By Julian Lim

Photos by Lorisa Salvatin

Only half of the emerald neon sign is on. A grouping of the center letters, which in whole spell out “Mission Cultural Center,” is nearly invisible in the sunset-darkened Mission District of San Francisco.

The lobby beneath the sign is empty. A soft rhythmic thud pulsates through the ceiling. There is no one around except for a woman selling one-day class tickets behind the Plexiglas window.

“The screen printing class is on the fourth floor,” she says. “Take the elevator up.”

The elevator only goes up to three. As the arm-length industrial lift reaches its final ascent, the small room fills with muted noise heard below, only for it to be revealed as the doors slide open. The air is thick with the slams of foot stomps, trumpet riffs, and a heavy bassline that pounds through your chest.

To get to the other side, where the stairs to the fourth and final floor are located, you must navigate pass the Tuesday night Flamenco and advanced Mexican Folk Dance classes, the open door hovering parents, and through the narrow incandescently lit hallways.

At the top of the steps and to the right of a six-feet-tall screen-printed anatomical skull is the Mission Grafica—the thirty-seven-year-old graphics studio with a long-standing history of making

political posters for the Mission.

Up here—in the attic space of a building, which used to be Shaff’s Furniture Company,—the red wooden floorboards covered with ink splotches are bouncing to the thumping soul of the center.

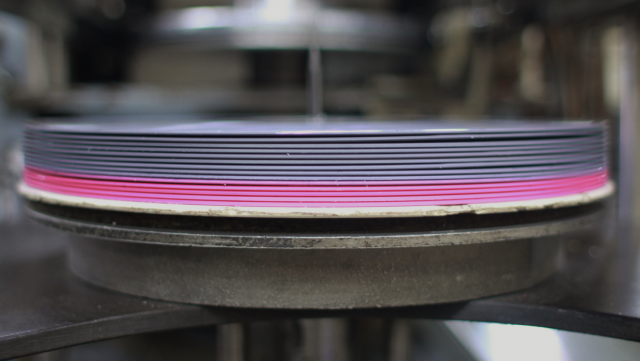

The Grafica’s print shop holds five black-painted workstations adorned with hinge clamps, which are used to hold down the silkscreen frames with the burned design. Around the shop, three metal drying stations with forty to fifty racks are leafed together like pages in a book; they are filled with layers of flatstock poster prints, and fabrics from past workshops and classes.

In the corner between two of the drying stations, an out of commission screen-printing machine sits with used transparencies piled underneath the ripped yellow silk screen. There is a six-by-six-foot backlit power washing station and a dark room around the corner where the photo emulsion is applied for image burning.

In nearly every facet of the shop, hundreds of ink-stained silkscreens in aluminum and wooden frames are stacked on the floor, shelves, and dolly carts tagged with marked masking tape.

“The ethos of printmaking is supposed to be about access,” says Amy Diaz-Infante, one of Mission Grafica’s screen printing instructors. “That is why I love a shop like the Grafica.”

Diaz-Infante has only been teaching at the Mission Grafica since July, but has been involved with the shop for years. When she received her master’s in fine arts, she learned how to screen print at the Grafica.

“You can come in without knowing anything or you can be a veteran printmaker and it does not matter,” she says. “We are all here printing in the same space and learning from each other.”

Mission Grafica is in the realm of screen printing that is only the starting line of what this art medium has to offer. From here, its world is a scatter shot of different characters, ideas, and aesthetics. The posters created capture the essence in which it is meant to pay tribute to, whether it is a band, a movie, an emotion, or a movement. But regardless of which direction screen printing floods into, it seeps back down to its truest sense of what Diaz-Infante and many others believe: access.

It is Thursday night in the Tenderloin. People are shuffling in and out from one gallery to the other; complementary PBRs and Gnarly Head Merlot in plastic glasses in the left gallery in the back, prints for purchase in the right gallery, with an unrelated hair salon nestled in between.

This is Spoke Art Gallery on Sutter Street, where just a few hours earlier, people lined down the block for the gallery doors to open at six so they can receive their free exclusive Tim Doyle print.

This is the Austin-based screen print artist’s third solo show at Spoke Art in the last three years. Each time, it is the same theme: “Unreal Estate.” Doyle, whose resume includes producing work for the widely popular Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, pays homage to television pop culture by reimagining iconic landscapes seen on the mini screen. Spoke Art Gallery Owner Ken Harman says that with this type of show, the appeal is universal.

When Harman was manning the drinks station in the left gallery, an older black man with a grey beard approached him to top off his wine glass. After their small conversation, he realizes that the exchange just proved his point.

“That dude right there, perfect example,” Harman says. “He does not know what Adventure Time is, but knows what Sanford and Sons is. That is a pretty big cultural divide between those two things. This show has been able to draw that dude who knows what Sanford and Sons is, as well as some kids who knows what Adventure Time is, and they all come together and they all appreciate it. You would not get that if this were a normal art show, which is usually a little more targeted, but with popular culture you get a little bit of everything.”

In this particular show, a little bit of everything includes the exterior of Saul Goodman’s law office and the Red Keep castle. It includes the Smurf’s village, the Munster’s house, and Pee Wee’s Playhouse. It also includes The First Church of Springfield and the Robot Arms Apartment complex.

One of the patrons of the gallery opening noticed a similarity through the use of iconography employed by famous artists of decades past, particularly Andy Warhol.

“It seems to me that the culture is repeating in visual art, but it’s doing it through illustration, and a little bit of fine art,” says Evren Bilgilham, who is also an Academy of Arts student. “These days, our iconography is visual media. It’s film. It’s television. It’s online. It’s a cycle. It’s the same type of thing that was going on in the seventies, just a completely different medium, and a different visual motif.”

And with free exhibit openings like this at Spoke Art Gallery, it is more than just appreciating the cool artwork on the walls as Harman explains. It is also the actuality of taking a print or two home.

“That’s something people aren’t used to,” Harman says. “They aren’t really aware that you can do that, that you can walk into an art gallery and go home with really cool art for under a hundred bucks. So the price is definitely nice.”

Harman started out as an art blogger, writing about the street art scene while working at Whole Foods as a bagger. But through a sequence of events, which the San Francisco Chronicle quoted Harman describing it as a “happenstance and coincidence and serendipity,” it led to Harman opening Spoke Art Gallery in 2011 “with just sort of a dream and a credit card.”

“Historically, if you want to look at the aesthetics of the Bay Area,” Harman says. “The Mission is cool, Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen, the birth of the SF street art scene, and a sort of folk art scene, definitely informs the aesthetic here, more so than it does in other cities.

“It is almost a sense of community in here. I feel more than there is other cities. I think that is in part because there is a large number of creatives, but also not a large market. We are all sort of in the same boat together. New York has a large number of creatives, but also a very booming art market that San Francisco does not have. So you do not get that sense of camaraderie between artists, and I feel it is a little more competitive in places like New York and L.A.”

That idea of camaraderie and community is not far off. Though the Tim Doyle’s Spoke Art show was a solo venture, the gallery also curates shows that feature a wide-array of artists focusing on a theme. One such theme is the annual Bad Dads show, which is based upon the works of film director Wes Anderson. Outside of the walls of Spoke Art, there’s even The Rock Poster Society in the Bay Area. This is a nonprofit organization that aims to preserve and promote the long-standing relationship between music and the graphic art.

“The Rock Poster Society are like the keepers of the crypt,” says Oakland-based screen print artist Matt Leunig. “They keep the flame burning for the old school stuff.”

Founded in 1998, the organization holds an event for artists and poster enthusiasts to meet each other, and buy and sell posters in San Francisco each year. Leunig, who did his first The Rock Poster Society Festival of Rock Posters show six years ago, says that most of the old school poster artists who created posters for venues like the Fillmore in San Francisco are still a part of the group.

“You will be sitting across from someone like Stanley Mouse,” Leunig says. “It’s insane because you are in the same show with the old school guys who started it all, who are very humble, and cool in this very low-key atmosphere.”

Like all of the artists in The Rock Poster Society, Leunig’s work primarily consists of gig posters—posters created with the sole purpose of promoting a band playing a venue ona particular night. Some of the musicians he has worked with include Ween, Erykah Badu, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and the Pixies.

“The art form of screen printing is really hot right now,” Leunig says. “There’s been a resurgence of going back to hand drawn, hand made artwork. It’s a digital backlash. You can find a cool picture and save it as a JPEG. But if you have that same image, that you know somebody made by hand, it means more because when you look at it, it’s a piece of art.”can find a cool picture and save it as a JPEG. But if you have that same image, that you know somebody made by hand, it means more because when you look at it, it’s a piece of art.”

Berkeley-based screen print artist John Howard, who is also a gig poster artist in The Rock Poster Society, agrees that there is a digital backlash as Leunig describes.

“There’s no longer anything tactile related to the music” Howard says. “People wanted something to replace the LP that you used to hold while you listen to the music. It’s kind of hard to say or expand it from that, but it has gotten crazy in the last several years.”

Howard has created work for bands like Sonic Youth, Queens of the Stone Age, and Sublime. Despite mass producing their work by the hundreds and selling it for less than three digits, the resurging screen printing medium has seen a new audience give rise: the collector. Howard says he does not play to collectors that much.

“I don’t want to do a hundred posters and be at the bottom of some collector’s drawer,” Howard says. “I’d rather have it go to people at the show that love the band. That’s why I do it. I want it to be on their wall because they love that band. I’d rather have it take two years to sellout of a poster than have most of it go to that.”

Leunig, at one point, had to be much more particular as to who gets a special black and white String Cheese Incident print of his. The posters were meant for children to color on their own, after which their parents send back photos to Leunig. Unfortunately, Leunig caught someone trying to flip the poster on Ebay.

One of the other effects of the resurgence is Flatstock. This is a poster convention of sort that the American Poster Institute organizes to feature artists around the world on a convention platform. The American Poster Institute—like The Rock Poster Society—is another nonprofit organization that serves the poster community, but on a broader scale.

“There should at least be a Flatstock here,” Howard says. “I know they tried a couple of times, but they haven’t been that good for a couple of different reasons, but not because they couldn’t be, mostly just logistic kind of reasons. San Francisco should be the epicenter of psychedelic art. It could be and have a great history to back it up.”

Both Howard and Leunig attended Flatstock at the weeklong South by Southwest conference in Austin, Texas in March.

Oakland-based artist Jason Munn also attended Flatstock this year. However, compared to Leunig—who uses large fields of color a key line to keep everything connected—and Howard—whose works have a traditional psychedelic rock poster look that’s quintessential to San Francisco—Munn is the complete opposite.

“When I first started, my stuff had this minimal look, even though it doesn’t look like it does now, but you can tell,” Munn says. “Especially with the way I work with type and stuff. It was quiet and I like quiet. And a lot of the bands that I was doing stuff for were very quiet bands. This was the kind of stuff that I was attracted to. And minimal, definitely, you can describe some of the bands like that.”

Some of the bands he has worked with includes Death Cab for Cutie, The Postal Service, and Phantogram. Munn has even been commissioned to create a line of retail projects for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Artist Series in 2011.

“I really like mid-century design work; simple and economical, straight lines, minimal use of color. Very un-rock and roll for the most part,” Munn jokes. “With John Howard and Matt, I love that they have that traditional feel. They all require a different way of thinking. I can’t think the way those guys think. I’m always kind of amazed about what these people do.”

These people, and so much more, make or break those in the screen printing universe. They come from different backgrounds and it reflects in what they produce, whether it is a band poster, a gallery, instruction, or appreciation. The audience, to which they serve, may not ever overlap.

But regardless of the theme or subject matter scraped through the flooded yellow silk screen and on to the flatstock poster, each of these artists, instructors, enthusiasts, and gallery owners essentially believe in the idea behind why they print, sell, collect, or teach. It is the same ethos learned from the screen print shop in an attic in the Mission.

“Screen printing is supposed to be the most democratic art form; it is about people having access to information and to work,” Diaz-Infante says. “It’s not like only one person can only own this one piece. No, you make five hundred and everyone can own it and see it.”