Written by Mette Mayli Albaek

They weigh nothing and take up no space in your bedroom. Americans seem to love them, which may explain why the sale of e-books increases every year several hundred percent. In fact, today one-tenth of all books bought here are e-books and in 2010, Americans spent 441.3 million dollars downloading them from a computer screen. But even when the sales of e-books in only one year have risen by 164.6 percent, the old-fashioned book will not die. And if they won’t die on their own, why do we not just kill off these dusty, old-fashioned, predecessors? Because each of these relics tells a story of its own?

Each, indeed, does that.

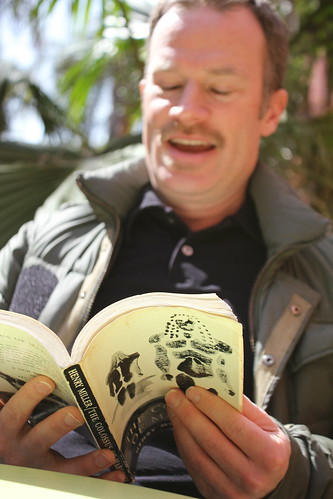

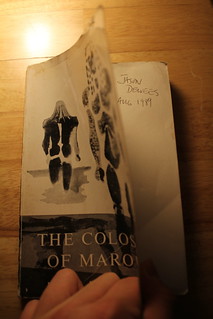

Whoever bought this copy of The Colossus of Maroussi in 1989 for six dollars and ninety five cents must have read it several times and brought it to difference places—at least that is what the no-longer-white cover seems to proclaim. Other telltale clues indicate that the prior owner liked coffee while reading and did not worry a page or two getting dog-eared or torn. But then something happened: Could he no longer stand the thought of the 244 page travelogue written by the famous American-German author, Henry Miller? Or maybe he died—might his children brought in all of his books for an estate sale?

However it got there, right now that very copy of The Colossus Of Maroussi is just one of twelve hundred used books on the bookshelf in the lending library Ourshelves at 998 Valencia Street in The Mission. On page two, the name “Jason Dewees” is written in capital letters that slant to the right on two separate lines tilting down a little.

The e-book simply does not provide the same opportunities for such personal interaction, says Maxine Chernoff, professor and Chair of Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. “You can write your own notes in a printed book. You can highlight whatever you want. A book becomes a personal object in that way, and you cannot get the same individual feeling by downloading something on the Internet.”

She reaches out for one of the many books in the bookshelf at her office.

As she turns through the pages she points out how leftovers and curly pages usually characterize her books. Chernoff has published six volumes of fiction, eleven of poetry, and in summer 2011 had her first e-book published. She admits to feel nostalgic about printed books and that is also why she does not think that e-books will ever kill off traditional books.

“The technological development is a great supplement,” she concludes, “but I simply do not believe that e-books can ever replace the importance of the physical feeling of having a book between your hands.

So who is—or was—this Jason Dewees and what is the real story about this print copy of The Colossus Of Maroussi? This copy of the nineteenth edition with his name in it may be in San Francisco, but of course that does not necessarily means that the old owner of this paperback book was also from here or even still lives here.

Using primitive Internet research methods such as White Pages and Facebook reveals 36 people named Jason Dewees in California. Narrow the search to San Francisco, and there are two men with that name. One of them likes to play video games, and is a fan of the Philidelphia Eagles according to the “about” button on his Facebook page. But this Jason Dewees is only 35 years old, meaning he must have been only 12 years old in 1989 when someone autographed page two of this copy. That sounds too young an age to read Henry Miller.

A Google search shows an article from 2009 where Jason Dewees from San Francisco is mentioned as the big palm expert. Another search shows that this palm expect is also freelance writer at a magazine called Garden Design. This clue may not be a dead-end.

In fall 2011 Amazon said it is now selling more e-books than paper ones and downloading college textbooks has also become more popular. This development also influences student opportunities to borrow books at SF State.

Among the three million items in the libraries of the university, there are now twenty thousand e-books available, so the electronic words are still only a fraction among the material at the libraries, but they already have a place on campus. More significant is the fact that in the last three years, twenty-five percent of all new additions are e-books.

Besides being a big fan of the printed book, David Steele Hellman is responsible for adding new titles to the university libraries. He asserts that there is no official policy about how many e-books the libraries can buy. Such decisions are made on a title-by-title basis, and right now the e-books at SFSU libraries are mostly how-to manuals or technical books.

“Everyone in the book industry is trying to figure out what is a good to have on e-books, Hellman explains. “We can see that our e-books actually are getting used by the students.”

He is concerned thought that he is also nervous about the development because not everyone has what it takes to use the e-books. A survey from last year tells that fifteen percent of the students at SFSU do not have a computer—a real reason to be worried.

“In the future you will have a problem if you do not own a Kindle,” he continues. “I fear that—especially in the public libraries—you will not have the same opportunities to walk around finding books and take them with you.”

For ninety-nine cents, you can go on peoplesmart.com and buy the phone numbers of both Jason Dewees in San Francisco. Of one them is living in Richmond just across Golden Gate Park. Apparently this one is born in 1968. Would he have read Henry Miller at the age of nineteen? The phone number linked to his name rings seven times, before a man says hello without identifying himself. “There is no Jason here,” he says. He pauses a moment, and then reveals that his son Jason moved away many years ago.

On hearing about the book hunt for the owner of The Colossus Of Maroussi, the man chuckles: “It was that kind of books Jason read in college. But let me give you his phone number; he still lives in town.”

If the son of this man is the right old owner of the book, it seems as though it will be all too easy to unravel twenty-two years of personal history. And so it is.

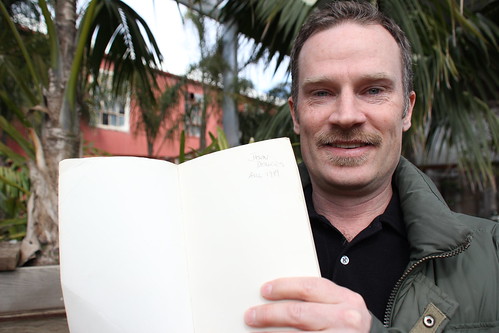

Between thousands of exotic plants, he stands at his job in the Flora Grubb Gardens in the southeast part of San Francisco, remembering being nineteen and returning from a summer vacation, when he put the The Colossus Of Maroussi back on his bookshelf.

After graduating, a lot of his stuff was stored at his parent’s house until a house fire water-damaged a lot of books in the basement a year ago.

His father reconstructed the basement into a garage and then donated some of the books—this volume being one of them.

Fortunately, the reality proves that the front of a book does not tell everything as becomes clear as Jason continues his story. He bought his copy of The Colossus Of Maroussi at a seventy percent discount, and he read it only once. Moreover, what looks like dried coffee inthe corners has nothing to do with coffee.

“I bought the book in the end of the summer 1989,” Dewess recalls, “because I needed something to read while travelling around in New England and Boston. At that time I was working in City Lights Bookstore, and I think a colleague of mine suggested I read Henry Miller.”

Dewees takes the book and starts turning through the pages. “I remember that I thought it would be fun to read a travelogue during my own travel and that was the only time I read it,” he continues. “Even though I am not at all afraid of eating and drinking coffee while reading, I think the marks on the cover are from the water damage and not coffee. I love that a piece of my history is still living, because I wrote my name so many years ago. It is very primitive but personal attachment to the object. I would say that it is an emotional experience of my live just coming up because I am starting to remember what I did that summer and why I bought the book.”

mazzymookameyer • Dec 13, 2012 at 11:55 pm

I want to read that Colossus of Maroussi book.