A world where daughters of immigrants are forging paths into STEM despite cultural heritage and societal expectations is coming into reality. In a male-dominated and undiversified program such as STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), certain communities find it hard to feel like they belong to the program. According to Pew Research Center, Hispanics make up 17% of the total workforce in the U.S., but only 8% of Hispanics are in the STEM fields. [8] Latinas in STEM are breaking barriers at SF State, providing resources and representation to the field.

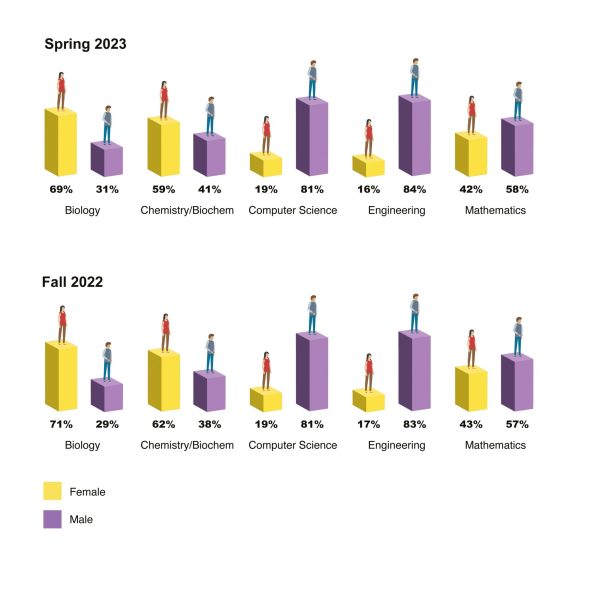

In Fall 2022, 5,457 students were enrolled and 2,159 of those students were women. In Spring 2023, 5,087 students were enrolled and 1,958 of those students were women.

Latinas in STEM (LSTEM) is an organization on campus which was founded to provide empowerment and a safe space for Latinas to thrive. They help find resources that many Latinx students struggle to find, as they do not have the same access to STEM starting out.

Amayrani Villegas, alumna of SF State and founder of LSTEM, described her experience where being a woman in STEM created a great work ethic, but also a hardship when it came to family. Villegas talks about a cultural dependence to help her family and had to discover how to find a balance.

“We come from a culture where we work hard. It’s in our blood to work hard for what we want. At the time I was about 19-20, I had up to five jobs at one point to support my family,” said Villegas. “I had to really make sure I can provide and support for myself, but also not put a burden on my family financially. I think that was the first hurdle being a Latina in STEM.” She remains passionate about Latinas being an asset to STEM and creating a shift in the industry. When a doctor can speak Spanish, there is a level of trust that comes with that and that already creates a change in the community.

Villegas believes coming from a diverse background means they have a different way of thinking that others may not have.

“The main reason why I started [LSTEM] was [because] I wanted to increase diversity in STEM,” Villegas said.

Villegas saw the change in Latina students once they started attending LSTEM from not knowing what they were doing to receiving fellowships in their field. She spearheaded resume workshops and how to apply for scholarships. She believes if LSTEM continues, SF State can be recognized for the highest diversity in STEM by having more Latinas.

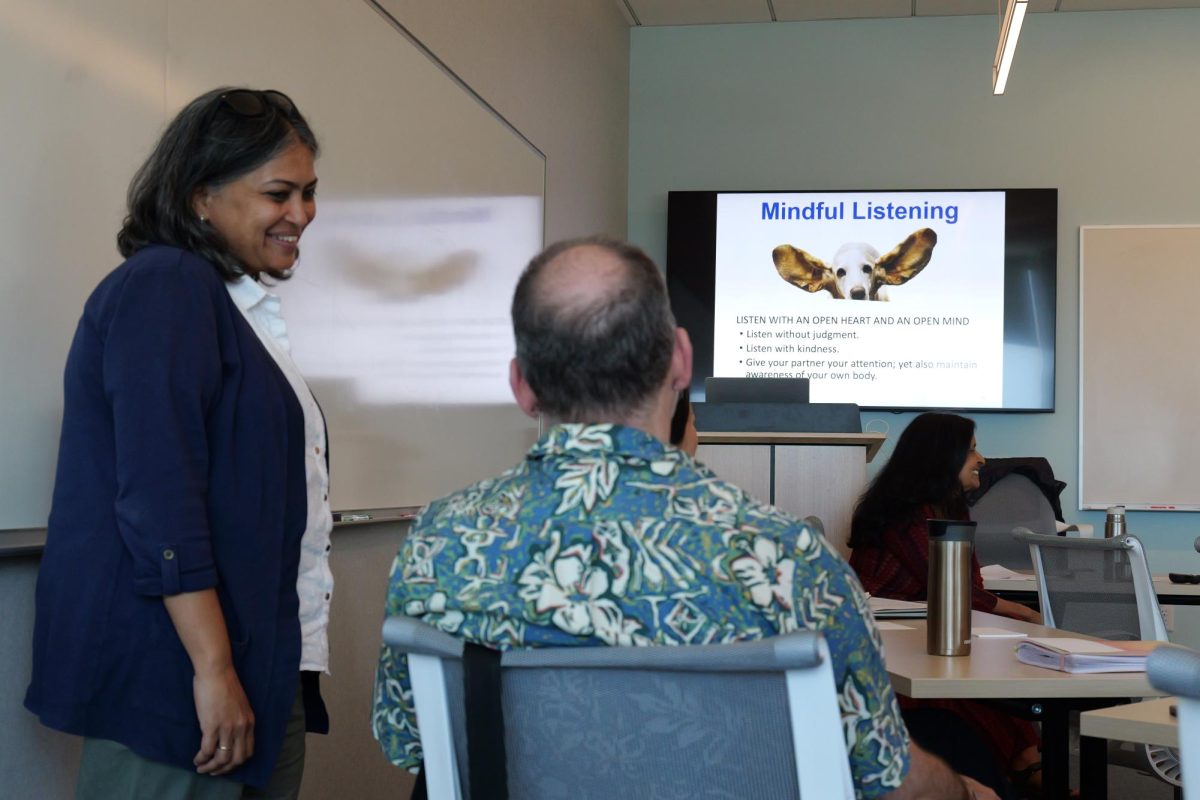

Carmen Domingo, dean of the College of Science and Engineering, discusses how she plans to keep diversifying the program within faculty to show students there is progress to be made about representation in the classrooms.

“The path to becoming a faculty member is long so you have to have a lot of persistence and you have to really overcome things like stereotype threat where the environment is conveying a signal or — maybe you don’t fit in or be good enough,” said Domingo. “I think [SF State has] got to work really hard to hire faculty so that the students see themselves in it.”

As a Latina in power, Domingo reflected that when she was a young student she did not feel as prepared as other students for college coming from an intercity school. She explained how not having a supportive classroom environment makes a difference.

“Students are asking for [more representation] and I want to deliver. We’re also working hard in thinking about the curriculum that we offer and more importantly we teach it, how do we create these welcoming spaces,” said Domingo. “We have a new assistant dean who’s really gonna help with launching anti-racism efforts and looking at how do we create these spaces that our Black and Brown students feel included and represented in the work and discipline.”

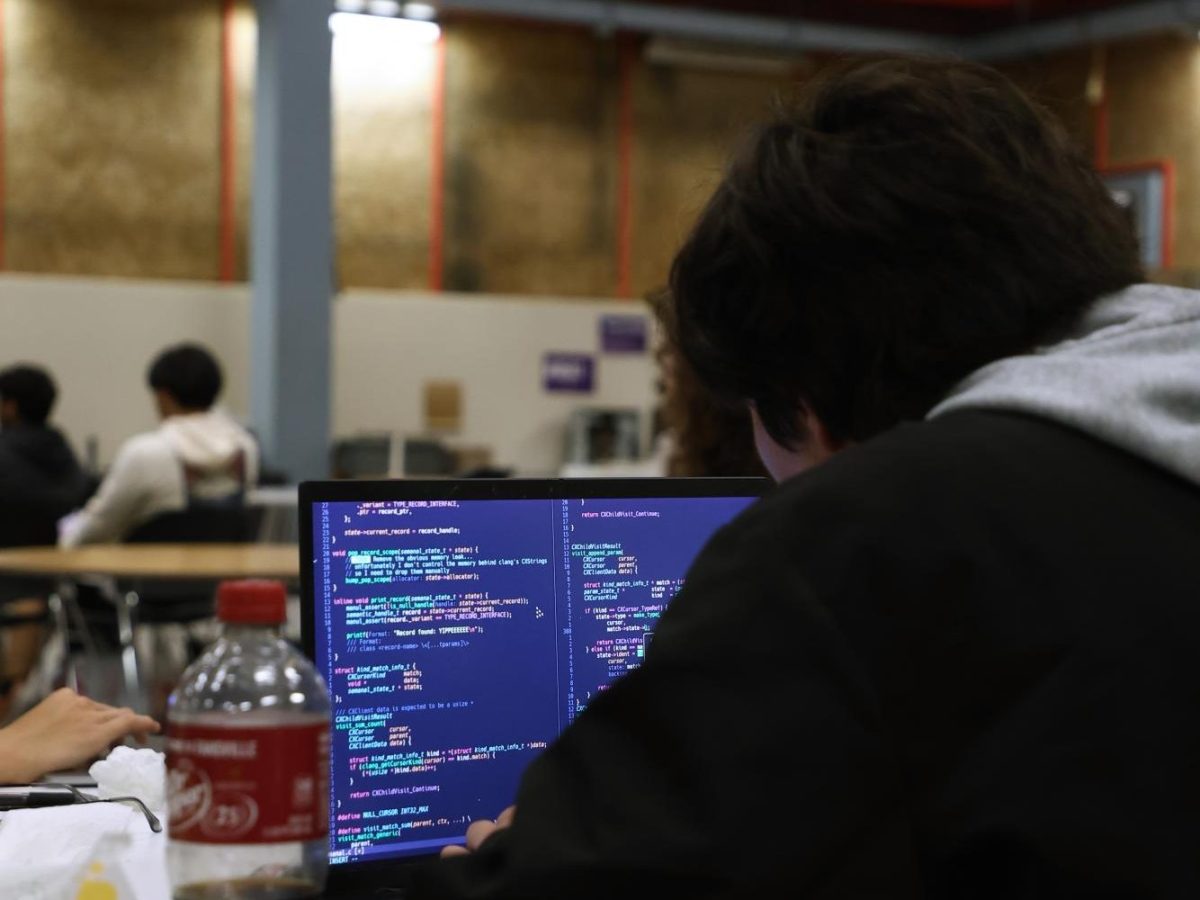

Viclarie Lozoya, a first-generation Latina and eldest daughter, discussed how she struggled with knowing exactly what to do in order to get on the STEM path.

“For me it was really difficult because everyone is looking up to me and assuming I have all the answers, but thankfully we have technology, and Google was my best friend back in high school,” said Lozoya. “So I always thought this is what I have to do. I never saw all the nontraditional paths like — hey, you can go to community college and still end up at UCLA after.”

As the eldest daughter, she was cut out from her family for wanting to move out, focus on her career and go to college. Lozoya said many Latinas struggle with feeling guilty for not being able to stay with their families. Lozoya discusses how she wants to rebuild her community by bringing back resources to them and revealing different routes that can help Latinx students. She wants to break the stereotype surrounding Latinx women of settling down early because she believes women are more than that and should be free of not having to comply with one narrative.

Perla Gómez Olguín, a third-year biology major with a concentration in physiology, felt lucky to receive help from her high school counselor, Mr. Escobar, who guided her to the path she needed. Olguín’s father was diagnosed with cancer, and claims doctors failed to give him adequate care because of their ethnicity so she decided to become a doctor.

“I just think that if there was more representation in medicine or just in general in STEM that there could’ve been a better way to treat patients like [my father],” said Olguín. “That English isn’t their first language or that they struggle to explain themselves […] if there was someone that had similar backgrounds or stories they’re able to understand them better.”

In California, Latinx comprised 39% of the state’s population, yet just 6% of physicians were Latinx and 3% were Latina. Olguín talked about bridging the gap for those who need a person who understands their culture or language in healthcare.

“Just having that [diversity at SF State] made me realize […] having good Latina representation really matters and it does impact the way you do in school and how you want to leave an impact in the future,” said Olguín. “It motivates me more to do better in school and I know that I can do it knowing there are so many other Latinas that are just as excited and motivated.”

![[Video] No Trump, No Feds, No MAGA; San Francisco says "No Kings!"](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-28-165913-1200x675.png)

![[Video] Gators Give Heartfelt Donations to Blood Drive](https://xpressmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/bloodstill2-1-1200x675.png)