It’s the first day of school, and the hallways filled with students are especially loud. While most students don’t spend months preparing in advance, some have spent much of their academic careers learning how to properly advocate for themselves in the classroom. Higher education for people with visual impairments and blindness has come a long way in recent years thanks to advancements in accessible technology, but even the most ardent students with visual impairments can still sometimes be undermined by an unwitting professor.

According to the National Federation of the Blind, about 30% of people who are blind or visually impaired attend college while 16% attain a bachelor’s degree or higher. Depending on the degree of their vision, students are equipped with different types of technology to help them participate in the classroom.

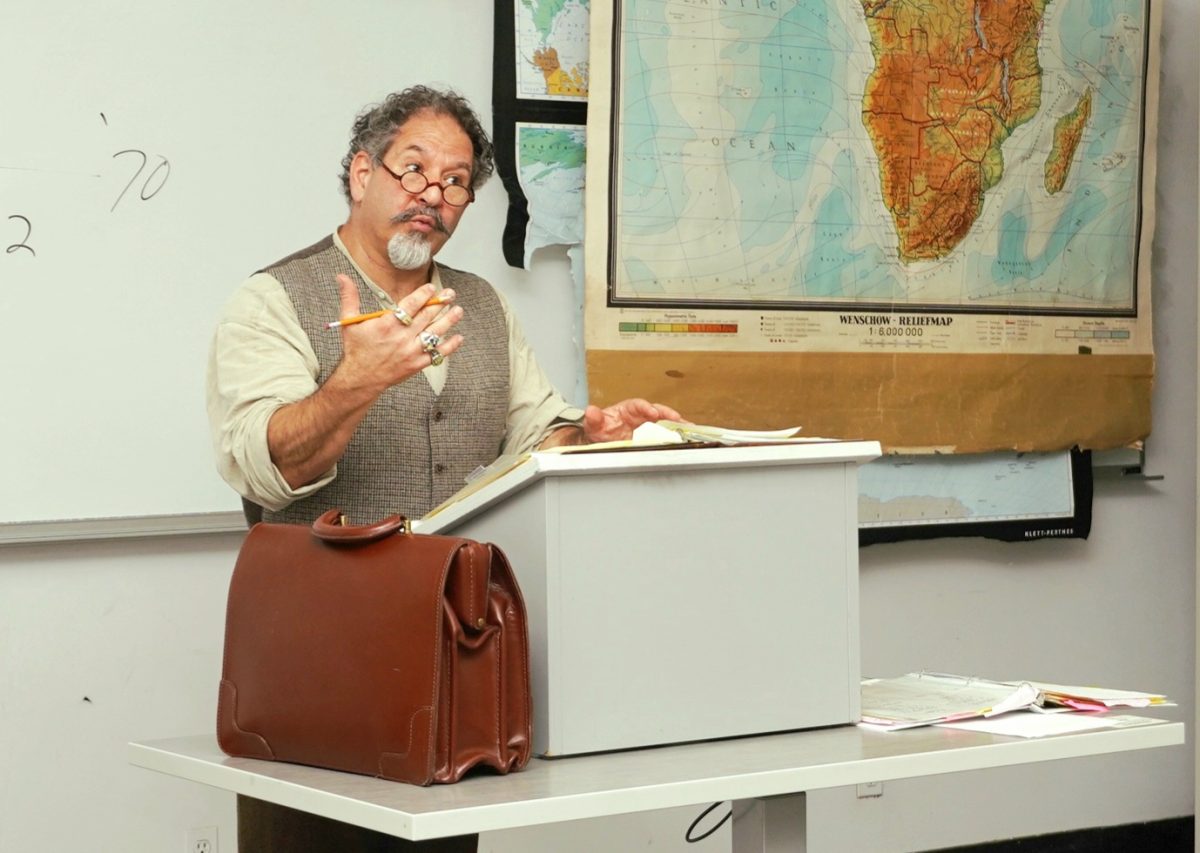

“In a perfect world, all the professors would know how to make their documents, materials, lectures and presentations accessible,” said Danny Vang, a graduate student at San Francisco State University with low vision. “I think we’re working on that, but at the current moment they need to be provided the tools in order to make that a sustainable option.Even if a professor is open and is willing to help, do they have the knowledge?”

Vang feels strongly that there is a link between society’s low expectations for people with visual impairments and a lack of understanding of their accessibility technology. In his experience, students with visual impairments use three main forms of assistive technology; braille, screen readers and screen magnifiers.

Vang began using screen readers when he was 15 years old after suffering from the sight-inhibiting symptoms of glaucoma and cataracts, but says that these conditions aren’t the reason for his low vision. Vang actually lost around 80% of his vision because of doctor malpractice.

Check out out Xpress Magazine’s interview with Vang and technology demonstration here:

Screen readers help him navigate electronic device interfaces by encoding metadata and translating it into speech. As users of the programs become more acclimated with the software’s robotic voice, many are able to speed up the narration over 50% of the initial playback settings, speaking so fast that to the untrained ear it sounds like gibberish, but to Vang and many others, going any slower would be a waste of time.

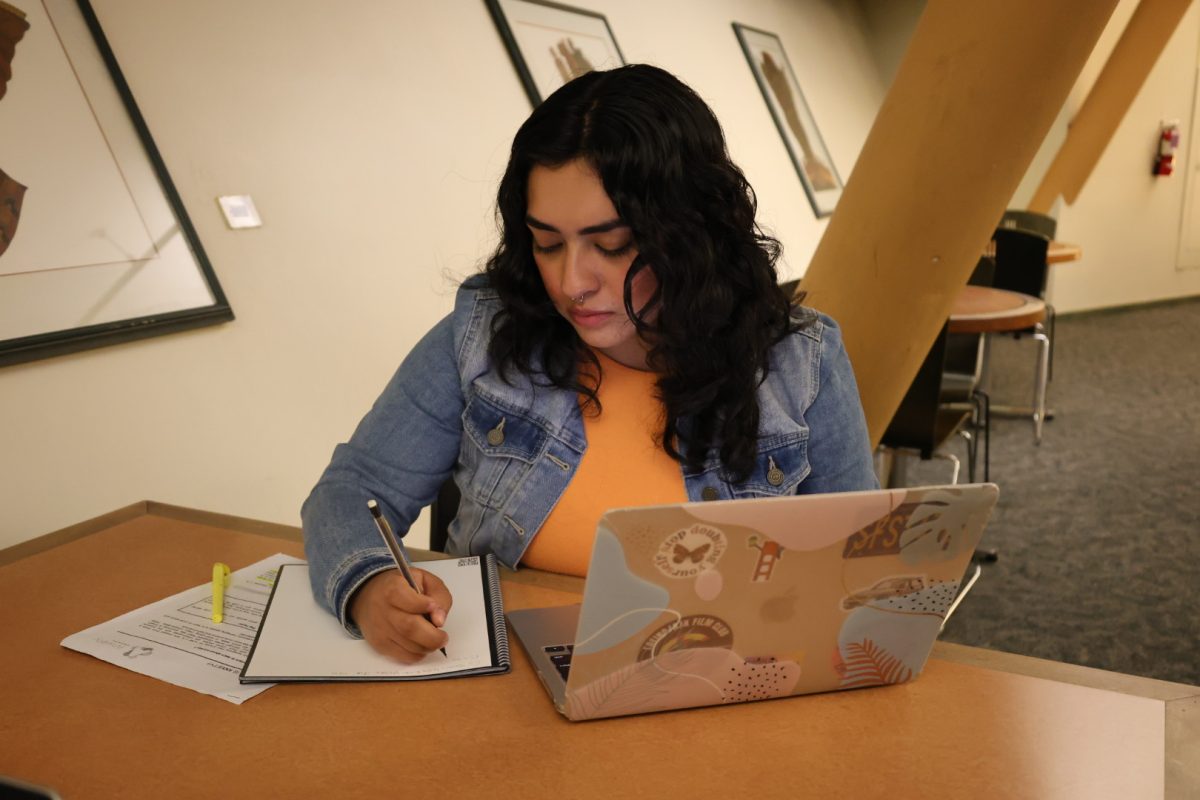

Madison Javier, another visually impaired graduate from SFSU, was born with low vision and relies almost entirely on screen magnifiers to do her work. While Vang’s condition came at a time when there was already a number of more advanced technologies available to him, Javier can recall having to haul large pieces of equipment into her elementary school classes. One device she remembers in particular is called a clarity capture video magnifier. Javier describes the device as a big machine with an arm attached and says the magnifier was a far cry from the iPad she uses now.

One of the most well-known inventions for the visually impaired is called braille, a method of language in which words are represented by formations of small bumps on embossed paper.

Daisy Soto, a Latin American Studies and Spanish major at SFSU, was born visually impaired and could no longer see print by the age of nine. This did not stop her from reading.

“I was actually very lucky in that I had a teacher for the visually impaired when I was four or five,” Soto said. “She taught me braille and print in tandem.”

Regardless of the technology they use, most students with visual impairments find it necessary to start communicating and coordinating with their professors months in advance in order to ensure that the course materials will be accessible on the first day.

Associate Vice President for Student Affairs Gene Chelberg, who has been blind since he was 14 said, “the biggest challenge for blind students is getting access to course materials.”

Chelberg says this process has gotten easier over the years and now visually impaired students can use just about any computer on campus.

Through the purchase of a server-based license, which is an arrangement that allows schools and organizations to buy accessible software for all their devices at a discounted price, SFSU has taken an important step toward fully integrating disabled students into the traditional classroom setting.

“We’re moving away from that special ed approach,” Chelberg said. “You know, where disabled students are all by themselves, to a more universal design and integrated approach where folks can use any machine.”

These improvements in the campus library caused some people in the administration to consider closing the Accessible Technology Commons altogether, but this proposition was met with contention due to the nature of methods that blind people use to work.

“It’s kind of strange to work in an environment where there’s just a bunch of computers next to you.You’re working with someone and talking, and you’re generally supposed to be quiet in the library right?” Vang said. “We live in a world where blindness is the exception, so I go in with the mindset that I will probably have to explain that to every single professor I interact with. But I think that it’s important for the campus to have trainings on how to make documents accessible and what things to take into consideration