In the heart of the Mission, the surrounding streets are spotted with canopy tents and fold-out tables belonging to street vendors. T-shirts and jeans are strung up on clotheslines for passing pedestrians to inspect, tortillas sizzle in pans of hot oil and jewelry is spread out on plaid-covered tables.

Within the outdoor community space City Station, SF State alum and Porter Vintage proprietor Katie Porter sets up tables and clothing racks packed with vintage clothes, boots, jewelry, and accessories like bandanas and sunglasses. In addition to leasing a space in City Station, Porter also has a street vendor permit for when she operates outside of the parking lot.

While Porter may be permitted, she’s one of the exceptions among other street vendors in the Mission.

“We’re here every weekend, so we gotta be as legit as possible,” Porter said.

Although their products vary immensely, there’s something many of San Francisco’s street vendors have in common: the lack of a street vending permit. San Francisco’s Public Works Department only specifies two kinds of vendors that are ineligible for a permit: vendors of alcohol and vendors of unpackaged food or drink.

Eric Molina is one such vendor. Like many other vendors, he spends his weekends at Dolores Park walking back and forth, up and down the steep hills of the park, weaving his way between picnic blankets and unleashed dogs, waiting for someone to beckon him over to make a purchase.

Molina began his career as a street vendor in the spring of 2020 after being let go from his job in the hospitality industry due to COVID-19. Originally from Peru, Molina was used to seeing people set up little shops in public spaces to sell their products. After hearing about someone making a living from selling rum and coconuts in Dolores Park, he decided to start selling mixed drinks in the park himself.

“There’s people who have to find the ways to survive,” Molina said. “The funny part for Americans is the world has changed so much, you know, what we did in South America, for survival, it became a norm.”

Indeed, this fight for survival is happening in Dolores Park. Vendors of alcoholic drinks are not uncommon in the park and neither are vendors of other prohibited substances like marijuana and psilocybin mushrooms. Although vendors like Molina do not qualify for a street vending permit, the business could still be profitable enough to withstand any potential tickets or fines.

According to Molina, Dolores Park vendors who are caught selling without a permit are told to pack up and leave. If they’re caught again, they can be fined $100-$200.

For Molina, vending can be more lucrative than most jobs. He may be making a comfortable living off his street vending, but this isn’t necessarily the case with every vendor.

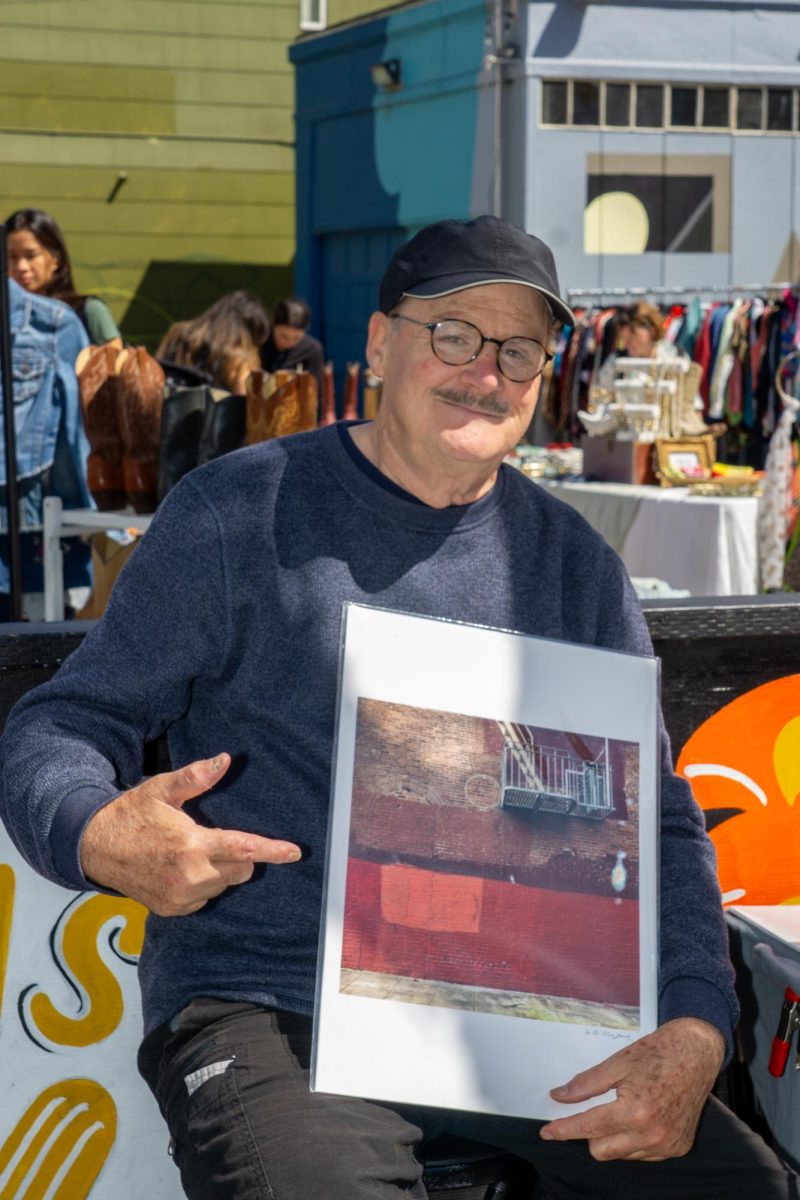

J.B. Higgins is another street vendor without a permit, but he doesn’t sell alcohol or unpackaged food. He’s a photographer who sets up his table at many of the city’s art fairs to sell prints of the scenes he captures within San Francisco.

Higgins has been taking photos since 1977 and has recently decided to make some money through his hobby. His application process came to a halt when he lost the email address he originally applied with. Qualifying for a permit might seem like a simple checklist of requirements, but unexpected issues like this can slow or even stop the process. Thankfully, Higgins’s street vending is a secondary source of income, unlike many vendors.

“This is a side hustle, but sometimes I’ll make enough money for this to be my main gig,” Higgins said.

Estella Estrella sells makeup, beauty creams and boxes of hair dye on the sidewalk of Mission Street. As a full-time vendor, Estrella is much more reliant on the profits from vending compared to Higgins. According to her, the daily profits from street vending can fluctuate dramatically.

“Sometimes it’s $100, sometimes $40 or $50, sometimes nothing,” Estrella said.

Estrella is one of these legitimate vendors who was able to obtain a street vending permit. She got her permit with the help of Calle 24, a Mission-based nonprofit that helps local Latinx business owners with the process of applying for a street vending permit. Although Estrella is now fully permitted, she still has to keep track of all business-related documents. She’s been ticketed several times after failing to show receipts of where she purchased her products.

Although Higgins and Molina haven’t been able to obtain street vending permits, the city has issued close to 200 permits since Mayor London Breed signed the street vending legislation in July 2022, according to San Francisco’s Department of Public Works Deputy Director of Policy and Communications, Beth Rubenstein.

Down the block from Estrella, Manuel Lopez sells a variety of “Mexican cravings” such as elote, chicharrones preparados and tostilocos. He also received a permit with the help of Calle 24. Like Estrella, he has sometimes been punished for failing to adhere to the rules of the street vendor permit. Even after successfully receiving permits, street vendors have to be mindful of all of the accompanying rules and regulations.

“The health department sometimes throws out our stuff… you need to have all the food covered in ice and sometimes we just forget the ice,” Lopez said.

Although the city recognizes the presence of un-permitted street vendors, there has not been any assessment of the exact number of them. According to Rubenstein, un-permitted street vendors can get wary when asked about their permit status, which makes getting an estimated number of un-permitted vendors difficult.

“We believe that there are many who are selling stolen goods and therefore would not be interested [in obtaining a permit],” Rubenstein said.

The city’s attitude is not to chastise and punish unpermitted vendors, but to educate them.

“Our inspection teams work first to educate vendors. When asked, if a vendor doesn’t have a permit, we talk to them about the process of obtaining one,” Rubenstein said.

By preventing the sale of stolen goods and enforcing health regulations on food and drink vendors, issuing permits to street vendors has made neighborhoods cleaner and safer.

“From our work with community groups, legitimate vendors have welcomed the program as it makes their neighborhoods safer and sidewalks and Muni stops more accessible,” Rubenstein said.

![[Video] No Trump, No Feds, No MAGA; San Francisco says "No Kings!"](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-28-165913-1200x675.png)

![[Video] Gators Give Heartfelt Donations to Blood Drive](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/bloodstill2-1-1200x675.png)