Where Did All the Students Go?

Colleges across the state are seeing a drastic decline in class enrollment following reopenings from the pandemic.

Young Democratic Socialists of America member Bethany Padilla holds a sign for a student housing protest at SF State’s Malcom X Plaza. (Leilani Xicotencatl / Golden Gate Xpress)

Quieter quads, closed facilities, smaller classes with fewer sections. SF State students returning to campus after Covid have likely noticed these and other changes associated with a drop in enrollment. After multiple semesters of online classes and isolation, students hoped — even expected — the campus to be vibrant with students back among friends and peers.

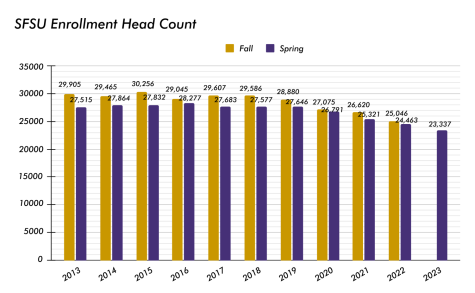

But that vibrancy has been tempered. Over the past six years, SF State’s student enrollment has declined, part of a national trend at other college campuses. SF State saw a 15% decrease in enrollment from Fall 2017–2022 and a 16% drop from Spring 2017 to Spring 2023. According to Katie Lynch, associate vice president for Enrollment Management, the trend is expected to continue until at least 2037.

Lower enrollment matters, as it means less tuition and fee revenue to support the general operating fund, which affects the student and campus experience. To worsen matters, the California State University (CSU) system — which includes SF State and 22 other campuses — will begin reallocating state support based on enrollment. Over the next three to five years, according to publicly available documents from the university, SF State will be required to resize its operations by reducing costs by $36 million. University officials expect the state allocation to decrease by 15% over three years (5% per year beginning 2024–25). So while the pandemic likely accelerated the enrollment decline, it’s not solely to blame.

“Schools across the state and country are feeling the enrollment decline,” said Lynch. “We are experiencing a decline similar to other schools that are facing the same combination of factors — shifting demographics and high cost of living.”

It’s no secret that San Francisco is home to high housing costs, and people, particularly those with kids, leave the city as a result. According to 2020 census data, San Francisco had the fewest children of any U.S. city. That contributes to fewer high school graduates in the area looking to pursue higher education.

“There are fewer students graduating high school,” said Lynch. “Similarly, the pandemic has added challenges for prospective students and families. More potential students are taking on familial responsibilities of providing care or working.”

To counteract the dwindling number of incoming freshmen, Lynch and her team plan to bridge the gap between high school graduates and new undergraduates.

“We are building stronger relationships with our local school districts and increasing opportunities to showcase SF State,” said Lynch. “We are excited about the new facilities being built on campus, such as the Science and Engineering building and a new residence hall that will make living on campus more affordable.”

SF State is a popular destination for people transferring from a community college. However, enrollment at community colleges across both the Bay Area and the country is also declining.

“We have also seen a vast decline in community college enrollment, particularly in our area, which has been where we have seen the most drastic decline in enrollment,” said Lynch. “There are simply fewer students in the transfer pool to appeal to.”

SF State has implemented efforts to counter declining enrollment among transfer students. In the past, to transfer to SF State, students needed to have completed at least 60 units at their first university. In order to attract more students though, SF State has decided to accept students who have not met that criteria.

“We have changed some policies to expand opportunities,” Lynch said. “For example, we began accepting lower-division transfer students and have seen continued growth in enrolling students who are transferring with fewer than 60 credits.”

SF State alum Jake Kronquist always knew that attending college was expected of him by his parents. Despite not knowing what he wanted to do career-wise, he attended a community college and transferred to SF State with an interest in communications and flight attending. Fast forward several years: He’s now a Delta flight attendant with a communications degree, traveling the world and getting paid to do so.

“There are countless examples of how what I learned in my major has helped me in my day-to-day life as a flight attendant,” said Kronquist. “I’m delivering urgent or difficult-to-navigate information, and having a strong background in communication gives me the confidence I need when it comes to handling these challenging situations.”

But Kronquist may be a bit of an anomaly in this regard. Graduating from college and not using a thousand-dollar degree is something not uncommon that is becoming more and more common in this day and age. According to a report done by the University of Washington, “approximately 53% of college graduates are unemployed or working in a job that doesn’t require a bachelor’s degree for about three to six months after graduation.”

The fear of job hunting and not finding work also contributes to enrollment decline — not to mention student debt being at an all-time high. Additionally, there’s the simple fact that college may not be for everyone.

Another catalyst for the decline in enrollment is the rise in popularity of trade schools.

Trade schools provide specific training for skilled crafts such as plumbing and electrician jobs. Trade school jobs can pay well, and their programs typically only require one to two years.

Bay Area native Dru Solis had always planned to play basketball and earn a degree at a four-year institution after high school. He never anticipated, however, losing his passion for the sport and gaining another for diagnostic imaging.

“When I left Oregon Tech, I knew I didn’t want to transfer to another four-year to keep playing basketball,” said Solis. “When I came back home, I started working as an electrician with my uncle for a year while waiting to get accepted into trade schools for diagnostic imaging.”

Solis now makes just shy of a six-figure salary as an MRI technologist at age 24. Despite not getting a “college experience,” Solis says trade school is something he recommends.

“Do whatever fits your wants, your needs and your lifestyle,” said Solis. “Four-year isn’t for everyone. Neither is trade school.”

Ciara O’Kelley is a current journalism major and Africana Studies minor at San Francisco State. This is their second semester working on Xpress Magazine...

Leilani Xicotencatl (she/her) is the Photo Editor for Xpress Magazine and a photographer for Golden Gate Xpress. She was born and raised in Anaheim, California....