“Do you know what normal boobs look like?” my mom asked, facing me in her closet as I sifted through her clothes.

The question didn’t faze me. In our “no questions off limits” household, nothing really did. I never thought twice about her scarred chest — it was all I knew.

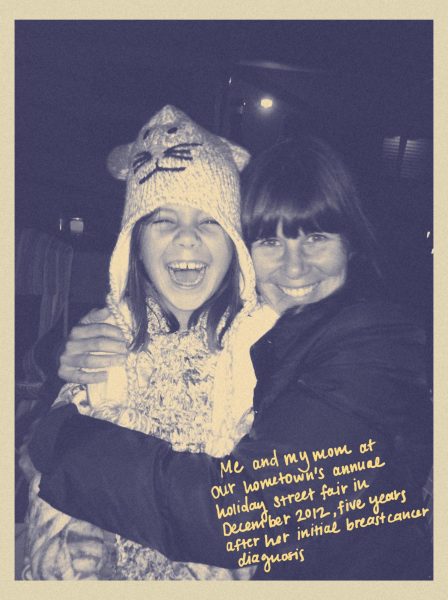

When I was three, doctors diagnosed my mom with stage-two breast cancer, and later that year, at 35, she underwent a double mastectomy and multiple rounds of chemotherapy. I don’t remember much of it, except the sound of the electric razor my brother used to shave off her long brown hair in our home at the end of GardenDale Road.

At the time, I was 10, and she wanted to make sure that I understood that my set — that inevitable marker of womanhood headed my way — wouldn’t look like hers. That was the first time I understood that breast cancer was more than a disease — it was a fault line that would shape my life, and the lives of so many others.

Two years later, my parents sat my brother and me down in our living room as the evening’s darkness crept in. It was the same year that would’ve marked my mom’s eighth “cancerversary” — another year of being cancer free. Except she wasn’t. Her dormant cancer cells had metastasized to her skull as stage-four cancer.

The word cancer had made me skeptical. Would she still be here to zip up my wedding dress or meet my future children? Somehow, though, my parents counteracted my fears. They painted a different ending, one in which mom would be there. They explained the treatment plan that would manage, if not cure, my mom’s cancer.

Her treatment was backed by scientific research and progress — people with breast cancer were being diagnosed and living longer, thanks to more widespread mammography, targeted therapies and genetic testing. I grew up under the impression that by the time I reached the age when breast cancer could take my life, there would be treatments to combat the thing that, in the end, would take her life. Now, I’m not so sure.

For the past several months, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — the primary benefactor of cancer research since 1937 and biomedical research’s leading public funder — has grabbed headlines. In response to executive orders issued during the Trump administration regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, the NIH has had to watch the pendulum swing in terms of cancer research and funding priorities. We know these cuts are already disrupting the development and progress of research projects. For instance, around 2,300 NIH grants, totaling close to $3.8 billion in funding, were cut this past June. But this discontinuance in funding also carries the consequence — one that reaches far beyond the laboratories and grant reports: the breast cancer patient only an arm’s reach away from many of us.

In 2016, the Cancer Moonshot — funded by the 21st Century Cures Act — launched, intending to accelerate a decade’s worth of progress in cancer prevention into five years. Reestablished in 2022, the moonshot made significant progress in bringing cancer one step closer to an end by connecting patients, researchers and clinicians to leverage government, private sector and academic resources. The White House — through changing administrations — has paid attention to cancer, though at times more than others. Today, the fate of cancer research remains uncertain.

Dr. Christoper Koenig, a former oncology researcher at UCSF and an SF State communications studies professor, pointed out that defunding NIH grants poses a heavy impact on the basic and social science investigation of significant health issues. In an email, he explained that research that may have strong empirical evidence but includes keywords that are now deemed to be “woke” — equity, racism, women’s reproductive health — are now being silenced.

“At a moment in time where we should be more hopeful and confident than ever,” said Dr. Marcie Mennes, a breast cancer survivor and physician specializing in child psychology, “we have to grapple with the unnecessary intentional halting of life-saving research. … This doesn’t have to happen. … They are deliberately withholding funds for life-saving research.”

Optimism was an unusual side effect of my mom’s cancer. It was partly defined by the momentum she saw in cancer research.

Her cancer had a tendency to outlive the different prognoses given to her. This wasn’t luck: it was her participation in clinical trials stemming from the research that her oncologist — on the cutting edge of metastatic breast cancer research at University of California, San Diego — was doing. But my mom’s life being prolonged past her prognosis because of extensive research isn’t a unique narrative.

One in eight women in the U.S. will be diagnosed with breast cancer. Since the peak of its mortality rate in 1989, breast cancer death rates have decreased 44% in 2022 (with the notable exception of American Indian and Alaska Native women). This is a result of decades of research, subsequent advances in treatment and earlier detection that had been made possible for people.

“You’ll get your first mammogram earlier than the rest of your friends,” my mom told me, adding, “they won’t find anything — but just in case.” Although no direct evidence points to this as an effective strategy, women with a first-degree family connection to breast cancer are encouraged to get their first mammography 10 years prior to the age when their family member was diagnosed.

But, as Koenig points out, the Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has “‘shifted priorities’ in women’s health, [and] clinicians no longer have access to basic guidelines for breast cancer screening and reproductive health from the US FDA to help women make decisions about the health care they need.”

Hearing that I would get screened early made my childish imagination think my genetic lottery made me a part of an exclusive club — a club that meant tagging along with my mom each week to pick up her drugs from the CVS pharmacist who knew her by first name, making animals out of the blue latex gloves in hospital rooms, badgering her into buying a lavender wig so I could wear it too (she never wore it and neither did I). Eventually, it meant taking her oncologist’s advice and trying hormone-free birth control which didn’t heighten my risk of breast cancer. I am my mom’s daughter, after all.

My mom’s grandmother died of breast cancer, and my mom used her death as a time stamp to illustrate how much cancer research has evolved since she died in the early ’70s. She was confident that, had today’s treatment been around back then, her grandma would have survived. When conversations with my mom turned to preventative measures for me, she’d reassure my fears, reminding me that research evolves and will continue to do so.

Maya Draisin was rediagnosed with breast cancer in June and her grandmother also had breast cancer. Draisin underwent a staggered chemotherapy trial at UCSF as an alternative to more aggressive options. To her, the difference in cancer treatment today is a result of the leaps and bounds research has made.

When Paul Webb, a senior science officer and program manager at California Institute of Regenerative Medicine, entered his career in cancer research — which eventually landed him at UCSF — had yet to know his work would intertwine intimately with his life. His first wife was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004 and died after it returned seven years later. He shared that, more recently, his second wife was diagnosed with almost a carbon copy of his first wife’s diagnosis.

In 1983, Webb began researching estrogen for his PhD. Around the same time, a treatment for HER2-positive — a subtype of breast cancer that was untreatable without chemotherapy and surgery — was still being researched. By 1998, Herceptin — a therapy developed by Roche, formerly Genentech, to target it — was already approved by the FDA.

One of those lives that Herceptin saved is Mennes. Soon after finding out she was pregnant with her second child, Mennes was diagnosed with HER2+ breast cancer.

“Luckily, I did rely on the science,” she said. “I was diagnosed in 2005, but had I been diagnosed in, like, 1995 or 1985, it would have had a much higher mortality rate.”

At 43, Amy Hash was diagnosed with triple positive — estrogen positive, progesterone positive, and HER2+ — stage-two-and-a-half breast cancer. She underwent 31 rounds of chemotherapy and, similar to Mennes, was treated with Herceptin.

“If you had gotten HER2+ 20 years ago, it was an immediate death sentence, right. But they have new drugs,” said Hash.

Hash is a part of a breast cancer support group with Ashley Goldsmith, a cancer patient in remission — coincidentally, both are SF State alums and former Xpress staffers. Hash and Goldsmith separately observed how their treatments differed from others with similar diagnoses, even five years prior.

“The drugs that they’re going to get now are not the same drugs that I got six years ago because modern medicine has advanced that much,” explained Hash.

When I began reporting on this story, I remembered an audio recording of a conversation between my brother and my mom. When I listened to it again recently, all I could hear was how significant of a role research played in her quality and length of life. “I don’t think I would still be here,” she told my brother. She was nodding to her gratitude toward her oncologist that got her into the clinical trials that prolonged her life several years.

Webb explains that when research projects are in their first stages, government funding, both federal and state, is the propagator in moving them forward. Then as the research advances into the later stages of clinical trials, private companies typically become the main funder for continuing their trials while they wait for FDA approval. According to Webb, patients currently being treated with available drugs have a good chance of continued access as long as the healthcare system is receiving funds.

“What stops is new ideas that are required to bring in new treatments that will help people,” said Webb.

So if the beginning stages of academic research are no longer funded federally, then the later stages may never happen. State funding certainly can’t cover all stages of research.

Some of that research — and the potential for treatments and drugs — close to reaching answers could now be prevented from finding them. Triple negative breast cancer — a subtype of breast cancer that lacks a targeted therapy — is immersed in research. Yet, under the current circumstances and funding cuts, this research is at risk of being affected, explained Webb.

“We’re all hopeful for all of these drugs that are currently in trials to move forward because it means that it extends not just our life, but it means the people who come after us maybe [they] don’t have to do such extreme treatments or don’t have to worry about recurrence,” said Hash.

While Hash’s treatments were successful and her chances of cancer returning are low, there is still a chance. “I’m looking at some of these trials to be really, really giving me a guarantee,” she said.

She keeps a close eye on the CLEVER trial — which, if approved, could come close to guaranteeing that any dormant cancer cells wouldn’t reoccur or metastasize — and the PROMISE study — which is testing a drug that would allow women who went through chemical menopause to receive estrogen’s benefits with a drug called Duavee. Even though both of these trials are reaching their later stages, she worries that funding cuts could end them.

“I am really watching. Really, really, really watching and praying and just sitting here holding my breath for these to … go into phase three and pass.”

Webb doesn’t expect the effects of federal cuts to affect patients this year. “Where you’ll see the difference is how it looks in terms of continuous improvement in 10 years time, or 20 years time, and that’s where the impact will be,” said Webb. “It’s going to be a slow, slow starvation.”

Research gives us scientific advancements and life-saving treatments, but it also gives us tangible hope — hope that families like mine could hold on to that evening in our living room.

“I think the chilling effect is that the hope pauses,” said Hash. “We had things that were getting close to really being life altering for people. Not only to extend their life and let them live so they can continue to raise their children or meet their grandchildren, but it means that their day-in-and-day-out existence could be so much better.”

Yet, here we are: At a momentous time, maybe the height of cancer research, it’s halting. And while research can pause, cancer won’t.

Niels Mohler • Oct 24, 2025 at 6:58 am

Your piece is powerful and heartfelt — it beautifully honors your mother’s strength while reminding us why cancer research matters so deeply. NM

Alice Keeton • Oct 23, 2025 at 7:07 pm

Bailey,

What an insightful narrative embracing both the emotional and the scientific aspects and explaining the political implications of the present reality.

You have had an in depth education and a good understanding and this certainly qualifies you to stand up and speak up.

Well done!

ZM • Oct 23, 2025 at 6:49 pm

Incredible Bailey. Keep spreading truth and awareness. Your mom is so proud of you ♥️