In recent years, San Francisco has established itself as a racially diverse city. Though, for some mixed-race folks, it can still be hard to see themselves reflected in those who are in the education field, the workplace and media — the result being that some mixed-race people find it hard recognize themselves in the “race role models” that are shown in daily life and media.

But what does this do for someone’s mental health? And for someone’s identity?

This is the situation for Kiarra Enberg, a biology student at SF State who is Japanese, White and possibly Mexican. She grew up in what she considers a “generic” White American family, and the most Japanese culture she experienced was by visiting her family in Hawaii.

She tried to join a Japanese culture club in middle school but got called out on the way she looked, which was “too White.” She recalls someone within this group telling her light-heartedly that she tried too hard to be Asian.

“A lot of the people thought I was a White person who was really obsessed with Japanese culture,” Enberg said.

Cambridge Dictionary defines being bicultural as coming from two or more cultural backgrounds. Bicultural is most known to people as the term “being mixed.”

“I felt kind of hurt; one of them was one of my teachers who said that,” Enberg said. “So every time that I mentioned I was mixed-race, I felt guilty because I look very White and I do not look mixed at all. But I still feel different, and I know that I am different. I do find it interesting, but I also kind of feel like I am more of an outsider, and I worry about that.”

For Enberg, those feelings were adding up to low self-esteem and self-worth issues, and she is still dealing with it to this day. Her mom, who is half Japanese and half White, always told her to be proud of who she is. Over the years even though she is still dealing with all the feelings, she is starting to get a little bit better.

“I joined the SF State Mixed Club a month or two ago,” Enberg said. “It did kind of help me because I got to know there is so many more mixed people, since I don’t really get to meet them.”

What also helped her get through her feelings of being an imposter is talking about it with her boyfriend, who is fully Asian, as well as educating herself on her culture and learning Japanese .

Ethan Okamoto, an SF State student majoring in cinema who is mixed Japanese and White, these feelings and experiences with his heritage are quite different.

When he lived in Los Angeles, Okamoto spent most of his time in Little Tokyo, a district in Los Angeles where a lot of Japanese Americans live.

“A lot of my friends, family and community are like community activists and social community members of Little Tokyo and places like Tuesday Night Cafe,” Okamoto said Tuesday Night Cafe is an Asian American public arts and performance venue based in LA.

In 2017 he visited Japan with his family and felt really welcome over there.

“One of the cool things about going to Japan was it felt like people who I thought were the minority were the majority for the first time in my life,” Okamoto said.

Although Okamoto is half White, he did have a talk with his dad, who is of Japanese descent, about not being perceived as White or not being treated the same way as other White people because of what he looks like.

“I immediately kind of ruled out being fully White as an option. It is kind of ridiculous, I feel like that inherently erases the other side of me, because White is more like a club than a race,” Okamoto said.“White American culture is very puritan. Even though I am half-White, I am still not White, because I have that one drop of Japanese in me, which negates everything else. […] White people are not going to see you as White — that was one that stuck with me, that mentality or sentimentality, because it was immediately true as soon as I started hanging out with other kids.”

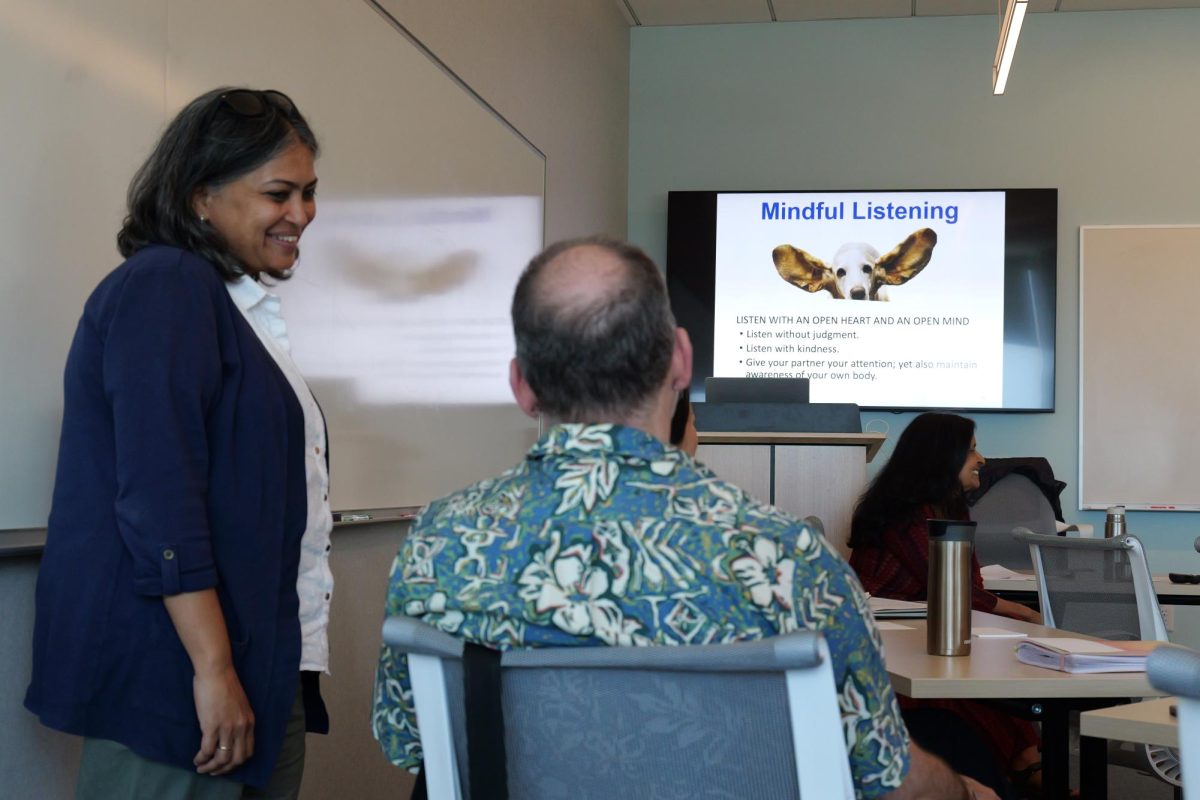

The concept of racial imposter syndrome is still unknown even in existing literature — it is mostly about imposter feelings itself, said Shuyi Liu, an assistant professor at the department of psychology at SF State. She is currently researching imposter syndrome and focusing on racial minority groups in her research.

“I absolutely think that it will be very beneficial if it is more of a known concept for everyone,” Liu said. “Because a lot of the time, those individuals feel like their experiences are not being validated because people are trying to put you in one box. We have a very binary view of individuals.”

She said that when you are not being perceived as a whole person, it affects not only how you feel, how you speak, how you behave yourself and how you present yourself in different situations. That is not going to be healthy for them overall.

“And so long-term, this will also show physically too, because there is a connection between psychological well-being and overall well-being,” Liu said.

There are several factors that cause racial imposter syndrome, Liu said. One example is the language barrier between immigrant parents and their children who have become acclimated to American life and culture. Liu says that overall, it is mostly an internal battle.

“For individuals who are more concerned about their identities, it is not just about the internal kind of anxiety they are having,” Liu said. “It is also about the messages they receive from other people: from their peers, from authority members, from even their families […]They are treating them differently or asking questions in a way that just shows their lack of knowledge in this area.”

Not knowing your heritage is something that Victoria Aloe Bell, a communications major and race and resistance minor at SF State, can relate to. She is half White and half Black, and both of her parents are also mixed. She said even though the community she was raised in was diverse, it was still very “whitewashed” to her.

“I have felt racial racial imposter syndrome many times in my life, especially in college,” Bell said. “I have had it thrown into my face.”

Once Bell got to college, that was where the identity crisis really started to settle. She became the president of Black Student Union at SF State. However, there were some issues regarding the board’s demographic, as certain people at BSU felt like the majority was light-skinned. They had an open forum that ended in an open forum which resulted in them telling Bell specifically that she was “not Black enough” and “didn’t represent the morals or the mission” of the BSU.

“They made a lot of assumptions about me based on [my skin tone],” Bell said. “I think they felt like maybe I was a little more privileged or that I must have come from wealth or high social status, which is very far from the truth.”

When she was looking for resources in high school,Bell found that there was a therapy fund that could help her: Black Girls Smile, an organization “with the mission to empower the mental health and well-being of young Black women and girls through culturally and gender-responsive educational programming, support initiatives, and resource connections.”. This fund connected her with a therapist curated to her needs — specifically someone who is mixed themself.

“I am proud to say since then I have done what I needed to do to heal from it, to really move forward, to not allow it to dictate how I view myself,” Bell said. “With a lack of the Black Student Union, I do not have black culture in my life automatically. I have to look outwards for it and that is just an emotional labor in itself.”

“All these things are things that aren’t talked about enough, but they all coexist within mixed women, whatever the mixture is, because women have that already oppressive state of being a woman, and then you feel all of the extra ways that trickles into your life based on your race, ethnicity, class — all these things,” Bell said.

Bell said for those trying to get over racial imposter syndrome, her first tip is to never stop yourself from doing something just because somebody else said it might not work.

“My second tip is join your cultural social group,” Bell said. “Even if you are an introvert, if you hate going outside, you do not want any friends or you are afraid: just go and do it,” Bell said. The best decision I ever made was going to my first BSU meeting in middle school, and though it took me a long time to really get myself grounded in the community. It changed my life for the better, and having peers who look like you is more important than most people probably realize.”

2023. (Tam Vu / Xpress Magazine) (Tam Vu)

Bell also said to go to therapy, to talk about it, to make sure you understand your feelings, because racial imposter syndrome is a very deep topic and it can have very adverse effects on your mental health.

“So as long as you’re giving yourself that open space to communicate about it and learn from others, then you’ll have the knowledge you need to equip yourself to move within the world,” Bell said.

Liu says that racial imposter syndrome might be a phenomenon that is most prominent in the United States. The word “mixed” leads people to think about a biracial individual who has one parent that is Black and one parent that isWhite. She said that speaks to how narrowly people think about race and ethnicity in general, and even culture. It is not just about the skin color or even the culture itself.

“I do think that there is a big component with racial imposter syndrome coming from the external world,” Liu added. “A lot of the time, it is because of the lack of knowledge other people have […] There’s so much effort other people can do to make those individuals have a better experience.”

Tatjana • Sep 20, 2025 at 11:28 am

This is not unique to the USA or Canada, and it doesn’t need to involve the amount of melanin in the skin. Immigrant children feel this deeply. The feeling of walking between worlds is amplified by Western culture, which profits from making people feel broken. If you don’t have a cultural identity to work from, you feel even more broken. Latin kids whose parents spoke Spanish to each other, but encouraged their children to pass. Indigenous families who left the reserve for jobs. Military children often were multiracial or multicultural. Children growing up in the foster system often feel like impostors. I was often discouraged from revealing my identity because it would make me unpopular. As a child, we already struggle with the language of identity, but to be rejected by the cultures you should be embraced by is incredibly confusing. I remember making up stories about myself so I would belong… though I never did. I think it affected my neurology and probably contributes to having depression. I feel deep compassion for my child self.