Researchers, students, artists, politicians and tribal communities gathered together on boats to conduct scientific research involving the development of wind farms offshore Morro Bay.

As they approached the area, a variety of marine animals such as whales, seals and even birds flying in the sky could be seen within this area. As the future approaches, so will wind farms.

Clusters of floating platforms about 20 miles off the shore of Morro Bay will carry wind turbines. Each wind turbine is 900 feet tall, making it taller than the Golden Gate Bridge. Collectively, these wind turbines create what researchers call ocean wind farms. These ocean wind farms are powered by offshore wind produced by our oceans, making the energy captured by these structures natural and renewable.

According to CalMatters, ocean wind farms are essential to electrify California’s grid with one-hundred percent clean energy.

“The development of this offshore wind could be an important part to increasing our renewable energy portfolio including offshore wind,” Simonis said. “It could get us closer to 100% carbon-free energy and reduce the types of pollution that are associated with fossil fuel extraction.”

Last December, the federal government auctioned off 583 square miles of ocean waters off Humboldt Bay and Morro Bay to build five wind farms. Among the researchers working on the production of this project is SF State’s Estuary and Ocean Science Center’s Anne Simonis.

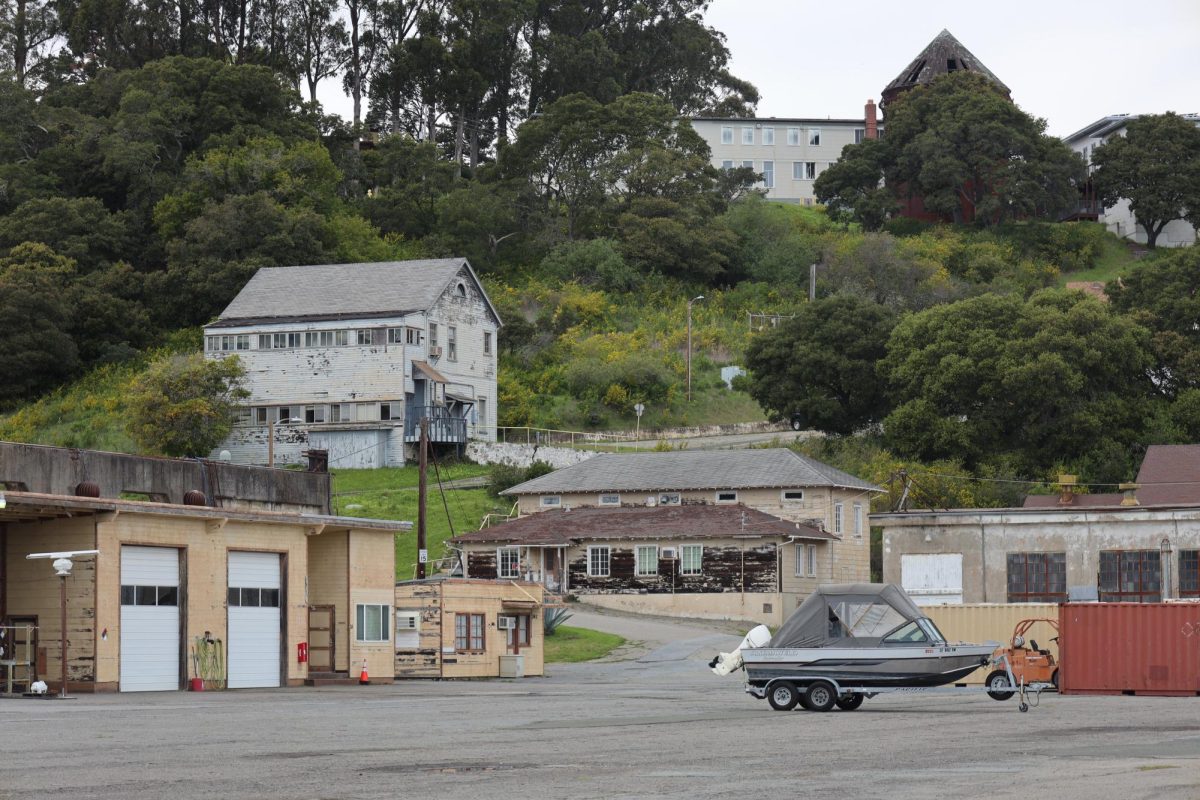

Simonis is an acoustic ecologist, oceanographer and adjunct professor of biology at SF State. She works as a research affiliate with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service as part of the ADRIFT program, which studies ocean noise and marine ecosystems in the wind energy area. Morro Bay is located on the central coast of California, over three hours away from SF State. This research is funded by the Bureau of Offshore Energy Management.

Each wind turbine offshore Morro Bay will be anchored to the ocean floor about a mile apart from one another. Ocean winds will blow into the turbines where the energy will be captured. The stronger the winds, the more power is generated within the turbines. The turbines generate electricity using aerodynamic force when the wind and rotor blades collide, spinning a rotor connected to a generator. Undersea cables will transport the energy to either onshore substations or floating substations before being sent to the state’s grid.

Each wind turbine is connected to a structure called a floater with one segment holding up the turbine and others balancing the weight to buoy the turbine. Cables and mooring lines connect each segment of the floater to an anchor buried in the ocean floor. Each line can range to 3,000 feet long.

As the science behind wind farms is fairly new, companies are expected to spend up to five years preparing technical plans and analyzing the potential environmental impacts of each project before the construction of any regularly operating wind farms.

At Morro Bay, Simonis conducts research focusing mainly on analyzing the area where the wind farms will be built and finding out which marine animals will be affected through environmental analysis. Simonis can determine this through sound, scientifically known as acoustic data.

According to Simonis, the construction of these wind farms will have fewer environmental impacts because there will be less underwater noise pollution.

“The installation of turbines are going to be much quieter than the turbines that are connected to the seafloor,” Simonis said. “They usually use these giant pile drivers, which are incredibly loud and are known to disrupt or displace many marine mammals from the area they usually reside and they end up leaving the area for a while.”

Simonis captures sound through buoys. Each buoy collects underwater sound as it drifts within the area. Through sound, Simonis can determine what kinds of marine animals are living or passing through areas that have the potential to be affected by the construction of wind farms.

In her research in Morro Bay, Simonis deployed eight drifting buoys into the ocean water within the wind energy area. From here, the buoys drift within the ocean currents for days or weeks at a time, capturing sounds. These recordings are collected seasonally and during different times of the year in order to collect a wider scope and detection of what marine animals are present as well as what they’re doing there. Important factors such as what places they ventured, their movement and their behavior can all be interpreted within these recordings.

“I am collecting acoustic recordings in the ocean and right now, the main way that I collect those acoustic recordings is through drifting buoys,” Simonis said. “And we have to go out and recover those buoys to get our data back.”

Because of the height of each turbine, birds have the potential to fly through the wind energy fields produced by the wind farms.

Tammy Russell is a seabird ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego working on this project. According to Russell, this area within Morro Bay is an important area for seabirds as they come here to feed.

“Sea birds are kind of the only marine animals that we can see easily because they spend most of their time flying around or sitting on the surface of the water,” Russell said. “But they’re telling us a lot about what’s going on underneath the water and things in the California current.”

Each of the wind farms will require an extensive network of offshore and onshore development, such as miles of undersea transmission lines, expanded ports, new or upgraded onshore substations and electrical distribution networks.

Although they will be able to provide power to approximately 1.5 million homes, researchers such as Simonis are concerned with how construction could impact the Morro Bay community.

“These offshore wind farms can be an incredibly important way to increase our renewable energy, but they also are likely going to have a big impact on the communities near which they’re installed and not everyone is excited about that,” Simonis said.

How wind farms will play a role in our future is currently unknown; however, Simonis finds excitement in being a part of its development.

“This is a really new technology so we aren’t really certain what the impacts will be,” Simonis said. “The amazing thing about how this project is rolling out is that we have this awesome opportunity to go out, study the area and establish what the baseline conditions are before the wind farms are actually installed and operational.”

This research is being used by Data Nuggets to educate those within our school systems about this research and prepare them for the future. Data Nuggets is a program which works directly with scientists and researchers to help them communicate their research to all grades within the education system ranging from elementary school to undergraduate students.

“We have a strong emphasis on data literacy,” says Data Nuggets cofounder Melissa Kjelvik. “We like to include all sorts of different tidbits about how the research went and it shows the messy side of data collection and analysis in research so that students have an opportunity to practice those skills and help them interpret the messy data that’s probably more similar to what they experienced in their own research as well.”