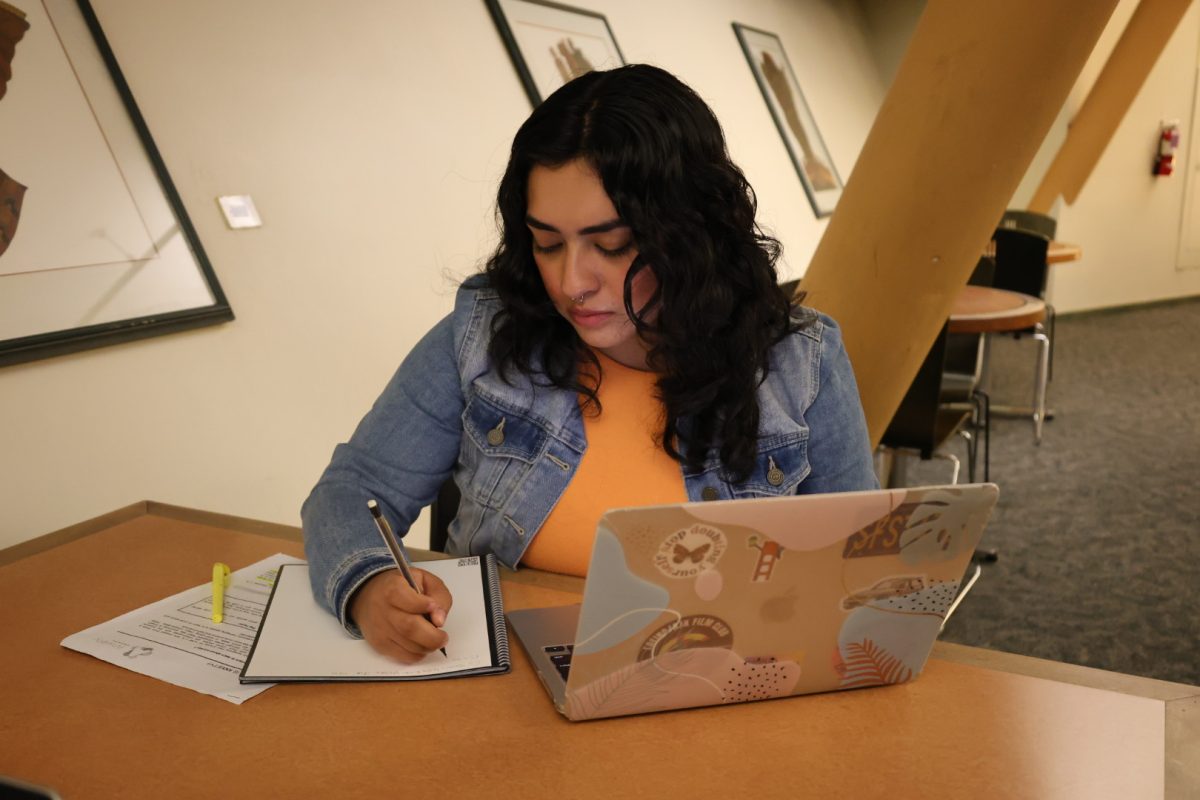

Hillary Peregrina didn’t know what to do with her feelings of depression when she was fourteen. As a Filipina-American teenager, Peregrina felt like she didn’t have a say in her mental health, and didn’t seek help for it until she was twenty-two-years-old.

“I pretty much recognized from when I was fourteen years old that I had some sort of mental illness, but I went to an all-girls high school in Glendale, California. Just the sheer size of the campus and the fact that everyone knew each other, I almost had this sense of shame and embarrassment, and I didn’t want my family to know I was going through all of this. I didn’t want it to be a reflection of my parents’ character and I didn’t know who I could turn to seeking help now.”

What’s so worrisome about Peregrina’s story is that it isn’t an outlier. Asian Americans seek help for mental illness at much lower rates compared to white Americans.

According to a paper published in the Psychiatric Services journal in March of 2019 by psychiatrists such as James Chen from Harvard Medical School, the rate of suicidal intentions for Asian American and Pacific Islander students is relatively close to that of white students, at 10.4 percent and 9.5 percent respectively.

However, the study also finds that the amount of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who reported their mental health symptoms was a paltry 13.8 percent, while 28.2 percent of white students reported some sort of psychiatric diagnosis; meaning that a psychiatrist was able to actually diagnose him/her formally with something like depression or anxiety, for example.

Peregrina, now a master’s student in the Asian American studies department at SF State, is writing her master’s thesis on Filipino/a American mental health amongst adolescents from twelve to nineteen years of age. From her research, Peregrina finds that for Filipino-American adolescents, the hesitancy to speak up about mental health problems comes from a variety of culturally-related factors, even down to things like gender roles. Peregrina cites the concept of “marianismo”—the female analogue to the concept of “machismo.”

She explains that Filipina women often have to fit into very rigid gender roles, such as women being a caregiver in the home, which is where marianismo comes to play. In Peregrina’s research, the educators she interviews would say they have female students that aren’t given as much freedom compared to their brothers or male cousins.

“In Filipina American women, there are very defined gender roles they are expected to follow that are brought on by Filipino culture,” Peregrina said. “But marianismo deals with an ideal femininity that Filipina American women are expected to maintain purity in their lives, whether this is just in relationships with other people, or specifically romantic relationships.”

She says that those ideas of femininity stem from gendered ideals of what it means to be a woman and be Filipina. Even in college, she felt shame that was rooted in her Catholic upbringing.

“The sense that if I was depressed, if I was anxious, then I was sinning against God,” Peregrina said. “It took a lot of decolonizing myself from this sort of Catholic guilt, this sense of shame and embarrassment I had toward my family, to really get myself to the point where I am comfortable seeking help.”

Dr. Tiffany Yue-Li is the clinic director of Chinatown North Beach Mental Health Services, and she sees that second-generation immigrants tend to underreport due to cultural issues, such as not wanting parents to know about their mental health issues, even if they are more likely to report mental health problems.

“The stigma is still there and I’ve seen a lot of young kids, whether they’re first-generation, or born here, struggle when they go to college and they struggle with adjusting to college life, and anxiety and depression come in,” Dr. Yue-Li said. “It’s difficult for them to come in for mental health treatment, and oftentimes they don’t want their family to know that they’re coming in. So even though they are more prone to seek services or treatment, there’s still the shame attached to the stigma of something being wrong about their mental health.”

Another culturally-focused factor, especially for first-generation immigrants, is the language barrier. It’s one thing to not know a language when you first move to a country, but it’s another thing when you can’t adequately describe your mental health in your own native language.

According to Dr. Thao Tran, the medical director for Chinatown North Beach Mental Health Services (CNBMHS), there isn’t as much of an understanding of formal mental health concepts such as depression or schizophrenia among Asian American immigrants of many origins, which are mainly Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants at CNBMHS. However, Dr. Tran and her clinic find that these immigrants can understand that they have aches and pains from trauma, or that they’re seeing ghosts. She specifically gives the example of a schizophrenic old woman in this case.

“It’s not uncommon for us to diagnose someone with schizophrenia, which is a major mental illness where someone can hear voices, see things that aren’t true, have beliefs or delusions. The conceptualizations in that patient or the family may be that they’re seeing ghosts,” Dr. Tran said. “There are ghosts in the house that are possessing her, and that’s why she’s talking to herself, that’s why she’s getting angry and hitting mom.”

The conversation would then turn to treating it as a common goal for Dr. Tran and the patient to work toward.

“It doesn’t make sense for me to say that there’s no such things as ghosts, that she just has an illness and that she just needs to take her medication. Instead, we try to figure out what is important to this patient and her family and what they would like to have help about,” Dr. Tran said. “Oftentimes, it’s something like, we need her to stop hitting her mom, and be able to go back to school. That’s really everyone’s goal. With that mutual understanding of what their needs are, we try to build a mutual language and common goal and figure out how we get there. Sometimes it means taking medication or doing x, y, and z.”

This problem also rears its head when it comes to certain perceptions of mental health treatment from newer immigrants. Jorge Wong is the President and CEO of Richmond Area Multi-Services, which provides a litany of mental health aid services to a predominantly-Asian American demographic in the Richmond district of San Francisco. He specifically points to the perception that you “pay people to talk” in a therapy-type situation, which could be considered as less effective than something more tangible like medication or surgery.

Multigenerational families have their own issues that might lead to mental health issues, such as the loss in social mobility that comes with immigration to a new country.

“For some people, they might come from a country where the father might have a decent job and they end up dropping socially when they come here because he can’t find an equivalent job,” Wong said. “They might be doing more labor intensive work compared to highly educated professions, in that sense, the father might see a social status drop, and here, there’s more opportunity for females in terms of getting a job (compared to their native country).”

Wong explains that this loss in social status changes the way that they view things like childcare, since the father might not be used to switched gender roles.

Khanh Tran is an SF State biology major and a first-generation Vietnamese immigrant, having come to America at six years old. Khanh found that cultural pressure would exacerbate certain mental health issues in students that he’s tutored.

“All I’ve seen in my life was my friends sacrificing for me to go to school, they work twelve hour jobs,” Khanh said. “they gave up their relationship for me, we lived in a small-ass house back in Southern California, all for me to go to college. And that’s a lot of pressure. And that’s a lot of pressure for me to do good.”

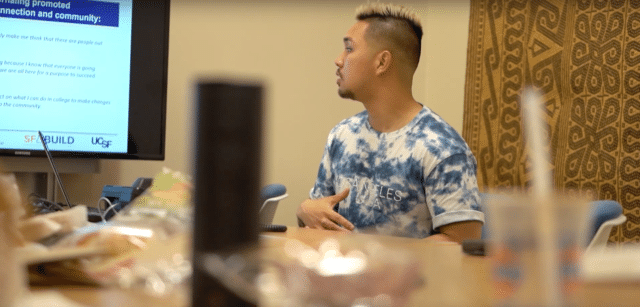

Khanh, on top of being a student at SF State, is also a member of SF State BUILD (Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity), conducting research on the impact of journaling for STEM students. Inspired by his experiences with ethnic studies, Khanh found that journaling can potentially really help students of color, citing one student that he’s found when the program was piloted in 2017.

“There was one particular student who was so quiet throughout the semester, at the end of the semester, we had a chat. He was like, ‘this is really helping me because it’s helping me confront my depression, as a student of color, trying to study a science major that was not designed for me, and it’s really hard for me to navigate,’ and they were a first generation student, low income, working two jobs just to get by,” Khanh Tran said. “But in our supplemental course, that five minutes was where he was able to really reflect on his perspectives of who we are as a student, and how he is dealing with these situations. So in a way, I think it’s really supporting students.”