Since the COVID-19 pandemic, people have become much more wary of illnesses — especially during the winter. Hospitals saw the most weekly admissions for COVID-19 cases in January of 2022, with January of 2021 being the second-most, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Three years later, experts continue to warn of winter COVID surges, the Biden administration continues to offer free at-home test kits, and some people continue to wear masks in crowded places.

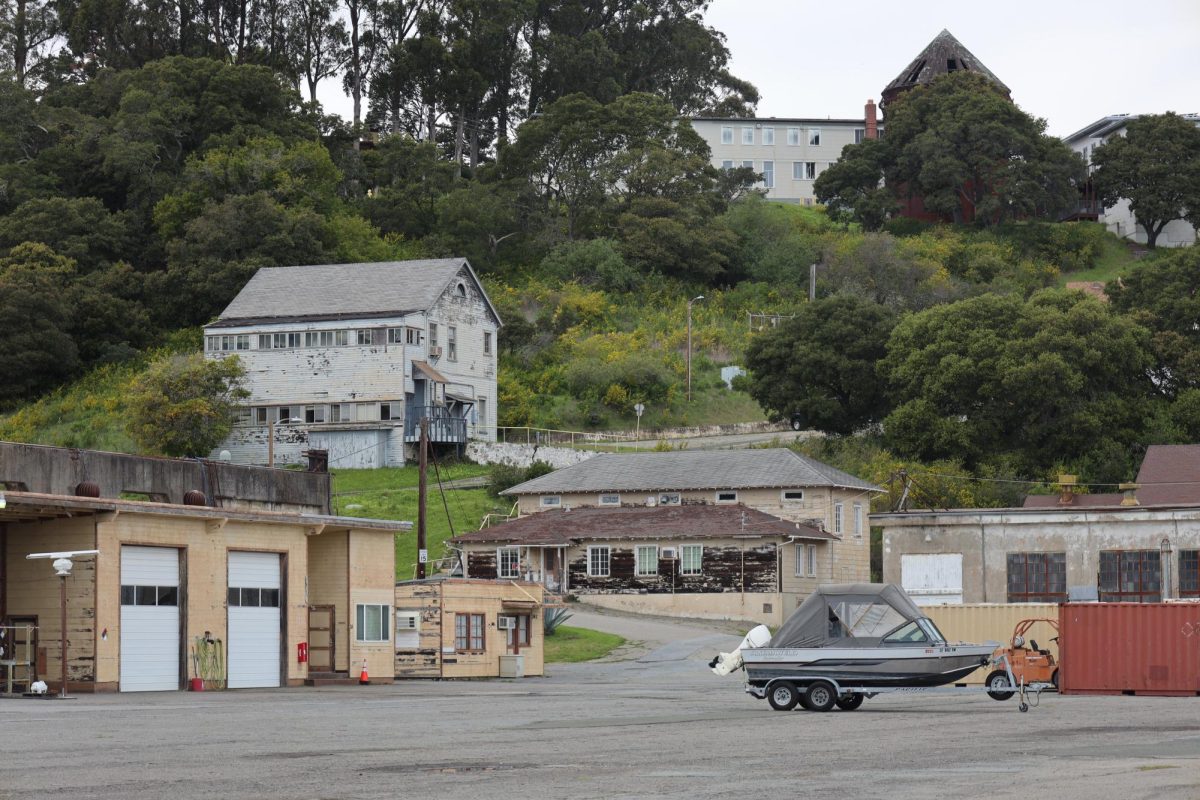

But at SF State, there is a unique method of disease detection and prevention. The SF State University Project on Environmental Pathogen Surveillance Research, or SUPER, was started by Archana Anand, an assistant professor in SF State’s biology department, and her students to track various diseases in the campus’s wastewater. SUPER is a collaborative effort between the Anand lab and Health Promotion & Wellness, the health education unit of the university’s Student Affairs & Enrollment Management office.

“This stemmed because I did this for SARS-CoV-2, which is the virus that causes COVID-19, in wastewater before I moved to SF State,” Anand said.

The experiment started in July 2023 with the replacement of four campus manhole covers. Each new cover has a hole that is about two inches in diameter in the center, through which a tampon is tied to a string and lowered into the sewer. The tampons absorb wastewater from the campus’s various buildings and residence halls. Students from the Anand lab replace the tampons every Tuesday and Thursday.

“Tampons work just as effectively as this autosampler [the device typically used for wastewater studies] because they absorb the water and would give you an estimate of what is likely to be the case between eight and 12 hours,” Anand said. “That works really well in a campus because we think if we do this twice a week, it would work just as well as a 24-hour sample.”

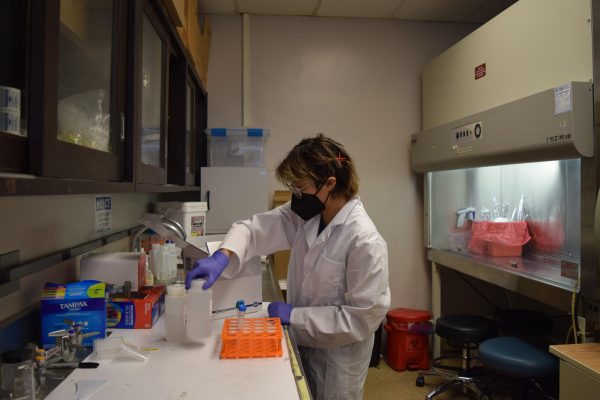

Once the wastewater is extracted from the tampons, it goes through a nanotrap. The water gets poured into an aliquot tube. Nanotrap particles are then added to the tube to capture and concentrate microbes. Magnets at the top and bottom of custom tube racks separate the microbes from any uninteresting substances such as human waste and food particles, soaps and detergents.

“This method is a very recent development,” Anand said. “It fully came out a couple of months ago. Wastewater scientists are trying to use this to process wastewater because it gives you a faster turnaround of about six to eight hours to process a sample. Before, we would take about one to two days.”

Although the wastewater used in the experiment comes strictly from the campus, the results can be applied to the rest of the Bay Area.

“With wastewater treatment plants, you can get the whole area of maybe San Francisco,” said Gabriela Franco, a fourth-year microbiology student and one of the Anand lab’s technicians. “But this is just a smaller scale of just the campus, and that can be a model for the larger scale of the Bay Area or even California.”

In the winter of 2022, the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford collaborated with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission on a similar project, which monitored the spread of COVID-19 in a nursing home in San Francisco. There is hope that the Anand lab’s project can be equally effective in aiding public health both on and off campus.

“During COVID, [wastewater research] was a powerful tool in helping hospitals and the community prepare for surges in cases before they happened,” said Karen Boyce, the director of Health Promotion & Wellness, in an email.

“Dr. Anand’s research project would allow SF State to do the same. At Health Promotion & Wellness, we use multiple data sources to plan what kinds of prevention programs and resources we offer students, such as flu shots, COVID tests and Narcan,” Boyce continued. “Having wastewater data paired with survey and trend data will increase how effective we can be. Even more exciting is that the research is being done by our own students, making it truly a student-driven response and highlights what SF State is all about.”

Edgar De Anda, a resident assistant at Village in Centennial Square, thinks SUPER can also help on-campus housing communities protect themselves from various illnesses.

“You can’t really solve a disease, but you can fix symptoms of it,” De Anda said. “That’s gonna be really helpful toward students living on campus and RAs because there’s less chance of getting a disease if you already know what the disease is, and the steps to take care of it.”

In addition to continuing SUPER into next semester, Anand hopes to eventually include more illnesses, such as sexually transmitted diseases, in the experiment’s scope, and launch a community dashboard for real-time pathogen detection.

“It’s a great tool to get a really good picture because not everyone will probably get tested on other things, but everyone uses the restroom,” Anand said. “So we’d all like to know what’s going on.”