. Just by killing a deer, they feed a medley of other wildlife — all kinds of species, from ovules, to birds, to small mammals to insects,“ McDonald said.

The benefits aren’t just limited to nature either — mountain lions help humans too.

“They keep disease out of the system, because they feed on weakened and disease prey first. They keep systems clean and robust,” McDonald said.

According to McDonald, reducing disease in ecosystems lowers the chance of zoonotic spillovers such as COVID-19, in which animal diseases transfer to humans.

McDonald created the BAPP in 2007, after she encountered a puma while out trail running and was intrigued. She started focusing more of her research as a biologist into the species and realized how little the general public knew about them. The BAPP now promotes conservation through research and education.

No exact count exists of how many mountain lions call California home, making it difficult to track any changes in population over time. The most recent count, published by Fish and Wildlife in 1996, estimated there were between 4,000 to 6,000 lions living in California. Fish and Wildlife says they are working on a new count.

Urbanization threatens mountain lions the same way it does for much of other wildlife: by invading their homes. But pumas are distinct in the amount of habitat they require. The home territories are the largest of any land mammal in the Americas, ranging from 30 to 125 square miles, according to the Humane Society.

According to the National Wildlife Federation, that’s “about 13 times as much area as black bears or 40 times as much area for a bobcat.” Mountain lions, particularly the males, are also highly territorial, leading to low population density. There aren’t many mountain lions living in a given area, and they require large amounts of land to roam and find mates.

That need for space becomes a problem when humans have built on their land. Highways, in particular, are a lethal obstacle course for mountain lions, dividing their habitat up.

McDonald said that around 130 mountain lions are killed per year in California while trying to cross roads. The damage doesn’t just stop at that one mountain lion killed, though. It also has a ripple effect on future generations.

With males unable to cross into particular areas to find females to mate with, certain areas become “genetic islands,” as McDonald dubs them. The mountain lion population subsequently dwindles, and the only mating option becomes inbreeding, which leads to birth defects and hurts the long-term survival of the species.

In Southern California, researchers have already begun to find signs of inbreeding among mountain lion populations. A 2022 study out of UCLA found a 93% rate of abnormal sperm among five male mountain lions. According to McDonald, Bay Area researchers are also beginning to see signs of declining genetic diversity and inbreeding.

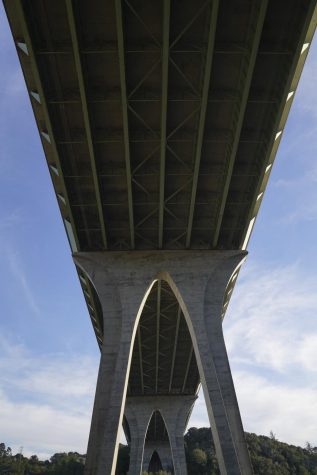

Wildlife crossings — overpasses or underpasses across highways explicitly designed for use by animals — potentially provide a solution. They can reconnect genetic islands with the land, allowing mountain lions easier access to parts of their habitat and thus reducing inbreeding.

In Southern California — specifically, Agoura Hills, which lies just outside Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley — construction began this year on what supporters call the world’s largest animal crossing, costing around $90 million. It aims to save the mountain lion population in the Santa Monica Mountains, a range isolated from the rest of the natural habitat by heavy human development, such as the massive 101 and 405 freeways. This isolation has led to the number of mountain lions declining rapidly, and many of them resort to inbreeding. Mountain lions are at risk of disappearing altogether from the Santa Monica Mountains.

A more practical and direct benefit of wildlife crossings is the reduction the amount of roadkill on highways, according to David Stoner. He’s a professor at Utah State University, and has worked on research into mountain lions with McDonald. Utah has built several wildlife crossings that have been successful for both wildlife and humans.

“Animals can get onto the highway, but it’s reduced dramatically,” Stoner said. “It conserves animals — the public is concerned about that — it also reduces human injury and property damage. That’s the winning combination.”

If wildlife crossings can reduce roadkill, one area in the Bay Area seems like a perfect candidate for one.

In a 2021 study, the Road Ecology Center of UC Davis found the portion of Interstate 280 between Cupertino and San Bruno to be the deadliest for wildlife in the entire state. Wouldn’t that make it a perfect candidate for a wildlife crossing?

According to scientists, no.

“When people bring that up as an area to enable more crossing, I’m always like, ‘Listen, you really don’t want to do that,’” said McDonald.

Not all places make for good wildlife crossings, McDonald explained. It depends on the two sides of the highway being connected. A crossing only works well if there are two good chunks of habitats for wildlife on both sides.

For much of the Cupertino-to-San-Bruno stretch, the highway flanks the Crystal Springs Reservoir to the west. That name might not stand out, but most drivers would know it when they see it. The lush, green hills of the Santa Cruz mountains suddenly give way to a pristine, blue lake, with a freeway exit seemingly the only sign of human development.

Much of the Eastern side contains only residential neighborhoods. It’s a stark contrast in terms of livability for wildlife. While animals in Crystal Springs Reservoir can wander freely with almost no human contact, the other side is a minefield of urbanization.

Because of that, McDonald said, it would actually be best to keep mountain lions and other wildlife in the Crystal Springs side from reaching the other side at all. A separate report from the Road Ecology Center recommended Caltrans put up more fencing and strips in an effort to deter wildlife from crossing.

Wildlife crossings are better in places in the Bay Area like Highway 17, McDonald said. There, four lanes of bustling traffic barricade mountain lions on either side.

“There was a male and female that crossed regularly to mate, and she got hit the day before she was going to give birth,” said McDonald.

In 2022, construction started on a 90-foot, $12.5 million underpass after 12 years of campaigning.

But McDonald said that mountain lions killed by freeways are “only part of it.” Pumas are also legally hunted via depredation permits — permits issued by Fish and Wildlife and obtained by homeowners who claim a lion has caused significant damage to their property. According to their data, Fish and Wildlife issued 246 depredation permits in 2020, and 50 mountain lions were killed using them.

Mountain lions sometimes receive less-than-warm welcomes from neighborhoods because people fear for their children or pets. Forward said his neighbors’ reactions to mountain lion sightings reported on sites like Nextdoor have been mixed.

“On the whole, I would say, in about the three years I’ve been monitoring them, the public perception has changed from being somewhat alarmist to being a lot more positive,” Forward said.

The BAPP educates homeowners about how to coexist with mountain lions. If they don’t want pumas on their property, McDonald recommends they install motion detector lights, put up fencing and clear brush or easy hiding spaces away. Parents should not let their children wander around and keep pets inside from dusk till dawn, when mountain lions are most active.

What does the future look like for mountain lions in the Bay Area? It depends who you ask. McDonald is more optimistic.

“We did find, in one of our studies that we published a couple of years ago, that lions can do really well at the urban edge, if they’re allowed to be here,” said McDonald. “And the reason for that is, wild pumas in wilderness areas have to work much harder for food and the subsidies that they can find at the urban edge — because being around human areas means there’s a lot more critters they can get.”

But Stoner is more doubtful.

“It’s a mixed bag,” said Stoner. We will certainly lose them from the most urban areas. But then, other places, they’ll expand into.”

Stoner’s research focuses on the long-term, large-scale distribution of mountain lions in the West. He said mountain lions have started pushing beyond what was once their normal habitat, past the Rocky Mountains and into the Great Plains. They’ve also pushed northward as climate change warms habitats, following deer up to the boreal forests and Southern Alaska.

“I suspect we will have mountain lions in the future, just not everywhere that we have them now,” said Stoner. “They’re very tenacious, very resilient.”

Sarah Bowen is a journalism major and philosophy minor originally from Los Angeles. She transferred to SF State from the University of Oregon in 2021....