In theory, people go to college to build the knowledge, skills and connections that they’ll carry with them into adult life. Student publications mirror their professional counterparts in such a way that writers and editors can get a real sense of what being on staff at a newspaper or magazine is like. For most students, this is all they expect from such a program. For Jakub Mosur and Erin Lubin, it was more.

Mosur and Lubin met working on Prism, SF State’s student magazine, in 1998. The two sparked a strong connection, and eventually were married seven years to the day after they started dating. The publication not only provided them with the hands-on experience of working as both photographers and later, photo editors respectively, but also led them to their life partners. Over 20 years later, they’re still together, but the magazine that they once contributed to has come to look a lot different.

In today’s digital era, there are so many sources of information that it’s not entirely necessary to read magazines and newspapers the same way that it was decades ago. Before the industry of journalism was largely pigeonholed into publishing digitally instead of printing physical issues, college magazines used to serve their communities in ways that simply don’t exist in print anymore. Thousands of copies of each issue would be printed, as opposed to mere hundreds.

In decades past, student publications would feature local, national and international stories, and could be found all over the city in places like cafes and bookstores, instead of only in campus newsstands. Advertisements, personal inquiries, jobs and even dating opportunities were printed instead of being posted on social media as they are today.

As magazines began to digitize, many of the community-focused aspects found new homes on various websites and apps. College magazines became less practical among students and thus, less popular.

Conducting interviews with students on campus for Xpress stories will often prompt the response, “We have a school magazine?” If you’re reading this, you know that we do indeed have a student magazine; we’ve had one for over 50 years. As much effort and care as the writers and editors put into Xpress, it’s the hard truth that student publications are not as prevalent as they once were.

In 1996, when the Xpress we know today was called Prism, each new issue of the magazine would be something that students anticipated, according to former Editor-in-Chief Merrik Bush.

“Everybody knew Prism; all the students did,” said Bush. “It was during an era where people weren’t online all the time […] so they were much more aware of the different print and news apparatus that were on the campus. They would look forward to the magazine.”

THE HISTORY OF THE MAGAZINE

Prism — now Xpress — was founded in 1969, with its mission statement printed boldly on the front cover: “What this campus needs is a good, cheap, interesting magazine. Here is one for free.”

To write about the history of Prism without mentioning former advisor and instructor John Burks would be like writing politics without mentioning the president. Before Burks, staff writers were educated in the traditional, strictly objective style of newswriting; inverted pyramids and who-what-where-why’s made up the bulk of the stories published.

Burks introduced to Prism what was then known as “New Journalism”: a style of writing influenced by narrative non-fiction and popularized by publications such as Esquire and The New Yorker. Stories were allowed to be longer and more colorful, employing literary techniques and establishing characters to create the tension and drama that often makes magazine writing more captivating than cold hard news.

Velo Mitrovich, staff writer in Spring 1995 and Editor-in-Chief in Fall 1995, credits Burks with kickstarting his journalistic career.

“Without a doubt, he created me. I can’t describe what a brilliant instructor he was. I mean, he literally was my mentor,” said Mitrovich. “He spent time with me, we talked about writing, I still write today in the John Burks style of writing.”

Bestowed with Burks’ style and ambition, the Prism staff set their sights high and covered stories that extended even beyond the scope of the campus.

“Prism really was meant to engage a broader audience; because we did distribute it around the city […] it allowed us to tell bigger stories,” said Bush. “We were questioning the status quo, trying to find ways to connect our campus community to the outside world as well […] we’d stack them right next to SF Weekly and the San Francisco Bay Guardian.”

The ‘90s were also just a great time to be covering San Francisco. The electronic music scene, the LGBTQ+ scene and the rise of tech companies in the Bay Area provided Prism writers with ample opportunities to cover unique stories.

Indeed, Prism was a different animal than Xpress is today. It’s not like there is any one particular story that absolutely could not be told today, but taking a look at those older issues certainly can feel like stepping into a time machine.

PRISM IN THE 90s

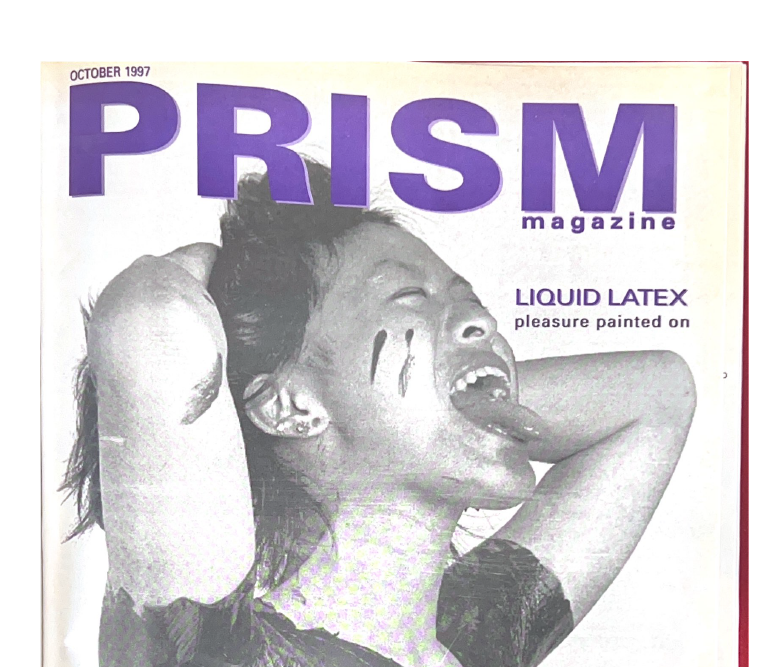

The October 1997 issue of Prism featured a rather head-turning cover; it depicted a topless woman sticking her tongue out, her chest covered only by a layer of black liquid latex. The story, titled Pour It On!, covered the kink community’s newfound interest in liquid latex as an alternative to traditional latex clothing.

San Francisco is renowned for being open and accepting of those across the spectrum of sexuality, hosting annual gay pride parades and BDSM festivals that are recognized all over the world. Public displays of sexuality have since become a bit less taboo in today’s society — even Xpress has run covers featuring nearly-nude subjects. Despite the raciness, it was a story that exemplified what was happening in San Francisco at the time.

“I would get people talking about it and I think that that one ruffled a few feathers in a way that you would expect,” said Gabriel Garner, the writer of Pour It On! “San Francisco has a thing with stuff like that so I felt like it was relevant community-wise […] we’ve got the [Folsom] Street Fair, all kinds of stuff. Where did it come from? Nobody was really talking about it yet, so I thought we’d kinda break the story.”

Articles covering sexuality were common in this era of Prism; stories about condoms, STDs and drag queens weren’t difficult to find. The exploding music scene of San Francisco in the ‘90s also provided opportunities to publish stories that explored topics such as Bay Area-based rappers and the then-burgeoning rave scene.

When readers picked up the April 1995 issue of Prism, they might have questioned what a cowboy hat-wearing-Texan holding up a Western diamondback rattlesnake has to do with SF State. The answer? Nothing.

This was exactly the point that Mitrovich, the writer of that cover story, had in mind. He felt that journalists had a duty to be worldly and not restrict their coverage to any certain geographical border. Prism was the place to show audiences outside of San Francisco what he was capable of.

Mitrovich and photographer Aaron Lauer used funds from Prism’s budget to travel to and cover the 37th Annual Sweetwater, Texas Rattlesnake Roundup: the world’s largest rattlesnake roundup event which features thousands of rattlesnakes being milked, killed and skinned. There was also a beauty pageant where the winner was rewarded with the opportunity to sing a song of their choosing from within a pit of 100 live rattlesnakes.

When Mitrovich returned to the Prism newsroom with the story, it wasn’t universally loved at first. However, when it was ultimately chosen as the cover story, it went on to win national awards. Running a Texas-based cover story in an SF State-based student publication wouldn’t make much sense if they were strictly writing for SF State students, but that wasn’t the mindset back then. The Prism staff had a broader audience in mind.

Strong emphasis was also placed on the visuals of Prism, distinguishing it from the traditional columns of the student newspaper. Before Mosur became the photo editor for Prism, he shot photos for both the magazine and the newspaper, but felt he had more creative freedom when covering a Prism story.

“We were experimenting,” said Mosur. “With Prism, all the rules went out the window; we could do anything we wanted.”

THE INTERNET ERA

The Prism staff of the late ‘90s witnessed the evolution of internet services like email and search engines, but it wasn’t yet clear that such technology would alter the world of journalism as drastically as it has. At the time, these seemed like nothing more than useful tools rather than what would become the most prevalent change within the industry.

“I thought magazines were never going to be usurped by the Digisphere […] At the time, having something published online didn’t seem credible,” said Bush. “You wanted a print byline, like, do-or-die; it had to be a print byline. The idea of doing something online felt almost like cheating, like, ‘Oh, anybody could print something online.’ ”

As the internet grew, websites and platforms emerged that gave people easier and more convenient ways to connect with each other than print media offers. Classified ads were replaced with Craigslist and other forums, while event notices began to get posted on social media instead of in print. Another staple of college magazines before the turn of the millennium — advertisers — also began moving online, eliminating a large source of income for many publications.

“It eventually, in essence, put the spiral of death on at a higher pace because a lot of these newspapers were dependent on that revenue,” said Mosur. “But unfortunately, the way that journalism is set up in the United States is that it was married to that business model.”

Eventually, in 1999, Prism was rebranded as Xpress. In its first issue, themed around the topic of “anger,” Editor-in-Chief Lateef Mungin wrote on the first page:

“You are a witness to birth and death as you read this. We are the artist formerly known as Prism magazine reincarnated as the Golden Gate Xpress. This is our premiere issue under the new name, and at the same time one of the final ones. In the near future this magazine will cease to exist. The resources used to create this publication will be used to blow up our growing website. Check out the site at www.journalism.sfsu.edu/Xpress.

The powers that be believe the internet is the future of journalism. But us page-turning dinosaurs are skeptical. We don’t want to read the writing on the wall—of computer monitors. But that’s how it is. Things change. And change makes many angry.”

Although Mungin was incorrect in saying the magazine will cease to exist, to be replaced solely by the website, he clearly saw the way that things were trending. Between then and now, the push towards online publication in favor of print has only gotten stronger.

“I could imagine that the students are distracted by so many different platforms out there,” said Mosur. “The magazines would be going up against Snapchat, Instagram and Tiktok.”

Lamenting the rise of digital news publications is like lamenting the weather. There are also advantages to having stories posted online. In our digital world, online stories can live forever and be easily read and shared by anyone in the world with an internet connection. Many journalists are adapting to this modern era and are producing podcasts and video journalism, which are now popular ways to tell stories.

Although the modern Xpress is certainly different compared to Prism, who’s to say that a future generation of journalists won’t be able to find a way to cut through all the digital noise and foster a campus community that once again anticipates the new issue — whatever medium that new issue might be in.

Melody Ip • Mar 9, 2024 at 11:16 pm

I graduated in Spring ‘99 and was on staff on the Prism during my last two semesters as a writer and a copy editor. Thanks for this recap of such a pivotal part of my journalism career!