The end of every semester presents a long to-do list for students to check off. In addition to final exams, many students are graduating. Some are moving out of dorms, and some are packing for vacation. In the midst of these responsibilities and tasks, there’s another item that never fails to pop up in their inboxes at the end of every semester: Student Evaluations of Teaching Effectiveness (SETEs). These surveys may seem rudimentary in comparison to the many other major tasks to complete, but they carry significant weight in determining the future of faculty.

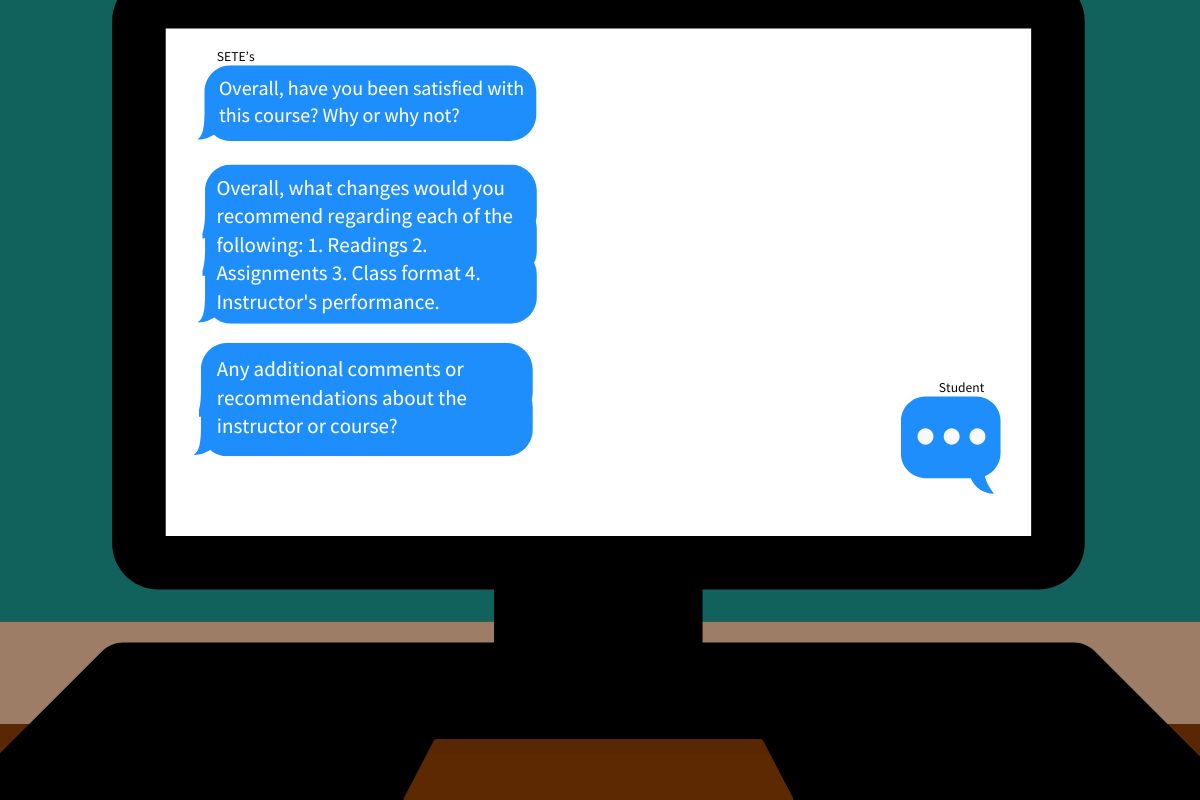

The purpose of SETEs is to improve teaching effectiveness, but faculty say they have evolved into a biased system that demoralizes them to a number, inaccurately ranks them and jeopardizes their employment opportunities. When students submit their evaluations at the end of every semester, rating their professors on a scale from 1-5, an average score is generated and the faculty member receives a number that ranks them amongst their colleagues.

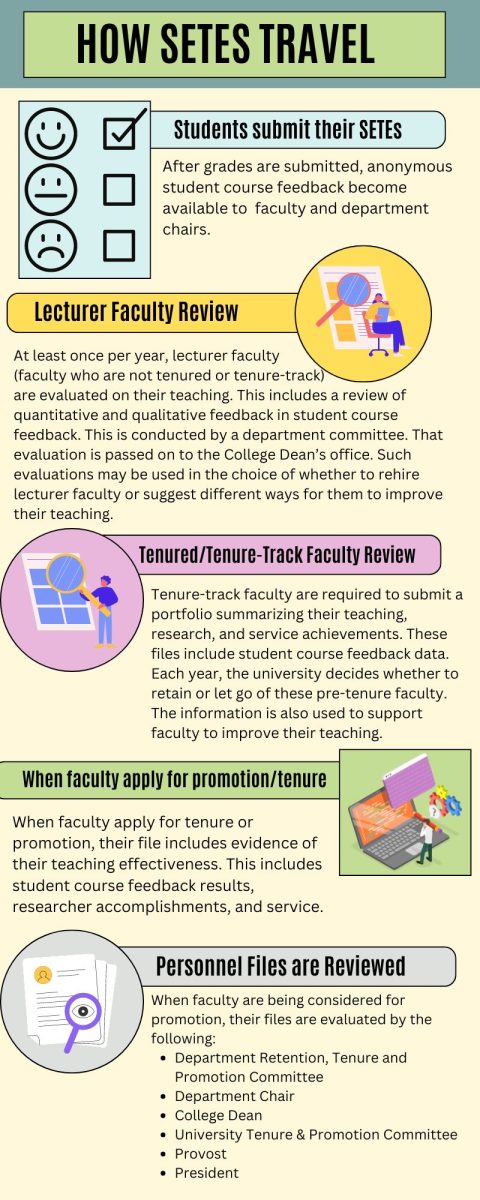

This number and their SETEs are stored in their personnel files, which are utilized to determine employment opportunities such as tenure retention and promotion.

The California Faculty Association’s San Francisco State University Chapter, the union that represents faculty, has introduced a resolution to eliminate quantitative ranking of faculty. The resolution cites several articles of evidence indicating that SETEs result in biased rankings based on gender, race and ethnicity.

Evidence from UC Berkeley statistics Professor Philip B. Stark and former Center for Teaching and Learning Director Richard Freishtat, who published a study on SETEs, exposed the rating system as built on a multitude of statistical errors. Because of the flaws and biased outcomes of these SETEs, the resolution states they violate constitutional rights. Quantitative ratings in SETEs constitute an “arbitrary classification,” which violates the Equal Protection Clause, a part of the 14th Amendment that guarantees equal treatment.

“If bias is so inherent to these, the fact that they’re used to justify employment decisions like whether to retain, to promote or even terminate someone, it seems like de facto, just on its face, a violation of labor law, which is supposed to be fair,” said Dr. Brad Erickson, CFA Chapter President for San Francisco.

Dr. Katharine Gelber, Associate Dean at the University of Queensland, Australia, is cited in the resolution for her published study on gender bias. She analyzed the written comments in teacher evaluations in all courses offered in the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland from 2015 to 2018.

Gelber’s research concluded that it is not the SETEs that lead to an amplified bias, it is the gendered norms in society that contribute to bias in evaluations of female-identified teachers in SETEs. She further explained her research in an email:

“The study I undertook with colleagues found that while there are often no numerical differences in the teaching evaluation scores received by male identified and by female identified academic teaching staff,” Gelber said, “the expectations on staff for what they need to do to be ‘good’ teachers are heavily gendered.”

Based on her studies, Gelber found that students expected female teachers to be nurturing, give extra time outside of class and do more activities for their students that are time consuming. Males, on the other hand, were rewarded by their students for subject expertise and characteristics such as being humorous.

Dr. Candace Low, SFSU lecturer in the Biology Department, said dealing with racism and misogyny in higher education is nothing new.

She started her career in higher education teaching a small summer course, for which she received positive evaluations. As she began advancing her career, she took on more intense, upper-division courses. The more advanced the courses she taught, the higher the level of disrespect she received from students.

“Given the backdrop with courses that are challenging, I have to work really hard and invest a lot to make sure that students learn something without being overwhelmed,” said Low. “It’s a challenging course, what ends up happening is that the students blame me.”

Low’s experiences of being marginalized and belittled by students is not a short list. Slammed doors, eye rolls and shouting have all been projected at her from students. At one point, she said an incident in her classroom almost became violent.

“It’s just like another layer of the kinds of reviews or the biases against women and the biases against people of color in general for not being the ‘type,’” Low said.

“I shouldn’t, at the end of every semester, not want to read them or when I see that they’re in my inbox or they’re available, my heart shouldn’t start racing and I shouldn’t go into a panic and have a stomachache and headache because they’re personal attacks.” Low said.

The qualitative comment section of the SETEs have been especially brutal for Low, who described them as belittling and bullying. Some past examples, she said, included messages such as “You suck sister!” “Get a new job,” and “You’re terrible!” in all capital letters.

Low said she’s seen the differences in how her white male counterparts are viewed.

“I haven’t read the reviews of, say, white male professors, but I’ve seen a lot more forgiveness,” said Dr. Low

Professor Daisy Zamora, lecturer in the Department of Latina/Latino Studies, also agreed with the opinion of the CFA’s resolution, not only because SETEs have various biases, she said, but because the negative reviews carry more weight than the positive reviews.

“It is a very hostile system towards teachers, which makes them hostages of the students, and especially of those who do not want to do the work required by the course and manipulate these evaluations using them as blackmail to the teacher who demands the fulfillment of their duties,” Zamora said in an email. “Those students act as customers whose demands must be accepted by the teacher, no matter how poor their performance in the course has been. Otherwise, they will give the teacher the worst possible evaluation.”

In addition to the evidence of biased results found in Stark and Freishtat’s study, the resolution also heavily criticizes the statistical science behind SETEs.

The resolution cites Stark and Freishtat’s published research, stating comparing instructors’ average scores to departmental averages statistically makes no sense. According to Stark and Freishtat’s study, there should not be a presumption that the difference between one set of numbers means the same thing as the difference between a separate set of numbers. Statistically this is nonsensical, the resolution states, because the numbers are labels, not values.

On the scale in the SETE’s quantitative section, 1 is the best score and 5 is the poorest. Low, who holds statistics as one of her main areas of expertise, said she’s heard from students who praised her and told her they ranked her 5, believing that was the best score. (9) Additionally, she said it’s very difficult for a faculty member to have an overall rank of 1.

“No one can have an average of one overall, unless you get 100% ones, because, to get a mean of something, you have to be higher and lower than whatever’s in the middle,” Low said. “ If one is the far left, like the lowest number in the whole range, you kind of have to score perfect all the time, because as soon as you get a two, which isn’t bad, your mean has gone down from one. And then if you have one person that complains, then the whole thing starts to drag toward the middle,”

Erickson said labeling a faculty to a number makes it easier and faster to make employment decisions. According to Erickson, if an administrator, such as a dean, has hundreds of employees to sign off promotions for, having a numerical rank makes that process much more convenient.

Not all faculty may feel as negatively affected by these SETEs as others. Lecturer Jacob Dinardi in the Kinesiology Department said he didn’t have any comment on whether the current SETE questions elicit biased responses, though he could be convinced.

While he acknowledged he may not be the best person to speak to on this topic, as he is a heteronormative white male, he offered his perspective of SETEs and his teaching philosophy.

“I make a real effort to connect with students… I tend to receive very good SETE evaluations in the few courses that I teach… from students of all backgrounds,” Dinardi said in an email.

According to Dinardi, the impression he is left with from the resolution is that the authors made a bad faith assertion that SETE scores are a significant factor in teaching assignments and promotion.

“I’m aware that I receive higher marks than certain colleagues of mine,” Dinardi said. “I don’t discount the idea that bias could be at play; however, at the end of the day, the SETE scores I receive do practically nothing to help me. In fact, I would argue the current CSU policies skew more toward ensuring faculty who receive lower scores are not let go than they do to ensure faculty who receive higher scores are promoted.”

Dinardi said his good SETE scores do not help him gain any additional courses to teach, nor do they play a significant role in salary increases.

Lecturer faculty typically do not teach full-time, nor are they tenured. When faculty reach tenure or tenured-track, they are subject to evaluation by more departments and committees, according to Wilson. They are also subject to more benefits, such as job security and pay increase opportunities.

“I will have to work for the CSU for practically 10 years as a part-time lecturer before I am even eligible for a pay increase,” Dinardi said. “I find that to be a much bigger issue than anything related to SETE scores. At the same time, my colleague who received not-so-great SETE scores was not shown the door, and instead was offered some peer mentoring, which I think is fair and in the interests of students.”

Academic Senate Chair-Elect Dr. Jackson Wilson explained that while SETEs are taken into account during performance reviews, there are other factors as well. He quoted the current Retention, Tenure, and Promotion Policy in an email interview.

“Effectiveness in instructing students may be demonstrated by evidence such as student evaluations, comments, and letters; and peer review and observations of teaching,” Wilson said via email.

How student feedback is used in the retention, tenure, and policy process varies by department, according to Wilson. He declined to comment on the accusations of bias and faulty statistical science surrounding SETEs.

“However, I can say that I have yet to see robust validation evidence supporting the claim that the current SETE instruments consistently measure teaching effectiveness,” Wilson said in the interview. “I believe there are better ways to collect and utilize student feedback to support excellence in teaching and learning.”

Bobby King, SFSU Director of Communications for the Office of the President, said any alterations to student evaluations would have to be negotiated between the Union and the CSU centrally. He said the current Collective Bargaining Agreement (contract) specifies that student evaluations must include a “quantitative” component.

“I was told that the Faculty Senate previously put together committees which included faculty and administrators,” said King in an email. “They spent two years looking at changes to the instrument, but the work was inconclusive.”

King said there is recognition that the evaluation instrument is imperfect, but it doesn’t seem to be detrimental to faculty’s success in being awarded tenure and promotion.

“In the past five years, the campus has awarded every applicant tenure, and only one applicant for promotion to full professor was denied,” King said.

He said the one person denied promotion to full professor has subsequently been awarded, and they were not originally denied because of student evaluative scores.

If a faculty has a supportive chair, Erickson said, they will be supported. But that is also subjective to every individual. He said if a faculty member who seems like “trouble” to the university, for example, filed a grievance against administration, the university can utilize these SETEs as excuses to not have the lecturer return for another semester.

“The numbers, which, as I mentioned, are unscientific and biased, but also the comments. The comments become a problem when they’re cherry-picked,” Erickson said. “So if the administrator finds a couple of students who said something bad about this instructor and uses that as the basis for disciplinary action, that’s also a problem.”

While SETEs may sway in a positive or negative fashion, there is no guarantee that they will be completed by students, which also affects the accuracy.

“Any survey to be scientifically valid must have a 70 % return rate,” Erickson said. “And that’s almost never the case for SETEs, so in a way, almost all the SETEs in any faculty member’s file should be destroyed. They’re just not scientifically valid.”

Maurice Vallecillo, an undergraduate senior studying International Relations, said he does submit his SETEs every semester, but only for the lecturers he has positive reviews for.

“Before [this was] explained… I was under the impression that it was to keep these classes, because we’ve been cutting a lot of classes at State, so that’s why I thought it was really important. I mean, it still is important, because it’s their job,” Vallecillo said.

He said now that he understands SETEs and the resolution to abolish them, he wouldn’t participate anymore.

Erickson and Low agreed that student evaluations are essential for effective teaching. Erickson also suggested sending evaluations out in the middle of the semester, when there is still time to implement their students’ feedback.

Erickson said the resolution has passed the Faculty Union. The next step would be to bring it to the statewide union for a vote in the assembly.

“If it passes the statewide Assembly of Union members, then the next step would be to propose something different in the contract.”

Casual Observer • Apr 29, 2025 at 7:53 am

This would be an interesting time to follow up on this article. Most lecturer faculty at SFSU have had their courses cut by 40-60% and many are being laid off at the end of Spring 2025. The message from Department Chairs and the Deans has been “performance is not a factor.” This would means both SETE scores and departmental performance reviews were not used in determining which professors would be subject to course cuts and/or let go.

It directly contradicts the information in this article. It’s also worth asking if cutting courses across the board and keeping lectures, some of whom seem to be experiencing burnout based on their SETEs, simply because they’ve been around the longest makes sense. Does that benefit students? Does that benefit the institution – especially in a time when strategies to boost enrollment are needed more than ever? And, lastly, has the University been transparent with students that they don’t really take their evaluations of the faculty seriously? These seem like fair and relevant questions to ask.