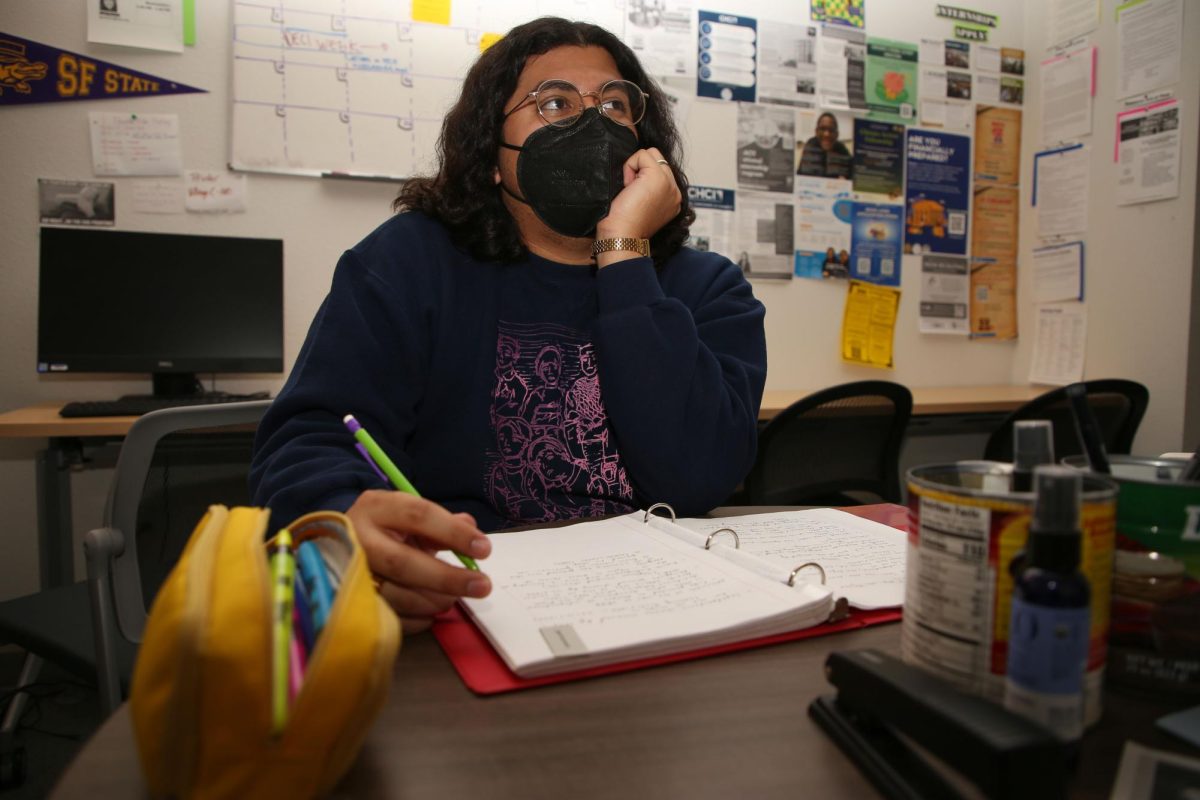

Tony Aguilar — an aspiring health care worker — thought she had finally caught her big break after she secured a four-month-long position in a clinic at the UC San Francisco Medical Center. However, once her contract ended, she faced three months of unemployment and was forced to return to working in the frontline service industry — an industry that, just months before, she felt she had finally been freed from.

Aguilar’s story of becoming stuck in entry-level fields is far from uncommon, and represents a larger trend among California’s young workers.

There are 2 million young workers in California, 61% of whom are in frontline industry jobs in settings such as restaurants and grocery stores. Many young workers face being caught in what “California’s Future is Clocked In: The Experiences of Young Workers,” a study by the UCLA Labor Center, calls a “circular labor trap.” This describes entry-level jobs that are easy to get into, but offer little to no transferable skills or upward mobility, making it difficult for trapped workers to stand out from other job applicants and move into the careers they aspire. Young workers like Aguilar are given few alternatives; they either remain in low-wage positions or face significant financial hardship with no safety nets.

Young workers also risk other factors when getting stuck in the circular labor trap. The study found that workers between the ages of 16 to 24 make up 12% of the California workforce and are a critical component of the state’s economy.

Aguilar started her academic career at SF State in Fall 2020 as a pre-nursing major, but decided to take an academic break in Fall 2022. The decision came due to a culmination of the major’s rigorous nature, an unexpected eviction and a decline in her mental health. These factors led Aguilar to focus on improving her mental health and financial situation; however, finding work proved to be a challenge.

“Since I had worked at UCSF, I told myself that I can finally leave customer service jobs — I don’t have to keep doing that no more,” said Aguilar. “I kept applying to either receptionist, front desk, entry-level medical institution jobs. That went on for two months. Absolutely nothing came out of it. So sitting on my last month of rent, I just had to pull myself up by the bootstraps and just start applying to customer service again.”

Aguilar said that she had saved money from her time at UCSF to put toward tuition once she returned to SF State. But as a result of her unemployment, she burned through $3,600 of her savings.

Many young workers balance school and work simultaneously, sometimes even being a significant financial provider to their households. According to the Labor Center’s study, young workers overwhelmingly earn low wages, work long hours and lack benefits commonly found in workplaces that are unionized. The study also found that working too many hours can hinder student-workers’ progress toward attaining a degree.

After searching for months, Aguilar finally landed a job at Safeway making $18.07 an hour — San Francisco’s minimum wage. She has been working there for the past couple of months fulfilling online orders and helping customers on the floor.

“[At Safeway] they want you to be fast, they want you to get stuff done now, at minimum wage,” said Aguilar. “It’s not great, but […] it’s stable. I would love to leave.”

Aguilar has also been trying to apply for CalFresh, an assistance program, run by the California Department of Social Services, that helps with food expenses. However, she has had difficulty with the application process because she cannot provide all of the necessary paperwork.

Despite the adversity young workers face, there are still high hopes for college graduates entering the employment world. Rebeca Gonzalez graduated from SF State with a communications degree in 2020. She was confronted with the reality of entering the workforce during a global pandemic as unemployment skyrocketed.

After graduating, Gonzalez quit her job at a phone repair store and began applying to multiple entry-level admin positions — some of which led to interviews, but never a job offer. Gonzalez felt no pressure to find work right away since she was living at home with her family, however, panic began to set in after five months went by without any leads.

“I started feeling kind of frustrated, and at one point, desperate,” said Gonzalez. “At one point I only had 12 bucks in my bank account […] and I remember that feeling, like, ‘What am I gonna do with my life?’ ”

Gonzalez was in a similar position as many of her college peers. In 2020, the SF State exit survey reported that 70% of their graduating seniors said they would be seeking employment after graduation. Of that percentage, 87% of students said that they did not have a job secured in their field of study but 50% reported being employed full-time and 46% reported being employed part-time.

After expressing her anxiety to friends and family, a friend suggested that she work as a caregiver. However, Gonzalez had envisioned entering the media field after graduating and was unsure about taking on a role so far removed from what she aspired for.

“My third day, I was like, ‘I don’t think I can [work as a caregiver]. I really cried that day,” Gonzalez said. “And I was like, ‘You know what, I need a job. I’m just going to stick with it.’ ”

Now, Gonzalez has been at her caregiver job for almost two years. She says she has fallen in love with the field and has quickly worked her way up in her company. After being at the company for a couple of months, she was offered a hybrid role where she would divide her time working as both a caregiver and an office administrator. Recently, Gonzalez received an offer for a salaried job as a community relations manager.

“This is my chance,” said Gonzalez. “I studied communications — it’s perfect. I’m very excited.”

A report by the Public Policy Institute of California shows that college degree holders have a significant advantage in the workforce over those who have a high school degree or less. California workers with a bachelor’s degree on average earn $81,000 annually but only 6% of people with less than a high school diploma earn that much. Other benefits to having a college degree are lower unemployment rates, higher quality jobs, better work benefits and more stability during economic downturns.

John Logan is a professor and department chair of the labor and employment studies department at SF State. Despite the challenges faced by workers, he is optimistic about the future of young workers’ employment opportunities, especially for those who have a college degree.

According to Logan, young workers are at the forefront of workers’ rights and have been unionizing across the nation. Even CSU students have joined the national fight for improved working environments. Graduate and undergraduate students are some of the workers unionizing and joining the fight to bring higher wages and better benefits across the board to all student workers in the CSU system. If approved, it would become one of the largest student worker unions in the United States, with over 19,300 members.

“Instead of simply quitting low-paid jobs with crappy benefits, they’ve been staying where they are, but working collectively to improve the quality of those jobs,” said Logan. “By leading those [efforts], young workers may force a change in the ‘low-road competitive strategies’ of many large American corporations.”