Deep breath in … hold … exhale … repeat. As children, our first exposure to wellness-based practices is commonly taught through deep-breathing exercises. We often take this practice with us into our adult lives as a way to self-regulate psychological and emotional sensations.

More than half of Gen Zers report feeling overwhelmed by local, nationwide and global events, according to a UNICEF Youth Mental Health report. Data from the 2024-2025 Healthy Minds Survey further revealed that only one-third of college students describe having ‘positive mental health.’

Economics professor Anoshua Chaudhuri, who is also the senior director of the Center for Equity and Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CEETL) at SF State, says that there is an increase in mental-health-related disruptions in the classroom, “Faculty don’t feel they have the wherewithal to be the mental health first aiders.”

What would happen if professors implemented deep breathing and other wellness techniques in college classes?

Wellness? What’s that?

Self-regulation falls under the domain of wellness — which can be vaguely defined as “feeling and functioning well” in physical, social, cognitive and mental contexts, Research Scientist Kiat Hui Khng explains in a study. Mindfulness, the awareness that materializes when intentionally paying attention, is often attached at the hip with wellness.

Jeff Duncan-Andrade, a professor of Latino/Latina studies at SF State, works with teachers in K-12 education globally to make wellness a priority in schools.

“Unfortunately, there’s very few schools and school districts that genuinely prioritize wellness,” Duncan-Andrade said. “As a result, a lot of young people, and a lot of adults that work in schools, are not well.” He believes implementing wellness in the classroom begins with the community collectively defining what wellness means.

Mindful Pedagogy

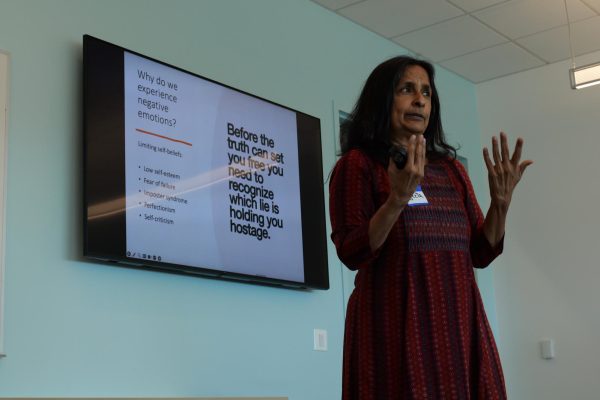

Jennifer Daubenmier, the Interim Faculty Director at CEETL and co-director of holistic health studies, believes wellness is a “multi-component construct” that encompasses all aspects of the classroom: physical, psychological and social.

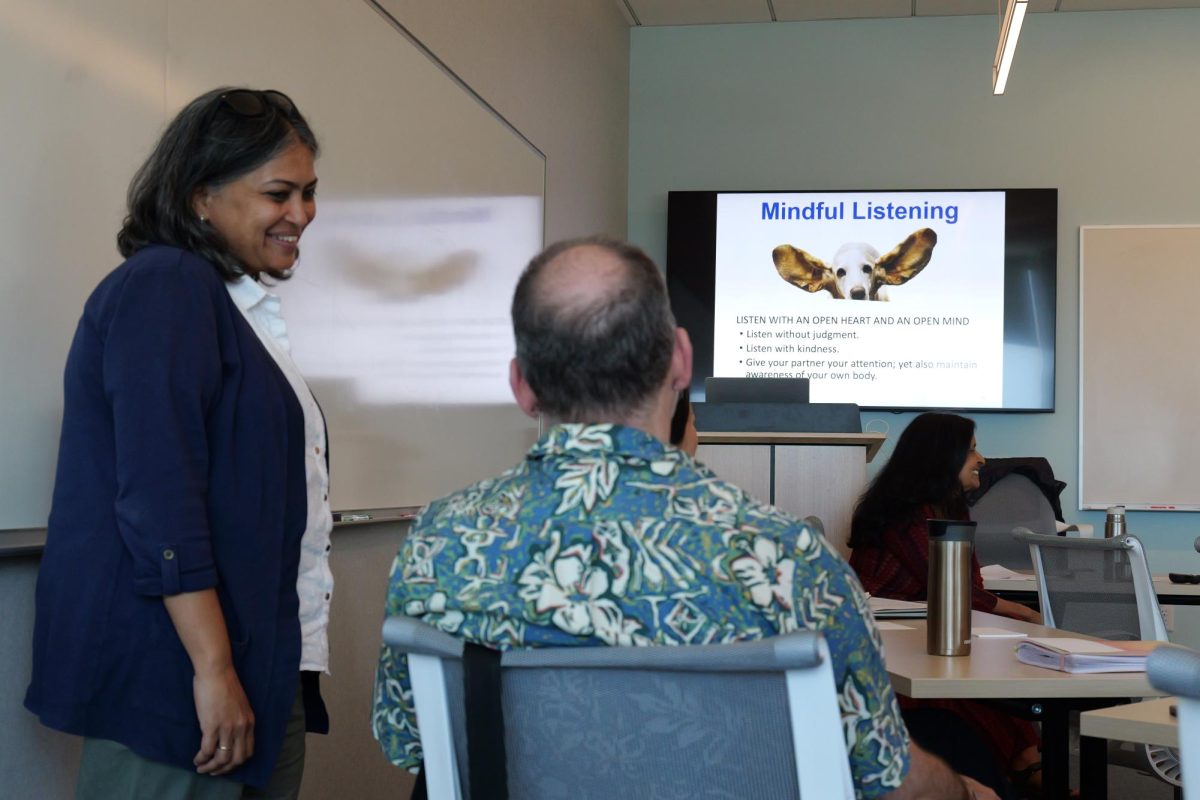

Daubenmier and Ranjeeta Basu from CSU San Marcos led CEETL’s Introduction to Mindful Pedagogy event, held on Sept. 26 at the Science & Engineering Innovation Center. The event centered around practices professors could implement into their classes to reduce stress, anxiety and procrastination in students.

The event brought faculty together and taught them calming practices that can be implemented in their lives and in the classroom to enhance the learning environment. For example, a short meditation at the start of a class can help a student transition from one task to the next, helping them feel more present.

A mindfulness-based activity that raised giggles among attendees of the event was a guided meditation with cell phones. Daubenmier asked attendees to place their phones by their side and explore the thoughts and emotions that arise when looking and holding the cell phone. Attendees were then asked to share their experience with those around them.

Daubenmier explained how teaching faculty these practices can reflect onto their students: “The students will kind of pick up on it, and it can kind of shape the classroom dynamics and the culture a little bit.”

Disruptions in the classroom

Daubenmier shares that the attitudes an educator displays can affect a students’ reception to disruptive situations, such as when a student may be having a mental-health-related episode.

“[The professor] was basically just queuing to everyone that, yeah, you guys know what’s already happening,” notes second-year student Powelle Funa, who witnessed a fellow classmate have a panic attack during a quiz.

The teacher maintained a calm environment, signalling that the situation was under control, which made Funa feel at ease. The professor was aware of the student’s panic attack, which allowed for the maintenance of the classroom environment while the student self-regulated.

What does classroom wellness look like?

CEETL’s Project Coordinator Jesus Alvarez III expresses that, for faculty, practicing wellness may mean having an opportunity to step outside of their everyday routine. He says it’s difficult to go home and marinate in the stress of an exhausting day of work. CEETL-sponsored activities, like “We Wednesdays,” bring faculty with shared interests together as an alternative respite; the last event was hosted in SF State’s Fine Arts Gallery.

“I feel like those kinds of breaks in between are something to kind of just spread all that stress out so you’re feeling better,” Alvarez said.

Genievive Del Mundo-Mendieta, a former faculty member and CEETL’s teaching and learning specialist, understands the importance of providing a space for wellness practices within classes; as such, she allows outdoor breaks on the grass near the Humanities Building.

“I just was thinking, okay, I want to give my students tools on what wellness means to me,” Mendieta said.

Mendieta also had a colleague who is a healer come into the classroom to lead a meditation.

“Not all students are into it, I mean I wasn’t into it when I was a college student,” Mendieta said. But she highlights the importance of giving students the opportunity to try out mindfulness techniques, exposing them to these kinds of wellness practices and providing them with the tools for it.

Coming together

As Mendieta highlighted, not every student may be receptive to mindfulness and wellness practices in the classroom. Many students feel that it’s too cringey to participate in these exercises. However, she emphasizes that prioritizing faculty and equipping them with the tools to become more present in the classroom has positive effects for all, and can help provide students with resources they otherwise may not feel comfortable asking for.

“We have some resources on campus, but not enough,” Daubenmier said. “Addressing mental health in the classroom as we can as faculty is another resource, and I think that can also benefit the faculty’s mental health.”

Duncan-Andrade is a testament to this: while teaching a high school literature class, he received a phone call about his father’s passing. After returning from the call, Duncan-Andrade paused the lesson and the class sat in a discussion circle.

“Some of the best medicine that I got to move through that woundedness, it came from my students,” he said. “My students knew that this had happened before my own wife knew, because that’s where I got the call.”

Duncan-Andrade says, “We can create educational environments like that, but that requires both a will and a skill.”