By Victor Rodriguez

Photos by Nelson Estrada

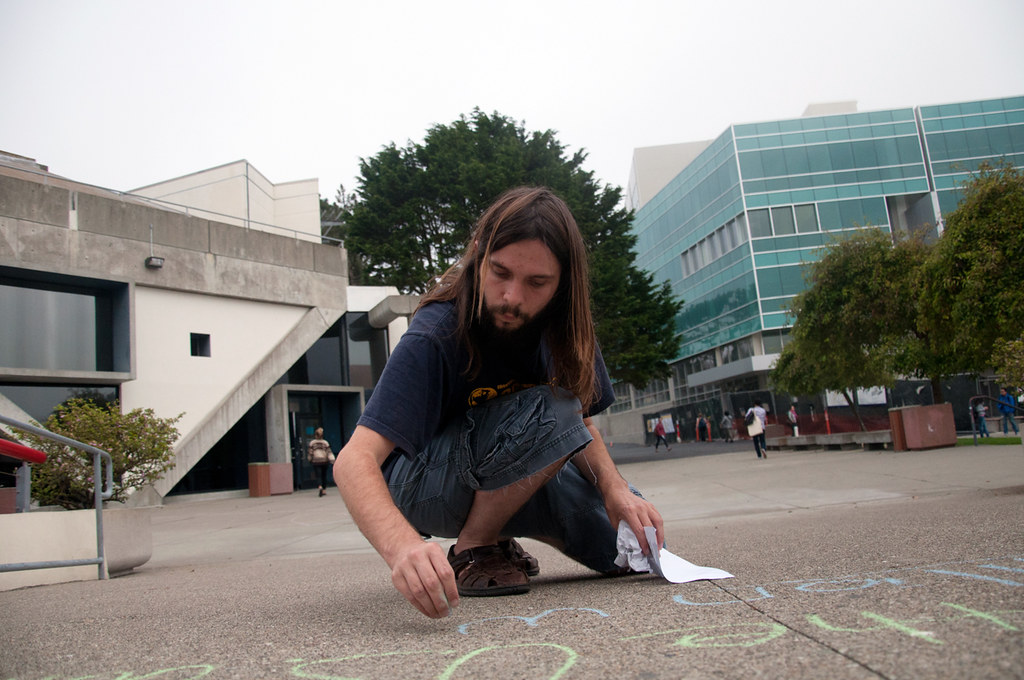

Walking on broken asphalt and descending pathways, the voices seem to get a lot louder. The people passing by at first just read their books in the sun and sit on the grass, but as Sproul Plaza comes within view, a different set of people are seen on the open space and most popular area of UC Berkeley. These are people holding up signs and banners, with red bands on their arms and chalk in their hands. On this day, many groups join together, including an effort from SF State, to show support by waving banners and raising their fists in anger against the proposed tuition increase of eighty one percent. This story is not only familiar for SF State, or California for that matter, but the whole nation. With various organizations coming from different backgrounds and a multitude of political ideologies, they all share a similar view: Tax the rich and strengthen the working class.

He walks into the empty class located at Burk Hall 226. As soon as the chairs are rearranged in a circle, he sets his black coat on his chair and pulls out a pen and black notebook from his messenger bag. With attentive eyes, he focuses in the direction of where the economic information is coming from. While he writes, a circle of about twenty students are introduced to a familiar idea that seems to push away the economic troubles they seem to know all too well.

The meeting is entitled “Stop the Budget Cuts: A Socialist Perspective,” and the socialist concept is the same one that was introduced for uniting the common workers for equal opportunities by Karl Marx. Before the meeting begins, twenty-five-year-old Terence Yancey says, “The idea of this organization is to give students a voice, to organize independently and fight against the economic problems of capitalism.”

Capitalism, in a general sense, is the idea of privately owning means of production for the purpose of profit, usually taking part in competitive markets.

Capitalism, in a general sense, is the idea of privately owning means of production for the purpose of profit, usually taking part in competitive markets.

In collaboration with the Socialist Organizer, Yancey, a philosophy major, seeks to organize dedicated students toward speaking out against the budget issues in schools, and specifically in universities. In documents, flyers and literature made available at the table behind the circle, the Bay Area branch of the nationwide organization explains what socialism is and how it can be practiced to resolve this particular problem of deficits in schools, among other things.

Within the United States, it is not strange to believe that socialism has been historically downplayed by mostly right-wing political figures such as the Tea Party and US presidents during the time of the Cold War.

“Socialism is mainly a form of critical thinking,” says James Quesada, an Anthropology professor at SF State. “But historically [in the US], its been given a negative reputation and there’s a misunderstanding on how the [socialist] power operates.”

“Generally, there are a lot of misconceptions about socialism,” says Yancey. “A lot of people associate it with Stalinism. For example, what the Russian Revolution was supposed to be and what it turned into,” explains Yancey, referring to Harry Ring’s article, Why You Should Be a Revolutionary. The article elaborates on how figures that represented the Russian Revolution were on trial in Moscow, labeled as enemies of the same revolution by Joseph Stalin.

“A capitalist system only works temporarily,” says Yancey. “They give to programs and services in times of surplus, but they cut the same ones as soon as things are bad again.” Yancey references the New Deal program of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, which in a similar way, sought to give the majority of the population new economic opportunities through relief, recovery, and reform. Some examples include the Wagner Act of 1935, which promoted labor unions, and the Social Security Act, which is still active today. However, due to the focus on World War II industries and drafts, the Republican Party shut down various programs like the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps once they held the majority in office again in 1938.

Different recessions throughout the American timeline have since affected American economy as well, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s. These include the oil crisis of 1973 and the recessions faced during the early Reagan years in 1981 and 1982, which affected mostly small businesses.

After the second meeting, Yancey discusses the agenda for the group and how they can get their name out. He collaborated with the group to come up with the name, “Students for Social Justice.”

Because of apathy or political agitation, this is not the first time that college students have confronted the repercussions of budget cuts and rising tuition costs, nor will it be the last for the time being.

Because of apathy or political agitation, this is not the first time that college students have confronted the repercussions of budget cuts and rising tuition costs, nor will it be the last for the time being.

Considering the circumstances, the problem with such a high cost for higher education not only leaves out potential applicants, but also causes a grand scale of disillusionment among the ones already attending.

Back in the Fall of 2009, students attending SF State received an email in late July that described the increase in student fees. Full-time undergraduates alone had to come up with 2,370 dollars. Two years later, this same group now has to pay 3,178 dollars, according to that same annual email that was received around mid-July this year.

The effects of military spending also continue to take a toll, with approximately eight hundred billion dollars being funneled to the military around the world each year. The US government has half that amount up for budget in the coming year, rendering more than a billion a day, according to research done by the Revolution Youth International.

The Socialist Organizer describes proposed cuts by California government, with five hundred million dollars being cut from the CSU system.

The effects of military spending also continue to take a toll, with approximately eight hundred billion dollars being funneled to the military around the world each year. The US government has half that amount up for budget in the coming year, rendering more than a billion a day, according to research done by the Revolution Youth International.

The Socialist Organizer describes proposed cuts by California government, with five hundred million dollars being cut from the CSU system.

In one way or another, students have had a negative run-in with this recent economic trend, but the noticeable thing here is that they are all students of different years. It is not only juniors and seniors enduring the hardship; they are students that come from any college and any background, trying to find ways to make their unique situation better.

“This is not the only organization we have, and we do not stand alone,” says 26-year-old Eric Blanc, another organizer and student at City College of San Francisco.

“We seek to join the same causes as other organizations for the common cause of preventing this crisis to keep from going further.”

“We seek to join the same causes as other organizations for the common cause of preventing this crisis to keep from going further.”

Some of these students pay for school out of their own pockets, others look to obtain loans, and many have been denied some form of aid, but they are all searching for a way to make their heavy transition easier.

For socialist organizations, their goal is to obtain equal opportunities for those who work and produce for the benefit of the population. In this case, for the Students for Social Justice, the same principles of socialism applied to education would mean giving educational opportunities to anyone seeking to pursue their aptitude for the betterment of society.

The way to do this would be to allocate the funds of the university toward educational resources for students (making tuition free) and adequately paying teachers. Private property would still be present, but it will serve the community. However, the battle for this objective can arise from any group of any alliance or ideal. “It does not necessarily have to be a socialist group,” says Blanc.

Likewise, Quesada tells us that the idea of socialism is only one way to think with more options toward the construction of our way of living. “It’s a competing political ideology, but it offers alternative ways toward socially and economically arranging our lives,” says Quesada. “One example is like the European social democracy, which provides welfare for all its citizens.”

In a meeting one day before the student protest at Berkeley, Yancey let the Students for Social Justice know that they will make an appearance and protest alongside other groups and students to show solidarity from university to university. This day acts as a reckoning for their movement.

On September 22 beginning at noon, voices ring loud through the speakers. The speakers of various social groups stand side by side and deliver their speech, one by one, into the microphone as their ideas and collective rage flourish to an estimate of over four hundred people.

“This is a first step in getting people to be aware,” says Blanc of the crucial reason for having protests like these and having many organizations educate the masses on an assortment of perceptions for solving the economic problem in schools.

With many banners showcasing what they represent, as well the various tables with sign-up sheets and informative reading material, other representatives hand out their documents.

With many banners showcasing what they represent, as well the various tables with sign-up sheets and informative reading material, other representatives hand out their documents.

Thirty-one-year-old Charles Jones hands out a blue paper that explains what politicians are doing to try and solve the budget crisis; cutting programs and other funding as well as imposing new taxes on those already affected, which is the working class.

“We all need to understand that workers’ wealth are going to the rich,” says Jones, a former teacher in Massachusetts who would sometimes work as a private tutor. “We need to tax the top richest people, the top one percent in California alone.”

Jones represents a campaign for “Tax the Super Rich,” whose primary focus is its title. He explains that with so much money that business executives and other rich figures have, nothing is really being done with it and that money is just sitting there.

“This is money that needs to go towards education, healthcare and infrastructures,” says Jones. “Contributions from the rich for higher education is only at seven percent, the rest mostly comes from the people.”

“This is money that needs to go towards education, healthcare and infrastructures,” says Jones. “Contributions from the rich for higher education is only at seven percent, the rest mostly comes from the people.”

According to the flyer, the top one percent of the richest Californians, or approximately 150,000 people, have a total income of 255 billion dollars. More than three times the whole state budget for the California population of forty million people.

If the problems were not so great for people going to school in-state, other students pay a higher price trying to get quality education. With no chance of financial aid because she comes from Idaho, Jashvina Devadoss, a freshman at UC Berkeley says, “I pay out-of state. My dad has to help me in coming up with about fifty thousand dollars.” A curious figure seeking to understand where the battles can be fought, she wears a red arm band and marches with the crowd, raising her fist and chanting along.

After the heat and passion has riled up so many students, the march begins and paces past various buildings, where professors, administrators and other students would peek through the windows. They chant loud and in sync, “The workers united will never be defeated!” And continue with a call and response, “What do we want? Free education! When do we want it? Now!”

Attempting to enter and occupy Tolman Hall, a study and reference building, some of the protesters are shoved violently out of the way by campus police, while some protesters even take mace in their eyes. Eventually, the mass overcomes the ten or so police authorities and stands inside the building reiterating their chants several times.

For organizations like these, the repercussions evident from this simple collective protest stem from the capitalist system and the concept of private property. Karl Marx wrote about this concept in his work, and it is constantly referred to by these organizations. His theory states that a socialist movement is a historical necessity and is the work of a proletarian revolution, which is formed by the working class who are also the majority. Considering that a small minority control the workers’ wages as well as funding for programs, a workers’ revolution will occur when wages fall, programs are cut and the capitalist system pursues military aggression. He labels them as the bourgeoisie, otherwise known as the upper class.

For organizations like these, the repercussions evident from this simple collective protest stem from the capitalist system and the concept of private property. Karl Marx wrote about this concept in his work, and it is constantly referred to by these organizations. His theory states that a socialist movement is a historical necessity and is the work of a proletarian revolution, which is formed by the working class who are also the majority. Considering that a small minority control the workers’ wages as well as funding for programs, a workers’ revolution will occur when wages fall, programs are cut and the capitalist system pursues military aggression. He labels them as the bourgeoisie, otherwise known as the upper class.

According to this socialist perspective, the policies that are approved and that affect the cost of going to school can be eliminated by running it under the basis of socialism, which would prompt attendance to be free for students because it would be state-owned and operated, especially since it is a public institution. For Quesada, when push comes to shove, the state needs to intervene and take responsibility for the benefit of the people. “Even in this school, they want to privatize it,” he says, emphasizing the irony.

In response to why students should rise up and organize against the institutions they are a part of, Yancey says, “We as students have the power to act collectively and have our demands met.”

whoolo • May 24, 2016 at 7:40 pm

Simply wanna input that you have a very decent site, I like the style it actually stands out.