How Much Screen Time is Too Much?

Tech devices are a necessity for college, but learning to log off can be difficult.

A SF State student facetimes her friend while laying on the grass of the quad after a long day of classes in San Francisco, Calif., on April 5, 2023. (Tatyana Ekmekjian / Xpress Magazine)

Angry clouds give way to sheets of rain while students take cover inside SF State’s Cesar Chavez Student Center. Inside the dining room, the squeaks from wet shoes are loud, the coffee is hot and the music is bumping from the overhead speakers. Students pass through, avoiding eye contact. Their heads are down, and as the squeaks grow louder and more frequent, no one seems to look up. There is no match for the powerhouse earbuds-smartphone combo.

All the seats are occupied in the main lobby just outside the campus bookstore. Five seats, five phones, five heads down, together in digital solidarity. Feet squeaking, umbrellas dripping, nothing breaks their gaze.

The girl with curly hair briefly takes a break from scrolling to pose for a selfie as she pulls at a lock of her hair that springs back. There’s a break in the squeaks. They start again as a student emerges from the outside only to pull his phone out of his pocket immediately, his eyes gaze down and his neck hunches over like the rest of them.

(Tatyana Ekmekjian)

A lap around the building and it’s evident there’s a problem (anecdotally) among the student body.

“Swiping on apps is inherently rewarding due to a dopamine hit in the brain every time a new message is received,” University of Southern California psychology lecturer Julie Albright explained to USC Trojan Family Magazine. “The affected area is the same ‘pleasure center’ activated by cocaine and other addictive drugs.”

In March, the San Mateo County superintendent and school board filed lawsuits against companies including Google, Snap — the parent company of Snapchat — and ByteDance — TikTok’s parent company —“claiming the companies unlawfully created ‘provocative and toxic’ content to addict and entrap young people, leaving schools to address a destructive and growing youth mental health crisis,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Most recently, the state of Utah is working to pass a law that could put significant limitations on access to social media platforms for minors. Anyone under the age of 18 would be required to get parental consent to join social media platforms, and parents would also have access to their posts and messages. A social media curfew for minors would also be set under Utah’s new law.

But where does that leave college students? With most students being in the age range of 18 to 23, some may consider themselves to be both a teenager and an “adult” at the same time.

“As you get into the 18-year-olds, they’re obviously adults,” explains Dr. Elizabeth Nadiv, M.D. and Kaiser Permanente pediatrician. “Explaining to them how it does affect their well-being, you know, to be missing out on the importance of connectivity, making sure kids are aware of how important it is to be connected with people. And to have those face-to-face interactions as opposed to having everything be on the screen.”

Matthew Rivera sits alone at a table in a trance over the game Mobile Legends. He’s more than willing to speak, but his eyes never break away from the screen.

The 19-year-old SF State freshman psychology major got his first phone at 7 years old. Though he claims he doesn’t have a problem disconnecting, his eye contact, or lack thereof suggests a different story. Although he didn’t confirm the number, he estimates he spends around eight hours daily on his phone.

At first glance, Kevya Jacob’s built-in screen time tracker tells the 22-year-old SF State student that she spends five hours and five minutes a day on average on her phone. She suspected that it was low due to midterms. When she dug a bit deeper, the phone told a different story. The week prior she spent nine hours and six minutes daily on her phone, which she confirmed was more of an accurate description. She stated that she spends most of her time on Twitter and TikTok, roughly 30 hours a week on TikTok alone if she had to guess. Though she tries to not let it distract her from her schoolwork.

“I take a break sometimes when I feel like I need to really focus on my stuff,” Jacob said. “Today I haven’t gone on TikTok yet because I have to do an essay by tonight, so I don’t want to be distracted by everything.”

SF State senior political science major Ethan Lee estimates he spends upwards of eight hours daily on his phone. He recognizes it as a problem and distraction. During finals week, he took it upon himself to download an app, something essentially similar to a parental control, to hold himself accountable.

“When I study, I tend to just check my texts and then start scrolling,” Lee said. “Sometimes I’ll be in the library for three hours and an hour will just be on Instagram.”

Perhaps the liveliest bunch that morning was the group of four SF State kinesiology majors sitting at a table together. Although four phones and two laptops shared the table with them, they all engaged in conversation and seemingly enjoyed one another’s company. When asked how much time they each spend on their phones, they all jokingly cringed before checking for the information. The average for their table was four hours and 59 minutes daily, an interesting comparison to those individuals who sat alone.

In high school, social media drove Madeline Danaher to try to be better, in “unattainable ways.” Today, a freshman at the University of Hawaii, she’s the only person she knows who has a parental lock on her phone, allowing her one hour daily for TikTok and Instagram combined.

“It’s kind of annoying, because I’m legally an adult in college and my mom still has a time limit on my phone,” Danaher said. “So that’s kind of annoying, but I guess sometimes I’m glad I don’t have the option to scroll for hours.”

Danaher notices when her friends get sucked into their phones, they have a harder time wanting to do other things. Without the parental control, she imagines she would end up spending more time on her phone as well.

“But probably not be glued to it,” Danaher adds.

An article published in the Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport, and Tourism Education in 2021 shows that students have transformed.

“Our students have changed radically,” it reads. “Today’s students are no longer the people our education system was designed to teach. Therefore, higher education institutions should be aware of the possibilities that technology brings and facilitate new learning environments.”

Regardless of the problems that may arise from the overuse of smartphones, social media and electronic devices, current university students have grown up in a digital world. Incorporating technology into so many facets of life — it’s now deemed vital.

Jenny Lederer, SF State linguistics coordinator and associate professor in English and literature, leans into the more adaptive approach when it comes to technology. Though she notices students are “totally sucked into their phones,” she mostly embraced the digital era and social media and even incorporates it into some of her teachings.

“One thing to note is that digital communication has been the norm for this generation like 18-to 22-year-olds,” Lederer explains. “And so that practice is what they’re most comfortable with and fluent in, just as far as their communication. That doesn’t mean there aren’t all the negatives associated with social media, but that’s certainly the norm for them.”

Lederer currently teaches a class on computer-mediated communication, English 122: The Evolution of Language in the Digital Age. She combats these negatives by having students analyze their own phone usage, encouraging a more conscious approach to screen time.

“So, the main idea is getting the students to find patterns in all of these different aspects of their online communication.”

When she surveys her English 122 students at the end of each semester, they always have the same response: they are more comfortable texting than they are speaking to a person, especially a person they are not very close with.

“They feel like they have more control over the message,” Lederer said. “It has something to do with this idea of control in the representation and their identity.”

Although Lederer is aware of the potential negative effects of technology and screen time, she opts to work with the technological world rather than fight against it.

“My takeaway is that it’s a paradox,” Lederer said. “Social media ironically allows constant communication with people that you’re not physically present with. And then simultaneously serves as an obstacle to building authentic, long-term relationships.”

Though Nadiv, a pediatrician for 18 years, believes problems with sleep, obesity and mental illness (mainly anxiety and depression) stem from excessive use of screen time and social media, it’s hard to determine they are the exact cause.

For now, the problem lies mostly in observation. Without a causal link, it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly the problem is.

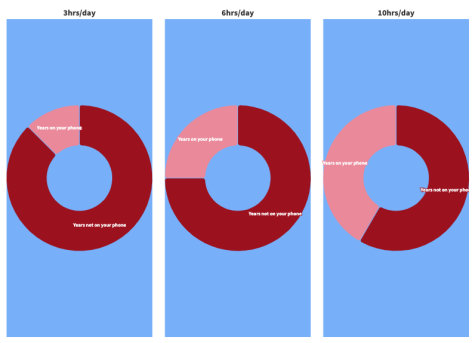

There’s no magic number for the amount of time adults should or should not spend on screens, especially given how much of today’s world is online, from homework to work, shopping, doctors’ appointments, music and even dating.

How much of your life are you spending on your phone?

However, Nadiv points to an outline from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine of six ways to optimize our health: healthy eating, physical activity, stress management, avoidance of risky substances, restorative sleep and social connection. And while there is no limit per se on how long adults should or should not spend on devices, the problem lies when it disrupts a healthy lifestyle.

“Unfortunately, I think screen time interferes with all of these,” Nadiv said. “When the screen interrupts any of this, then it becomes problematic.”

Angelina Casolla, born and raised in San Francisco, is a staff writer for Xpress Magazine. Prior to attending SF State she attended Cal State Long Beach...

Tatyana Ekmekjian (she/her) is graduating this spring with a major in photojournalism and a minor in hospitality and tourism management at SF State. Tatyana...