This story has been updated. A previous version of this story can be found here.

We’ve all heard some version of the phrase: we learn in different ways. American cartoonist George Evans’ famous quote, “Every student can learn, just not on the same day or in the same way,” is still printed and posted as a motivational phrase today. While this subjectivity may seem like a socially acceptable notion, it does not jive well with the politics of higher education.

Student evaluations in higher education were developed nearly 100 years ago by psychologists Herman H. Remmers and Edwin R. Guthrie, according to the article, Student Evaluations of Teaching Encourages Poor Teaching and Contributes to Grade Inflation: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis by Wolfgang Stroebe. The psychologists wanted to provide teachers with information about student perception, but warned that “it would be a serious misuse of this information to accept it as an ultimate measure of merit,” according to Stroebe’s article.

What are ‘SETEs’?

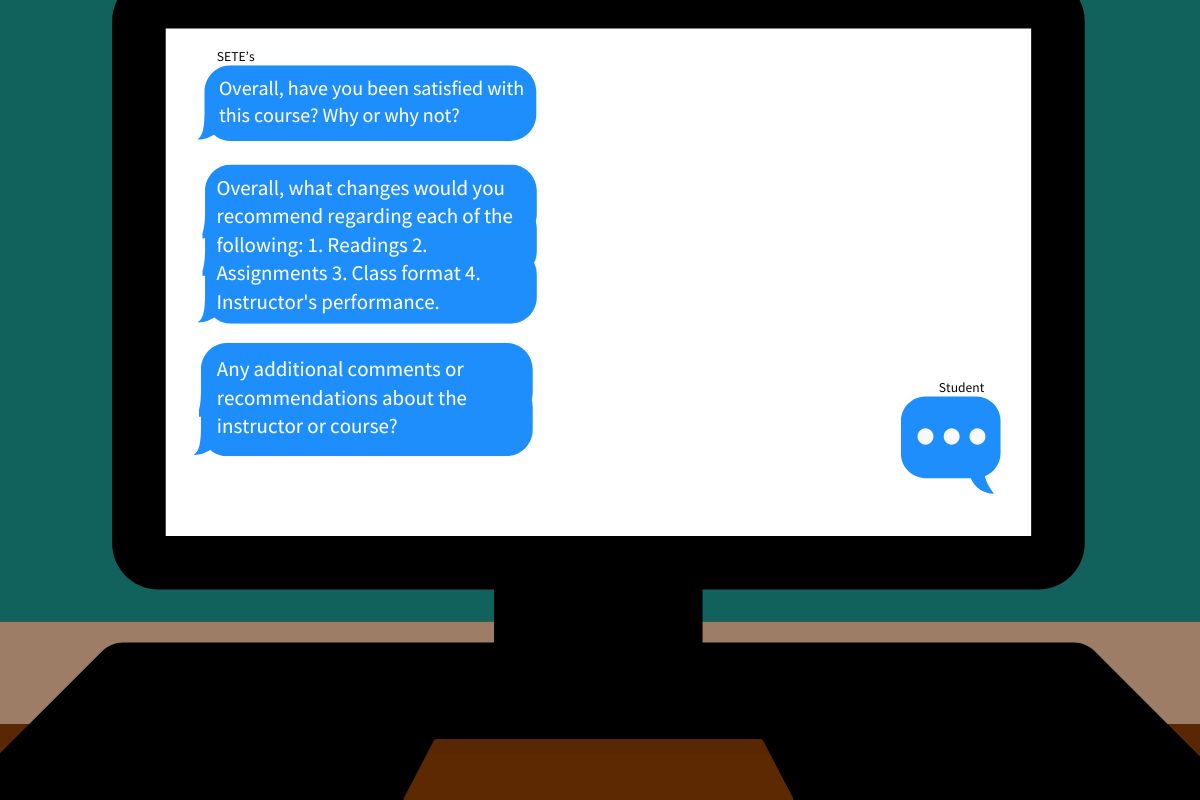

College students around the nation, in the midst of final exams and summer plans, are receiving notifications from their universities to complete their Student Evaluations of Teaching Effectiveness. These anonymous surveys, commonly referred to as SETEs or SETs, act as a feedback tool for students to rate the effectiveness of their teachers.

These surveys are commonly put into faculty personnel files and used for retention, tenure and promotion decisions. Earlier this year, San Francisco State University Faculty Association passed a resolution to abolish the current SETE criteria. It is one of many universities joining the movement to reform student evaluations.

Gabriela Weaver, professor of chemistry at University of Massachusetts Amherst and assistant dean for student success analytics, began teaching when she was 27-years-old. As a petite woman, she said that she noticed right away certain types of comments that she found surprising, such as remarks about her clothing and a sense that students felt like she should be “mothering” them instead of teaching them.

Weaver has been teaching for nearly 30 years now. Yet, it wasn’t until about 12 years ago, when she was on the Faculty Senate at Purdue University, that she became a part of the discussion around reforming student evaluations. A faculty senate committee was formed, Weaver said, to discuss the pros and cons of student evaluations and what could be done differently.

“At that time, we were focused mostly on maybe the questions should be worded differently, or maybe the forms should be handed out in a different way during a different time in the semester,” Weaver said. “Those kinds of things, really kind of superficial changes to some extent.”

Weaver moved away and left Purdue before the committee could do much, and subsequently became the Director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at the University of Massachusetts. In this role, she became the institutional representative for Bayview Alliance, also known as BVA, a network of research universities.

At her first BVA meeting, she proposed a project that institutional partners could be interested in.

“I proposed two different things,” Weaver said. “And the one about teaching evaluation piqued the interest of several people there.”

That was the beginning of the partnership between the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Kansas, Weaver said. Their research around student evaluations, titled the TEval Project (Transforming the Evaluation of Teaching), was funded by the National Science Foundation in 2017. The University of Michigan was also brought on as a partner when they applied for their National Science Foundation grant.

According to an article published by Weaver and her team, their research is “a multi-institution collaboration to refine and implement a teaching evaluation framework that addresses the shortcomings of typical approaches. “

Evaluation system promotes biased results and is built on flawed statistics

The reform movement widely recognizes two egregious issues: the biased results promoted by student evaluations and their scientific and statistical inaccuracy. Multiple literature is cited in the discussion around reform that indicate gender and race bias in student evaluations, including studies that indicate people of color and people with accents tend to receive lower evaluation scores compared to white individuals.

In addition to the problem of bias, Weaver said, the other problem has to do with the fact that there is no data that connects the teaching evaluation scores to how students actually learn. Measuring student learning, she said, requires carefully designed metrics.

“And if student learning is what we care about when we’re saying that we measure teaching, then, these measures – the student evaluations – aren’t correlated in any way to that,” Weaver stated.

“And yet, if you look at how these evaluation measures are used at the time of promotion or annual merit, they are very high stakes,” Weaver said. “So sometimes they are the only measure that’s used to determine if somebody will keep their job, get promoted, get a raise.”

Phoebe Young, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), said she noticed pretty early on that there was something problematic about student evaluations, called Faculty Course Questionnaires (FCQ), at CU Boulder.

Young said several of the female faculties she knows receive comments on their evaluations at the end of the semester, including herself.

“It says, ‘smile more’. So that sort of suggests that there’s something weird going on with how students are being asked to evaluate their own experience, right?” Young said. “So, it didn’t make me think that they were worthless, but it made me think, ‘Okay, you sort of have to take them with a grain of salt.’”

Experiences like these, Young said, make early career faculty feel not only skeptical, but also anxious because it affects their career.

University response

Since CU Boulder’s involvement in the TEval movement, many things have changed. For one, the kinds of questions put into student evaluations have transformed.

When Young began teaching at the university in 2009, student evaluation questions included very broad questions, such as ‘rate the instructoroverall,’ ‘rate the course overall,’ ‘rate how much you learned in this course,’ ‘rate the intellectual challenge of this course’ and a prompt question that required the student to form an opinion for the class as a whole: ‘rate this instructor’s respect for and professional treatment of all students regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion, sexual orientation or veteran status.’

Today, evaluation questions at CU Boulder aim at gauging the personal learning experience of students rather than speaking for the class as a whole or the instructor’s intentions. The first half of questions begin with the phrase ‘In this course, I was encouraged to…’ and offer scenarios such as ‘interact with others in a respectful way’, ‘reflect on what I was learning’, ‘connect my learning to ‘real world’ issues or life experiences’ and ‘contribute my ideas and thoughts’.

In addition to the reforming of questions, criteria has been established on how departments handle inappropriate qualitative comments in evaluations at CU Boulder. According to their FCQ Terms of Service, prohibited behaviors include attacks on a protected class, use of slurs or derogatory terms, threats or intimidation and impersonation. Consequences for submitting such comments include having that FCQ removed, referring the student to the Office of Institutional Equity and Compliance and disciplinary action.

Additionally, the University of Southern California not only changed how evaluations are used against faculty, it removed them from the tenure review process.

Morgan Polikoff, professor of education at USC, is on the Rossier Committee that changed the way his department uses these surveys. Similar to CU Boulder’s reform, he said the department has weeded out questions that contain language asking the student to rate the course or professor “overall.”

“I think there’s the thought that that’s sort of less prone to bias,” Polikoff said. “That’s a university-wide thing.”

The university has also changed the way the data of these surveys are used, specifically in employment decisions.

“So, the instructional ratings that students give, the quantitative metrics, those are not reported in tenure and promotion cases, even for teaching faculty,” Polikoff explained. “For full-time teaching faculty, the numbers are not ever used.”

“Now that said, when we’re evaluating people, we have the evaluations in front of us, and we can go and look at them,” Polikoff said. “And it’s possible that the numbers might influence the way that people think about whether someone’s a good teacher or a bad teacher or something like that. But we do not use the numbers in any formal reporting, and, I would say we’re discouraged from relying on the numbers.”

Faculty jobs at stake

The accuracy of the quantitative data that result from student surveys has been a point of criticism in the movement to reform evaluations. Philip B. Stark, a UC Berkeley statistics professor, has published research on the statistical flaws behind student evaluation systems.

“I started to look at student evaluations seriously as a researcher,” Stark said. “It was sort of obvious from the beginning that they don’t measure what they claim to measure. And that’s reflected in student comments as much as anything else, that they comment on things that have nothing to do with the quality of instruction, or learning or anything else.”

Stark said he received comments in his evaluations during the early years of his teaching that included comments such as ‘looks good in a black turtleneck’ and ‘lose the shoes’.

When he became chair of his department over 10 years ago, he became responsible for promotion cases. It especially bothered him, he said, that the university was relying on a system that did not have a lot of empirical support.

Stark published his research with Richard Freishtat, former Center for Teaching and Learning Director. Their research garnered attention, and Stark has since been invited to give advice to a number of universities around the U.S. and Canada, including written expert reports and testifying at arbitrations.

“One of the statistical fallacies that many studies, many observational studies of student evaluations commit is to say, ‘Oh, we looked at the average scores of female instructors and male instructors, and they’re not very different. Therefore, there’s no gender bias’,” Stark said.

But that, he said, is asking the wrong question.

“What you need to know is, if you compare equally effective instructors or instructors who are doing the same thing, do they get the same rating regardless of gender?” Stark stated.

What a woman needs to do to get her ratings up, Stark said, is much more difficult and expensive of her time than what a man needs to do to get his ratings up.

There is evidence, Stark said, to support that several factors outside of the instructor’s control can influence evaluation scores, such as race, age, accents and the condition of the classroom. His research suggests not only is this system skewed to implicit bias, it is also overall scientifically flawed.

One of the major problems Stark described is administering student surveys through a Likert scale, which measures a person’s opinion, usually how strongly they agree or disagree with something. At SF State, the Likert scale ranges from 1 to 5, with one being the best and five being the worst.

The problem is, Stark said, that an individual may make inconsistent ratings of something depending on their mood, for example, what they ate for breakfast, or whether they got a good grade on the last test. A ‘five’ for one individual may not mean the same ‘five’ for another individual.

“It’s just very difficult to justify combining a bunch of different people’s subjective fives together,” Stark said. “Then, when you start talking about doing something like taking an average, taking an average is implicitly saying that the difference between a one and a two means the same thing as the difference between a four and a five. And, if you are only summarizing things by averages, you’re basically saying there’s no difference between getting a one and a five and getting two threes.”

He added in an email that teaching about controversial subjects can really tank somebody’s evaluations as well.

“There’s a tendency to conflate how somebody feels about highly charged material (e.g., the situation in Gaza, laws around reproductive rights, affirmative action) with how they feel about the instructor,” Stark said. “I’ve seen this take a big toll on some instructors’ scores.”

Another widely agreed upon issue among scholars is the lack of response rate in student evaluations. According to Young, even in some classes, trying to get above a 50% response rate can be difficult. Many of the methods applied to try to improve this, Stark said, have perverse consequences. For example, giving students extra credit or releasing grades early encourages ‘throwaway responses’.

Stark’s research has been cited in many arguments to reform student evaluations, including SF State’s Faculty Association’s resolution to remove SETEs from faculty personnel files.

Candace Low, lecturer in SF State’s biology department, stated in an email that SETEs pose no obvious benefits, and they do more harm than good.

“I say this because they help to perpetuate biases, and this will never be an advantage for underrepresented groups in academia,” Low said.

“If you don’t ‘fit the part’,” Low said, people will judge you more harshly.”

“Then, if [you] add on top of this lack of accountability and a culture or habit of unfiltered opinions on social media, this is a recipe for bullying and defamation,” Low stated in an email.

Low said student evaluations can ruin a person’s career. She referenced Maitland Jones Jr., an NYU professor who lost his job after students petitioned against him.

“Chairs can be forgiving or punitive, depending on their own prejudices, projections and preconditions,” Low stated.

Wei Ming Dariotis, professor emerita of Asian American studies at SF State, helped author the Faculty Association’s resolution. One of her major reform ideas for student evaluations, she said, came to her one night as an epiphany: nowhere in teaching effectiveness assessment could she find the mission of the institution aligned with the assessment.

“So, I had this epiphany that we should be asking, how does this course contribute to the mission of the institution and SF State’s mission statement?” Dariotis said, pointing out that SF State’s mission statement aligns with social justice.

Dariotis led the creation and implementation of the JEDIPI Institute: Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Pedagogies in Inclusive Excellence in online teaching.

“And I had people coming to me left and right,” Dariotis said. “I had 400 faculty out of the 1800 at SF State completely through this 25-hour intensive training in anti-racist pedagogy and inclusive pedagogy. I had a whole team of people that I worked with, and I had a team of three other women that created it.”

It occurred to her, Dariotis said, that the existing student evaluation system does not allow for, and, in fact, punishes faculty pedagogical innovation. In other words, Dariotis said, faculty are expected to already know how to teach. And then they’re not given any room to learn new things.

This led to Dariotis creating a task force on teaching effectiveness assessment.

Removing the harmful bias from the data, Dariotis said, cannot be done, both quantitatively or qualitatively. For example, even if a committee member sees a student’s qualitative comment as clearly biased or racist, the quantitative score that the student gave the faculty is still considered.

Dariotis agreed with Weaver’s findings in that studies show there is zero correlation between getting good SETE scores and affecting positive impacts on student success.

Dariotis and her task force worked on reforming the evaluation questions into two parts: a formative questionnaire at the beginning of the semester and a summative questionnaire at the end. Questions at the beginning included: ‘What are you, your classmates, and your instructor doing that’s supporting or enhancing your learning and success in this class?’ And, ‘What do you, your classmates, and/or your instructor need to change in order to improve your learning and success in this class?’

“That gives you actionable data,” Dariotis said. “It tells you what’s working and what needs to change. Not just what the student would like to change, what needs to change. It also asks the students to take a lot of responsibility for the learning environment.”

The summative questions at the end would state the university’s mission statement and ask the student to describe the ways the course helped contribute to that mission. Part of what is needed, Dariotis explained, is transparency for the student to understand the weight of their questions.

In addition to surveying the ways in which the course contributed to the university’s mission statement, Dariotis and her team added another question, which she said administrators should actually be making extraordinary employment decisions upon.

‘Did you feel safe and respected emotionally, physically, and intellectually in this course?’

To address the transparency issue, Dariotis said, a series of possible responses are given:

Yes

Yes, and I want to nominate my instructor for a teaching award.

No

No, and I want the instructor to know I said ‘no.’

No, and I want the instructor to have their instructor’s supervisor talk to them about it.

No, and the instructor needs to get support around these specific aspects of their teaching (with a list of possible things that they could be focused on).

No, and I would like to enter into a restorative justice mediation process.

No, and I would like somebody to talk to me about filing a grievance.

“There should be clarity,” Dariotis stated.

Today, Dariotis is a professor emerita, no longer at SF State, and the road to reforming how student evaluations are used is a long one. She and her team applied for a grant with the Spencer Family Foundation to do a larger-scale study, which they were not able to secure. The resolution she helped draft has passed the faculty union and will go to the statewide union for a vote in the assembly.

The idea of changing the evaluation of teaching came not only from wanting to address some of the weaknesses of this existing system, Weaver said, but also to create a system that would lead to the use of teaching methods that are correlated with student improvement, with improved learning, with improved outcomes. Weaver said this means moving away from something that has no correlation to methods that could, in fact, support student success.

“So, I think that there’s definitely an appetite nationally for a movement on changing the way teaching evaluation is done, not just changing how you ask the questions on the student surveys, but actually looking at the entire approach to it,” Weaver stated.

According to a June 2023 press release from TEval, “Participants from more than 25 U.S. and Canadian institutions have agreed to combine their efforts to transform the way teaching is evaluated at colleges and universities.”

There is widespread agreement among scholars, namely those mentioned in this article, that student feedback should not be abolished. However, there is also widespread agreement that the current system is flawed at best. There are high stakes in a survey that is meant to be taken by students who vary in emotions and understanding of the questions at hand.

“How do we expect students to take them seriously and put the time in to give thoughtful responses when they have no idea how they are used and what the purpose is?” Dariotis said. “And how do we expect administrators, department chairs, tenure and promotion committees to make useful interpretations of student evaluations when they’re not given any [statistical] training?”

People, especially non-tenured faculty, Stark said, lose their jobs over this.

![[Video] Gators Give Heartfelt Donations to Blood Drive](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/bloodstill2-1-1200x675.png)