Written by Lauren Manary

To the members of this community, “hacking” isn’t just for girls with dragon tattoos, geeks, or Guy Fawkes-masked activists.

“It’s the out-of-the-way of looking at things,” says Mitch Altman, one of the founders of the hackerspace. “It’s not being afraid to take a radical approach. Someone who is a hacker isn’t afraid if their government makes laws, because they won’t think they’re important.”

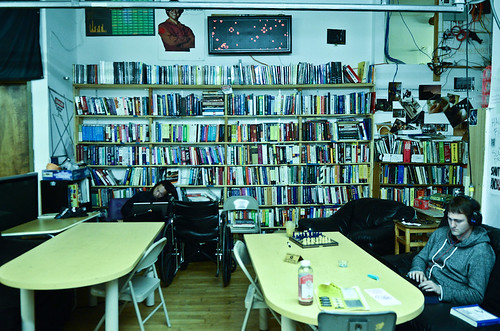

Some hack computers, but others hack food and photography: to the members of Noisebridge, it is about challenging the fundamentals of creative projects. The physical space is impressive: 5,200 square feet broken up into several areas dedicated to one craft or another. Computer chips and hardware are littered about, colorful wires dangle from labeled drawers. In one corner, mushrooms are beginning to sprout and kombucha brews. In another, a hacker known as Rayc dons protective goggles and sparks spray around him as he sands something down. Another hacker, Jared, ignores the weekly meeting, instead choosing to tinker on what will become a Tesla coil. Everyone around is moving, creating, or brainstorming. The sound of clicking computer keys never stops.

What is this space of creative chaos? Noisebridge and its members are part of a growing number of “hackerspaces” in the world. These spaces are meant to provide a safe place for hackers to collaborate and socialize, typically in the field of technology. At this space in particular, members offer free workshops for affiliates and the public alike. Altman gives a weekly soldering workshop on Mondays but the space offers a variety of other classes from sewing and “zine” production to German lessons.

This community has been sometime in the making. What had started as a small group of self-proclaimed “dorks” meeting in cafes has become a swelling technological dynamo with a pinky in the “Occupy” pie. Their mission? To provide infrastructure for technical-creative projects in the community.

They used to be lucky if they had fifteen people at their meetings. But, in the last three weeks they have had more than two or three times that. Meetings that are supposed to last at most an hour now run into two. Their funds are at the highest they’ve ever been. But there seems to be a degree of unrest on this particular evening. The hackers, some old, some new, have found themselves at a crossroads.

Kelly Buchanan, the treasurer and neuroscience researcher at UC Berkeley, warns another that this meeting is probably going to be an abrasive one.

“It used to be that our community was small enough that we knew everyone who was around,” she says. “It’s not like that anymore.”

Some members say it was the Occupy movement and their involvement with subgroup “Hackupy” (pronounced “hack-u-py”) that has led to the sharp spike in attendance. But do sheer numbers equal success? Some of the veteran members are not so sure.

It was clear that many of the comments were pointed attacks. There seems to be a literal and figurative divide in the room. Some sit in the inner circle, and it’s clear those are the veterans. Many have hacker nicknames: Snail, SuperQ, Zephyr, and Mike the self-proclaimed “Technowanderer.” Others spread themselves around the room, less tightly-knit and seemingly more detached from the meeting. The divide was physically clear. Jesse, a veteran, chose to address what everyone was thinking: who is a “real” hacker, and who is taking advantage of their free space?

“It is because of these people corrupting what Noisebridge is about,” says Jesse, a middle-aged hacker and potential Allen Ginsberg impersonator. “If you’re a hacker, you hack! If that’s not what you’re about, then you should leave.”

Others are much more fatalistic.

“More people are leaving than coming,” proclaims Miloh Alexander. “Noisebridge will be gone in six months!”

The crowd groans and seems to unanimously disagree with him. Tom Lowenthal, a young British transport who makes his day job at Mozilla, struggles to call the meeting to order and mitigate some of the tension. Members and non-members begin to talk over one another. It is clear, this group is experiencing a bit of a shake-up. Should the group continue with its historic “everyone-is-welcome” mantra? Or will it become more exclusive?

But with their success has come a fundamental question: what is hacking?.

The group comes to a consensus: no more “undesirables.” Jesse points to a girl named Amber, and asks her to explain herself. He argues she is no hacker but is simply using the kitchen and bringing in her homeless friends.

The girl looks nervous. She slowly stands to face the crowd and deliver her plea.

“To me, hacking is learning and going at it and creating going into that,” she says. “I am not a computer hacker but I do use my own computer and I hack astrology and anyone who wants to learn more about that can when they sit with me.”

It is clear she is not wholly accepted by the crowd, and neither are her ideas about astrology. The debate continues. Some say the Occupy movement has a tendency to attract homeless people and “street kids,” who have now started coming into Noisebridge. It is these people in particular, it would appear, the hackers are most concerned about.

Just then, a man from the Occupy SF movement barges in. He interrupts the meeting, proclaiming the movement has provided them with nearly 600 pounds worth of food that will be delivered momentarily. It seems to distract everyone from the general tension in the room.

This isn’t the Noisebridge that Altman had imagined.

He is easily recognized by his long curly white hair on one side of his balding head, the other dyed rainbow colors. It isn’t surprising to find out that Altman used to organize urban communes, considering his particularly funky hairstyle. Searching for a sense of community with other hackers and nerds, Altman frequented hackerspaces and hackathons for years before starting Noisebridge.

This hackerspace is the brainchild of two hacker heavyweights: Altman, one of the first developers of virtual reality, and Jacob Appelbaum, of Wikileaks fame and a world-renowned security expert and hacker. The pair first met at the first Maker Faire in 2006, a Bay Area DIY festival, when Jacob approached Mitch about his invention, TV-B-Gone, which can remotely turn off televisions in public spaces.

The two became friends and imagined a space where like-minded people could gather and promote one another, and do it for free. They sent the message out through their respective networks, and the message spread like wildfire. By Sept. 2007, more than 30 people were attending Noisebridge meetings in cafes every Tuesday. But the pair imagined an even greater potential — a physical space to really develop a hacker community.

“I was thinking, wouldn’t it be amazing if all that energy were paired with workshops and classes and were all day and night in my hometown?” says Altman.

A year later, they had their hackerspace. Soon, they outgrew the space and moved to their current location at 2169 Mission Street.

Positioned between 17th and 18th Streets, the hackerspace is sandwiched between a fruit grocer and apartment buildings. The only indication of their presence is a symbol hung above their gated entry: a red and black badge. All who enter are under the surveillance of the front door camera that leads to a closed circuit television upstairs by the buzzer. Access is only granted via key for more senior members; all others are buzzed in.

Appelbaum has since left and has been called upon for his security expertise and hacking skills all over the world. He says he is often detained by authorities when flying internationally. Altman, on the other hand, says he is perfectly happy spending most of his time at Noisebridge. He believes it is his calling.

“We all have the power to make our lives better and make the lives around us better and make the world better. It’s incredibly rewarding but you have to be ready to fail, fail big, and fail a lot. But we all have the power to do this,” Altman says.