Service Dogs 101: Intro to the good boys and girls of the Bay Area

Daisy Soto cuddles her service dog, Miles in San Francisco, Calif. Feb. 26, 2020. (Emily Curiel / Xpress Magazine)

The first time Billie, a sensory processing service dog, saved the life of Cloud Galanes-Rosenbaum, 33, was during the 2015 San Francisco Pride Parade. Galanes-Rosenbaum, a Castro District native who has Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), experiences severe panic attacks when she experiences too much sensory input — blaring music accompanied with hundreds of bellowing voices can trigger attacks.

She said that during these moments, she goes into a “fight or flight” response, a survival mechanism that enables people to act quickly during perceived life-threatening situations, causing her to become unaware of obstacles and people around her. Because of this, Billie is trained to bring her owner back to reality.

One of the [Pride] floats was driving by and I didn’t see it. I was just panicking, trying to get out of there,” Galanes-Rosenbaum said. “And [Billie] walked right in front of me and stopped and just locked up. So, it was [either] trip over the dog or come back to reality.”

Galanes-Rosenbaum said she walked directly into her carob-colored Australian Kelpie, clearing the haze of her panic enough for her to walk into a corner and remove herself from the crowd. Billie successfully analyzed the situation, sensed her owner was in danger and acted.

The tactic of going against her owners will — walking in front of a moving obstacle — is called intelligent disobedience; a life-saving skill taught to service dogs like Billie.

“I did break down and ugly cry like a crazy teenager,” Galnes-Rosenbaum said. “But it’s better than dying … and it’s just — oh God, it tears me up when I think about it. She’s saved my life so many times.”

Service dog partnerships could be seen as symbiotic with how they communicate without words. There is an unspoken agreement of trust between a handler and their dog that is tested every day by the world around them. Though the relationship is critical — a service dog’s utmost priority is its handlers safety. The bond between the two embodies nothing but unwavering devotion.

“She’s opened me up,” Galanes-Rosenbaum said. “She’s taught me a lot about interacting with people [and] that I don’t have to be scared of everyone.”

According to the American’s with Disabilities Act (ADA), a service dog is a working animal — not a pet — that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities. There is a vast spectrum of service dogs trained for several disabilities and conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder and visual impairment.

In contrast to service dogs, therapy and emotional-support animals aren’t covered under the ADA because they don’t perform a special task for a handler. Galanes-Rosenbaum, who personally trained Billie and is currently studying to make service dog training a profession, broke down the three categories.

“In California, and most reasonable states … a service dog is a specific dog, with a specific task, for a specific disability and a specific person. If you can’t meet all of them, they’re not a service dog,” Galanes-Rosenbaum said.

Galanes-Rosenbaum said that a number of animals, from dogs to peacocks can be considered emotional-support animals. However, these animals are considered pets and aren’t allowed in public spaces.

In California, emotional-support animals are covered under the Fair Housing Act — a law established in 1968 to put an end to housing discrimination based on race, sex, religion, etc. This means people with mental and emotional disabilities can legally live with their emotional-support animal in no pet policy homes.

“Legally, all you have to do is get a letter from your doctor that says, ‘yes this is an assistance animal,’ register them as an [emotional-support animal] and present it to your landlord,” Galanes-Rosenbaum said. “They’ll let you in.”

Therapy animals are actually the opposite of these two categories since these cuddly creatures provide comfort to others instead of their handler. Therapy dogs — and local celebrity cat Duke Ellington — can be spotted on the SF State campus surrendering to belly rubs from eager students.

“[Therapy animals] don’t need to know how to ignore pets. They don’t need to know how to sit quietly under a table because they’re there for someone else,” Galanes-Rosenbaum said. “If you have a crazy poodle that just goes up to everyone and wants to lick them, that dog could be a therapy dog.”

West, a posh poodle who sits and poses when he thinks you’re taking his picture, only becomes a lively pup as soon as his “Service Dog” vest is removed. SF State Clinical Mental Health Counseling graduate student Anna Goose, 26, received West in August 2015 as an alert dog for her narcolepsy — a chronic sleep disorder that consists of overwhelming daytime drowsiness and sudden attacks of sleep.

Goose, originally from Cincinnati, Ohio, met her coily-haired companion at Pawsibilities Unleashed — a non-profit in Frankfurt, Kentucky dedicated to providing service dogs and service dog training to persons with disabilities. West is the first dog Goose has ever owned.

“My disability does not happen all the time,” Goose said, referring to the sleep attacks. “I call it ‘episodes,’ some people call it ‘flare ups.’ But the short version is, [West] can tell me before it’s going to happen.”

As for the long version, Goose trained West to pick-up scent changes in her hormones using frozen samples of her saliva labeled with the date, time and severity of a sleep episode.

Liz Norris from Pawsibilities Unleashed said some dogs naturally pay attention to a change in body scent and become keenly aware of it. If that dog were to become an alert dog, it would need to first be taught an “alert” signal — a consistent physical signal that the dog gives every time it smells a change in scent. For Goose, this signal is a firm nose nudge to her leg from West.

“Whenever I was having an episode, I would take one of those round cotton swabs and stick it inside my cheek so it would absorb the saliva,” Goose said. “Because whenever … whatever hormones are flowing in your body, those hormones are also in your saliva. … At first you just have [the dog] smell [the cotton round] and then you have them smell it and do a specific alert signal. And then you have them smell it and wait for them to do the alert by themselves.”

Goose is quick to mention that during all of this training, West is constantly being rewarded with treats and a swift “good boy!” The goal for West is to have him be able to do the alert on his own 85 to 90% of the time. These days, he can pick up her change in scent and alert her five to seven minutes before an episode is about to occur. The purpose of these early alerts is to give Goose enough time to take her medication, a stimulant to help her stay awake and get to a safe spot.

As with any visible variance, Goose’s life with West has drawn a spotlight on the two that hasn’t always been the brightest. Because Goose’s disability, like many, is invisible to the public eye, she sometimes encounters uninformed comments from community members.

“Sometimes the biggest challenges we face are the ones that other people can’t see,” Goose said, after a long pause and a few quick glances to West. “And when it is a disability that other people can’t see, in the body of the person [who] is disabled, it’s magnified a thousand times because of the assumption by everyone else that they’re OK when they’re not.”

Goose sometimes debates whether having a service dog is a blessing or a curse with this new-found attention that isn’t always friendly. Goose said one time a man sneered at her on San Francisco Muni when he didn’t believe West was a service dog.

Life with West has brought her cuddles and a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

“Not always on time,” Goose said with a grin. “But like, I have to get out of bed at some point because I’ve got someone else to take care of. It’s not just about me anymore. There’s another creature that needs attention and love and needs to be cared for.”

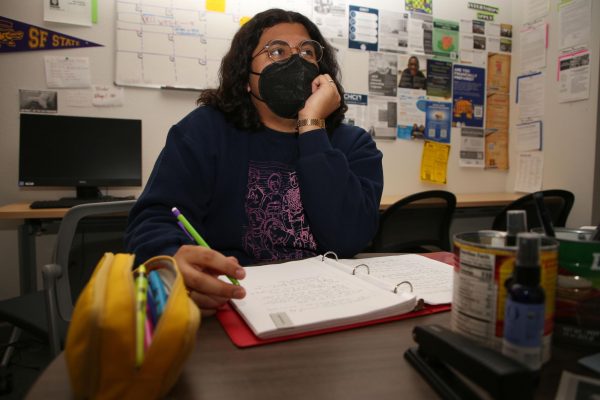

Daisy Soto, a 27-year-old San Francisco State student who has Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) — a degenerative eye disease — received her service dog Miles from Guide Dogs for the Blind (GDB) in 2016. Soto sweetly calls Miles her “Holiday Dog” because he was born on April Fools’ Day and she got him on Halloween. Although the two exude nothing but confidence when they stride to class, Soto was initially apprehensive about having a guide dog because she got so comfortable with using a cane.

“At first I was kind of like, ‘I don’t know how much a guide dog would really improve my form of travel,’” Soto said. “I knew that it would allow me to walk faster, but beyond that I was like ‘I don’t know how much I’d be able to trust a dog. How much it would really help out in terms of my mobility.’ But I was very intrigued, so eventually I ended up applying for [a dog].”

Soto’s doubts were reasonable considering a guide dog’s purpose is to lead their handler to a destination safely and undistracted. But Soto said it comes naturally to the two. And because guide dogs are so thoroughly trained — they go through a year’s worth of training with a volunteer handler before enduring intense guidance and safety tests with professional trainers. Soto said she assumes Miles just knows what he’s doing.

“He was so good from the beginning,” Soto said. “Obviously [guide dogs] make little mistakes. They’ll run a curb or brush you against a person, little things like that. I guess he’s never given me a reason not to trust him. With him, it comes instinctively.”

Soto’s trust in Miles was tested a month after they left the GDB training facility. During a rainy night at a traffic-heavy roundabout, Soto almost crossed in front of a car she didn’t hear. Miles took the initiative to pull Soto backward away from the car.

“I call him ‘my best little bud’ [because] he’s always there when I’m sad or stressed. He always seems to know,” Soto said.

One of the many things Soto’s learned from Miles is patience. She said the big thing with her and Miles — because she’s kind of a control freak — is giving him the chance to be successful and take control.

“He’s taught me to relax and trust him a lot more. My friends kind of say [Miles and I] have little couple arguments where I insistently try and tell him to go one way and he ignores me and sits down. And then eventually we go his way, and he’s right and it’s really frustrating,” Soto said, chuckling.

![[From left to right] Joseph Escobedo, Mariana Del Toro, Oliver Elias Tinoco and Rogelio Cruz, Latinx Queer Club officers, introduce themselves to members in the meeting room on the second floor of the Cesar Chavez Student Center.](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/mag_theirown_DH_014-600x400.jpg)