Love Letters from Leo

Decades after his death, Leo Stillwell’s legacy lives on through fine arts students.

The nerves along one side of the young boy’s spine were severed, leaving a 12-inch scar on the small of his back. Living in pain and needing to wear a corset to keep his spine straight, he regularly took painkillers while still managing to lift the morale of his hospital roommates.

“They tried hard to keep him — to help him stay alive. They could tell that he had so much to live for… but there was nothing anyone could do — there was not a thing, dear darling, that anyone could do to prolong his life,” explained Josephine Stillwell, the boy’s mother, 39 years after his death in 1948.

Twenty-three years old when he died, Leo Douglas Stillwell Jr. was no stranger to struggle. He was often alone. With his father away at sea in the Navy and without siblings, much of Leo’s time was spent learning how to draw and paint, resulting in his proficiency with many mediums at an incredibly young age. Despite the hardships he endured, Stillwell lived a life unimaginable to most, fostering a deep connection to the world around him through his artwork depicting scenes of San Francisco in the 1930s and ’40s.

Having a father in the military, Stillwell’s family traveled often. He spent some time in Panama when he was seven years old, but was primarily raised in San Diego, according to his mother. By his arrival in San Francisco, Stillwell had produced hundreds of sketches, oil paintings and sculptures. Before his death, the Legion of Honor and several other galleries and museums across California showcased his work. Yet, long after his death, a more intimate look into his life and artwork surfaced.

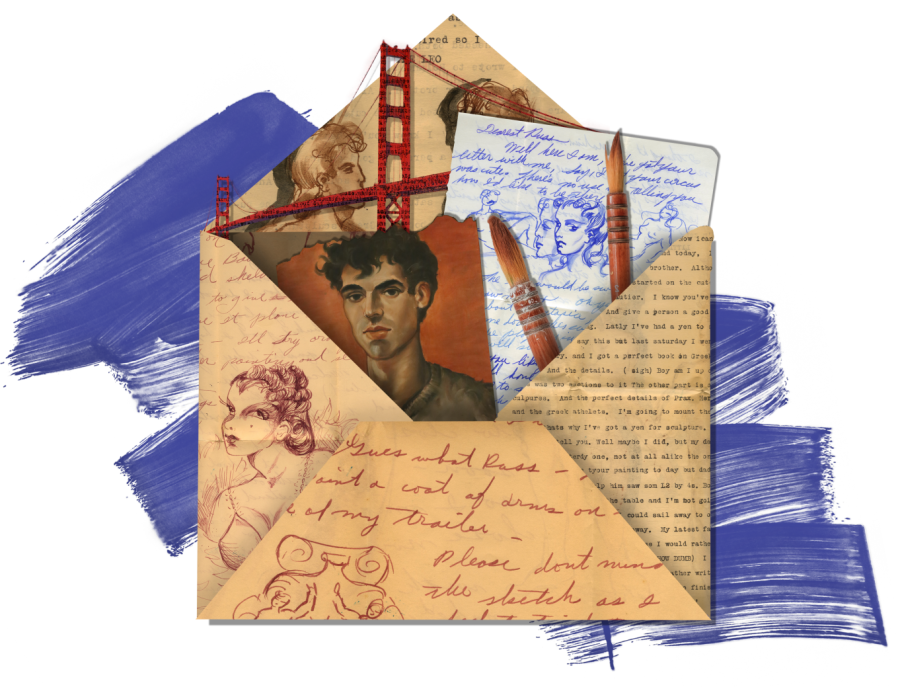

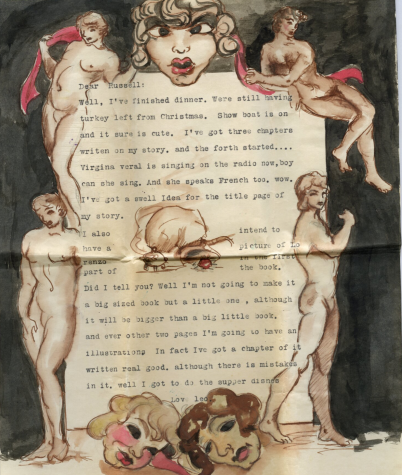

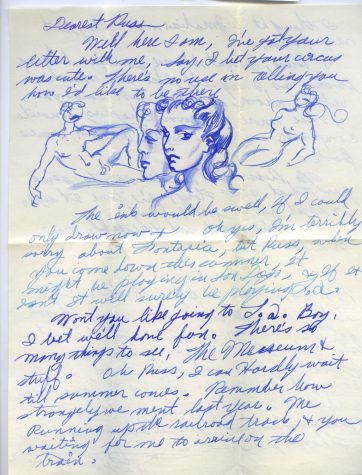

Stillwell penned close to 200 letters to Russell Hartley, a ballet dancer and costume designer who would go on to found the San Francisco Performing Arts Library, now the Museum of Performance and Design. The content of these letters varied. Some included incredibly intricate sketches and suggestions for costume designs for Hartley’s ballets; others offered simple notes of affection toward Hartley, sometimes only a few sentences long.

Through these letters, Stillwell’s life, and his sexuality, have become a fascination. In 2013, Joshua Saulpaw wrote a dissertation for a Master of Arts Art History degree at University of California Davis, titled Leo Stillwell and the Development of a Homoerotic Icon in an Emerging Queer Community. In it, Saulpaw explores the significance of Leo’s work:

“Although Stillwell lived a very short life and never received the recognition or fame that he might have with more time, Stillwell’s work is important. Not only important for the quality and potential of the art itself but because of its unique position in San Francisco at its emergence as a gay center.”

After spending several years in and out of the hospital, Stillwell succumbed to malignant hypertension, a condition caused by dangerously high blood pressure. According to his death certificate, the malignant hypertension was only the immediate cause of death. The certificate notes malignant nephrosclerosis (the hardening of artery walls) and congestive heart failure as contributors to his death. He died at the age of 22.

Stillwell used the short time he had to amass a collection of artwork that rivals that of artists who were decades his senior. Through his mother’s determination and largess, his legacy continues to fund fine arts students at SF State, a university he never attended.

In 1988, Josephine Stillwell contacted SF State about preserving her son’s artwork. The university agreed to showcase Stillwell’s work on an annual basis — what’s now known as the Stillwell Exhibit and includes a variety of his work that rotates every year. In return, Josephine Stillwell transferred ownership of the family home located at 120 Duboce Avenue, near the city’s Duboce Triangle. Within a year, the university sold the home for $250,000 and established an endowment that funds two students for up to $6,000 each year.

Sylivia Walters, acting dean of the College of Creative Arts from 1984 to 2004, is one of a few people from the university who spoke to Josephine Stillwell during the time when the future of Stillwell’s art collection remained uncertain. It’s not clear why Josephine waited until the mid-’80s to reach out to SF State, but Walters suspects that Josephine feared her son’s artwork would be lost to time as she grew older herself. Prior to Josepehine reaching out to the university, Walters recalls that, to her knowledge, Leo and his artworks were still largely unknown.

“She had suggested that the property there could be ours [SF State’s] to sell. The idea was to reassure her that we had every intention of perpetuating Leo’s memory and holding onto and preserving his work,” Walters said.

In a transcript from a meeting between Walters and Josephine on March 26, 1987, Josephine Stillwell recounts the life of her son. What was supposed to be a meeting to simply discuss the proposed agreement between the school and Josephine, turned into a long conversation in which Josephine Stillwell recounted Leo and his life in detail.

During this meeting, Leo’s mother recalled his beauty. “He had eyes with many colors in them. He had speckled eyes,” she said. When asked if her son received a lot of romantic attention, Josephine Stillwell made it clear how handsome her son was while seemingly confirming her acceptance and acknowledgment of his sexuality in the same breath: “Oh, my god are you kidding? Oh, god yes, girls and boys.”

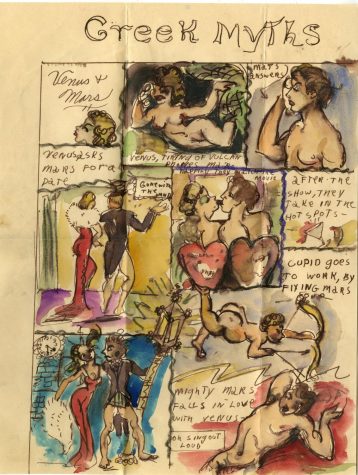

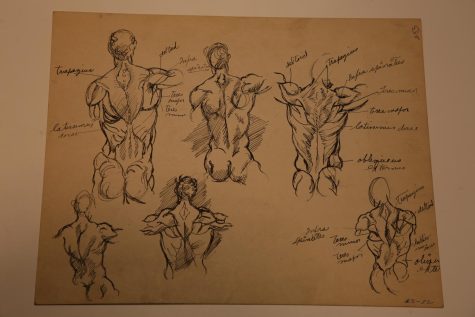

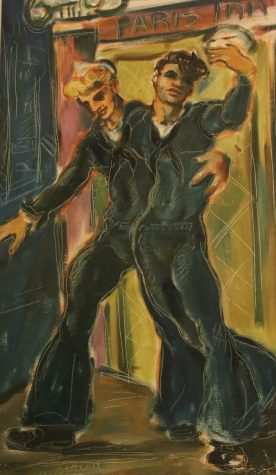

While there are no direct confirmations of Stillwell’s sexuality, it’s clear his work (no matter the medium) embraced the male form. He documented the sailors of San Francisco during World War II. His portrayal of sailors and other men in locker room scenes provides a window into the time period, and his absolute familiarity with human anatomy leaves little to be desired in terms of technical skill. Stillwell often depicted sailors homoerotically, placing special emphasis on muscular structure and detail towards the expressions of faces.

Kevin B. Chen, resident curator of the fine arts gallery on campus, firmly believes Stillwell’s talents were exceptional — especially considering his age at the time.

“I mean, if you could imagine if he lived to like 63, how much work could actually be part of the art historical canon,” Chen said. “He obviously had a talent… there was just no fear in his mark making. He could obviously render figures. This is a perfect case of somebody who was born to be an artist with a paintbrush in their hand.”

Stillwell made an effort to make sure the emotion of the scenes he created translated to viewers. He created welcoming and heartwarming scenes of affection that challenged homophobic narratives and showed Stillwell’s willingness to depict gay subculture openly.

In the book Wide Open Town, a History of Queer San Francisco to 1965, Nan Alamilla Boyd, an SF State Women and Gender Studies professor, touches on this policing of the community during World War II.

“San Francisco’s history of bar raids, shutdowns and court cases documents its transformation in the 1940s and 1950s from a wide open town where sexual subcultures flourished to a city frequently hostile to its emergent gay and lesbian communities,” Alamilla Boyd wrote.

Despite this, Stillwell appears to have been incredibly open with his sexuality based on his artwork and the letters he wrote to friends and Hartley, who is believed to have been a romantic partner of Stillwell judging by the close correspondence between the two and comments from Josephine Stillwell during her interview with Walters.

The discovery of handwritten letters found near the former residence of the Stillwell family brought new depth to the understanding we have of Leo Stillwell. According to Sharon Bliss, director of the Fine Arts Gallery at SF State, Alan Perry was the man responsible for getting the letters to SF State — he reportedly donated them after a student who was working on the annual Stillwell Exhibit reached out to him. Reportedly, he had intentions of writing a book on the artist but ultimately decided that SF State should hold onto the collection.

In an article published by the SF Chronicle, Perry was quoted explaining his reasoning for donating the collection to the fine arts gallery: “It belongs there, in San Francisco, where Leo lived. They have everything else of his.”

Theresa Von Dohlen, in 2019, was the first student tasked with the archival project of documenting, transcribing and preserving the letters. Despite the letters being in SF State’s possession for a few years, no action had been taken to document the arrival of the letters.

A second-year Museum Studies graduate student at SF State, Von Dohlen came across the letters through pure chance, as she was looking for opportunities to get more involved with art preservation at the university. For two days a week, she gathered the necessary materials and made her way through a series of locked doors within the fine arts department. In the designated scanning room, she spent roughly four hours each visit digitizing the letters.

“I would take my little box [of letters] back there,” Von Dohlen explained. “Yeah, my usual routine is that I would go get a very large coffee and a snack from Cafe 101, and I would take it all back there with me… It was a perfect project for me to really start with.”

Von Dohlen, like others, found herself falling in love with Leo’s story as she spent more and more time with the letters. According to Von Dohlen, her interest in Stillwell took on a life of its own due to how closely she worked with the letters. The COVID-19 pandemic cut her time with the documents short, forcing her to transcribe the letters from home until her graduation. Still, she remains invested in Stillwell and hopes to write a book on his life in the future.

Ivan Kudin, a 22-year-old art history graduate from SF State, described having a similar experience to Von Dohlen during his time at the university. In fall 2022, Kudin was tasked with leading the curation for the 35th annual Stillwell exhibit. He selected the artwork to be displayed and handled the installation. According to him, it was a perfect way to close out the semester.

“I just couldn’t believe the abundance of art that this person produced, especially before he died at such a young age,” Kudin said. “It was just crazy to me; it was unfathomable. And I think it’s such an honor, I mean, for the gallery, obviously, but also for me personally. It was such an honor to be able to come in contact with this archive.”

As an international student, Kudin moved from his home country of Russia to the United States when he was 17 years old. Although not explicitly the reason for his move to the U.S., Kudin commented on the current state of LGBTQ+ rights in his home country. He appreciated the sense of comfort the university and its diverse student population offered — his interactions with Stillwell’s artwork only solidified his feelings of acceptance.

“I am a gay man myself,” Kudin said, “so there’s definitely this direct connection where if I were to stay and study art in Russia, I definitely wouldn’t be able to, first and foremost, even come in contact with such a collection and an artist like that. I mean, I couldn’t say so for sure, but that’s kind of my guess. Just being able to kind of be a queer art history student myself and then being able to work on helping display and install a queer, gay man’s art was very fulfilling in that way.”

Most people familiar with Stillwell and his story would likely agree that he would be grateful, astounded and overall content with the new home his collection has found. That said, it’ll never be known for certain how he would react to the knowledge of his memory living on. What is certain, is the fact that this young man, who lived a life more interesting than words on a page can convey, encapsulates the wide range of talent, beauty and compassion San Francisco has to offer.

“He’s Leo. He’s just, he’s everything,” said Von Dohlen. “He’s melancholy and he’s joy. He’s the full range of human experience in that short 22 years.”

Eian Gil (he/him) is a journalism & political science student at SF state, currently serving as Xpress magazine’s editor-in-chief. Originally from...