When you were young and green and didn’t yet earn an allowance or have a cellphone, losing your teeth was a rite of passage and fiscal gain. It could be bloody, and painful and weird—or worse, swallowed—but holding up a little piece of yourself that would somehow transform into a five dollar bill was an American kid’s first taste of capitalism. Grinning ear to ear with a gap to stick your tongue through was the first taste of cool. Unfortunately, the novelty wears off once all the big girl teeth come in.

Imagine you’re at the perfect party or social gathering where you are trying to mingle with people you consider datable and good-looking. Your favorite drink is in hand, and your eyes scan the room for someone who will look back. No, no, no, yes. This person is breathtaking but they do not see you yet. Finally, they do, and your feet start taking you toward them before you realize what’s happening. They turn their head, and their front face is just as good as their profile, except—what the hell is that? Where there should be four front top incisors, there are only three. Suddenly all you can see is the gummy abyss. It must be translating pretty badly on your face, because the allure is gone. The charge in the air has dissipated. Their mouth snaps closed, and they run.

Teeth are also some of the most visible and tended to parts of our bodies by health care professionals, and those post card appointment reminders were foreboding of the scraping and poking and “are you flossing?” to come. Most children see their dentist twice a year until they reach adulthood, 84.6 percent for Americans as of last year. However, as people age, the incentive to let a hygienist make you bleed and chastise your brushing technique wanes, and adults visit the dentist less frequently than their physician. According to data collected by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016, compared to the 84.6 percent of adults who visited a doctor or health care professional, only 64.4 percent of adults visited the dentist. About one in three adults were also dealing with untreated dental maladies.

And evidence can be found that the loss of a tooth has impacts far beyond the mouth. A study conducted by researchers at the University of Messina, Italy, found that “both physical and psychological aspects of oral health were significantly linked to mood states,” suggesting that oral health can be linked to bouts of depression, anxiety, anger, confusion, and fatigue.

Dr. Joy Morris has been practicing dentistry in the Bay Area for twenty-five years. She has stuck her gloved hands into all kinds of mouths for all kinds of reasons: fillings, cleanings, molds, extractions, root canals, crowns—the works. Her teeth, unsurprisingly, are cinematic levels of straight and white. In her experience, losing teeth sucks.

“We identify with our teeth,” Morris says. “It’s our face, when you talk to people. It’s so much deeper than cosmetic, it’s psychological. A young person with good teeth without a front tooth would be shocking.”

Teeth, or lack thereof, change what’s in the mirror and what strangers on the sidewalk will think to themselves. Teeth themselves are not often the subject of research on personal presentation and self-esteem, but those that do rely on distributed surveys and personal feedback. The British Dental Journal conducted such a survey almost twenty years ago and found that forty-five percent of responders were emotionally impacted by the loss of an adult tooth, and fifteen percent, over a year later, had yet to get over it.

But none of these people were under thirty. Findings from the Italian study, “Clinical Psychology of Oral Health: The Link Between Teeth and Emotions,” suggest that “the oral compromission of adolescents and young adults could be tied not so much for the physical aspects, such as pain or discomfort, assessed in this study, but above to other oral health aspects belonging to the general health QoL (quality of life) such as dental aesthetics perceptions and dysmorphic levels.”

This suggests that tooth loss and crises impact young people’s emotions more profoundly than people of their parents’ generations.

Kylee Piper, twenty-four, would agree with Morris. Piper recently had eight veneers installed on her top front teeth, a twenty-thousand-dollar procedure she says was “the dream I never thought would come true.”

While Piper had straight teeth thanks to braces, they were not “perfect,” and plagued her with insecurity despite insistence from others around her and a high school “Best Smile” superlative. The TLC network’s reality program “Toddlers and Tiaras” would inspire envy in her when the pageant contestants wore their “flippers,” a kind of mini denture to display perfect pearly whites when the girls would take the stage.

“I’ve always been a very smiley person and while everyone thought that, it was always such an insecurity for me,” Piper says. “I remember it going back to when I was very young. I work in a client facing job, and sometimes I would notice people in interviews. Maybe they weren’t staring at my teeth, but I always thought that they were.”

Six appointments and a bit of whittling later, Piper had eight new hand-sculpted chompers and her sense of perfection.

“I really didn’t think people would notice. Someone asked me if I had a nose job because my face looks more even. Every person sees perfection as something else, and that’s what makes individual people beautiful.”

Kids are cruel and vulnerable in equal measure, especially with obvious visual differences. Clayton Bradley was fourteen when he found out his top left incisor was never going to come in because it did not exist. What’s more, the periodontist wouldn’t be able to give him a permanent tooth until he was twenty-one and fully grown.

“It was an odyssey,” he says, and laughs.

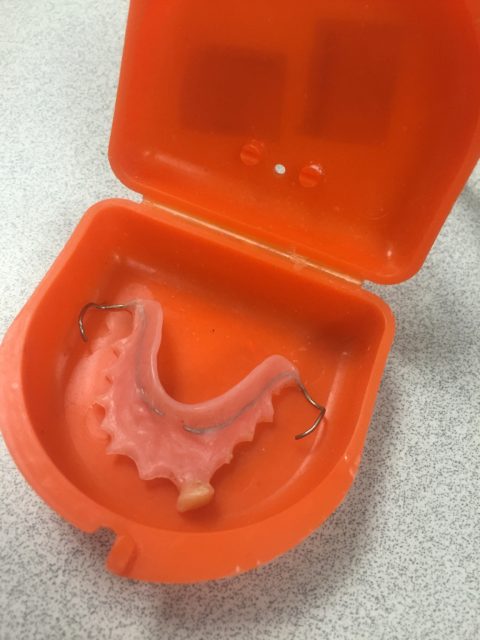

Bradley has used various forms of false teeth and self-protection over the years, but even braces, a Maryland bridge (a false tooth rooted with metal to the surrounding permanent teeth) and a stayplate retainer were not enough to stave off adolescent cruelty.

“I got a lot of hillbilly and incest jokes,” Bradley says. “People would always ask me what happened, blah blah blah. I remember we were at this study abroad fair, and I was talking to these people, and we were eating. I’m not gonna take my tooth out and be eating food and talking with this huge hole in my face.”

He can laugh it off now, but his mother, Tanja Kor, notes he wouldn’t smile with his teeth for many years, until the permanent tooth was implanted. His lack of tooth is one of his mother’s genetic hand-me-downs. She was able to correct her gap with adult braces, but she admits she worried incessantly about her son’s emotional well-being.

“If I had to go through that as a teenage girl, it would have been horrific for me. I’m Dutch, and my Dutch relatives think Americans all have two things: guns and perfect teeth. I knew there was a certain degree of self-consciousness because he was smiling with his lips closed. He got really good at hiding it. In this country we are obsessed with perfect teeth.”

Here’s where things get personal. Without knowing, I became that one in three adults. At twenty-three, a series of appointments unearthed an untreated dental problem, despite my biannual visits in the pea-green chair. I lost my front tooth, tooth number twelve, almost four months ago. Well, I did not lose it; it was forcibly removed from my skull. It took three different oral health professionals–a dentist, root canal specialist, and oral surgeon–to discover I had been born with a “lingual groove,” a canal of sorts running the length of my tooth. A canal that caused a bacterial infection no one could detect was happening for a year. So, once it was discovered, it was past the point of no return. The tooth had to come out.

I cried for days. My dad’s family is from England, and throughout my bouts with dental hardware he would apologize and repent for passing his misaligned mouth to me. I had spent three years with braces, and was still using my retainers from high school almost every night. I had worn headgear, rubber bands, springs. I believed that all my oral trauma was over. Alas.

They took a foul-tasting mold of my mouth and fitted me for a new retainer the week before the “extraction,” as if there was an attributed value in what I was told was a “biohazard.” My new tooth was waiting for me next to where they would lay my old one once it was out of my head. They said there would be pressure, but no pain, sounds of crunching but, due to the drugs, it would feel like an out of body experience.

I still cannot identify everything I was feeling during the ordeal. I stared at the ceiling, off-white and lacking the decorative embellishments of my pediatric dentist’s when I would get a cavity filled. Time ceased to exist. There was only before and after.

Once it was removed, the infected tissue within my mouth was scraped out, filled with bone powder and sewn up with dissolvable stitches. I know they did all this because due to a pre-existing condition, I could not be unconscious.

The bone powder, I was told, was to fill the hole so my teeth wouldn’t start shifting, and to help my body start regenerating its own bone. A small silver lining, I guess, is that I am kind of an

X-Men character.

What happened after that is a nitrous-induced blur of drool, codeine-laced Tylenols, and five days of a liquid diet. I couldn’t eat chips, hard bread or any food with hard edges for the first month, and would compulsively rinse my new hole with the medicated mouthwash they said I only needed to use twice a day. It was more like five, but the burning sensation of sterilization trumped the shameful agony of an abscess, and the fear of a returned infection.

The retainer with a fake tooth attached, called a “stayplate,” is to keep my teeth in position, but also to keep my emotions in line. It’s so I can go to work without watching customers flinch when I smile. It’s so I can go to a party without a drunk guest pointing and laughing “You ain’t got a tooth! She ain’t got no tooth!” Yes, that really happened.

I developed a small lisp due to the swelling and the renewed awkwardness of the retainer sitting in my mouth. I had only been wearing my braces’s retainers at night since I graduated high school, and now the little orange case and its plastic contents followed me everywhere, and prolonged all my “s’s.” I also had a boyfriend that valued me far beyond my physical worth, who insisted I was beautiful, that I was “ruthless and toothless.”

I am three months out from that afternoon at the periodontist, where they numbed me from the nose down and I felt the surgeon lean over me to pull me apart. The first time I saw myself without the stayplate, three days post-op, I was disgusted. This morning, I thought it looked kind of cute.

I have an appointment in January to determine if my body has created enough new bone, which will serve as the foundation for a screw that will be my new “implant.” I never thought implants of any kind were in the cards, but my body decided for me. I wear the stayplate at work and most of the time at school. It comes out to eat, and sometimes I forget to put it back in. I’m thinking of getting it cast in gold, but I don’t want to stunt too hard.