Enrollment is drastically decreasing across many California State Universities, including SF State. SF State has seen a reduction in enrollment over the past five years for full-time equivalents, a figure the university uses to measure enrollment numbers. There has been a 20% reduction this past year alone and this trend isn’t expected to slow down.

With the cost of living in the Bay Area, ramifications from COVID-19 and students dropping out at a higher rate, the big question is: how will SF State adjust to these diminishing numbers?

“For the last five years [CSU] enrollment has gone down for incoming students, […] especially first-time freshmen,” said Sutee Sujitparapitaya, the associate provost of Institutional Research at SF State.

President Lynn Mahoney explained in an interview that we must “embrace that we’re going to be smaller.”

Why are the enrollment numbers down?

There are a few reasons why SF State is seeing lower enrollment. One is that during the pandemic students moved back home to shelter in place. More often than not, when those restrictions were lifted students remained where they were. Two-thirds of California’s population lives in the bottom half of the state, contributing to the decreasing numbers at northern CSU schools. This has led to less attrition of student enrollment in some Southern California schools than Northern California schools.

Enrollment in community colleges has plummeted by 20%, according to Vikash Reddy, vice president of research at the Campaign for College Opportunity, a nonprofit focused on equity in higher education.

SF State isn’t alone in its declining enrollment; Mahoney explained that San Francisco City College and the San Francisco Unified School District have also been experiencing a decline in enrollment. SFUSD is down 10,000 students since 2015, and City College is down about 59%. These schools are some of the largest feeders to SF State and have maintained the health of the university’s enrollment for years.

Community college populations are vastly important to the CSU system, making this a state-wide problem.

Another important factor in the decline of student populations is the cost of living in the Bay Area. The high costs of rent, groceries and other necessities are punishing for students, which may influence the college decision for those outside of the Bay Area.

“There is little I can do about the cost of living in San Francisco,” said Mahoney.

The Bay Area job market is also a factor. According to Reddy, some students are dropping out to find high-paying jobs and putting their degrees on hold, which, in some cases, means never getting the opportunity to come back and finish. This allows them the time to make money to live here while gaining security with health insurance and higher salaries. Reddy points out that while this is a decent short-term solution, the long-term effects of salary ceilings and lack of advancement are often overlooked.

How will Mahoney pivot?

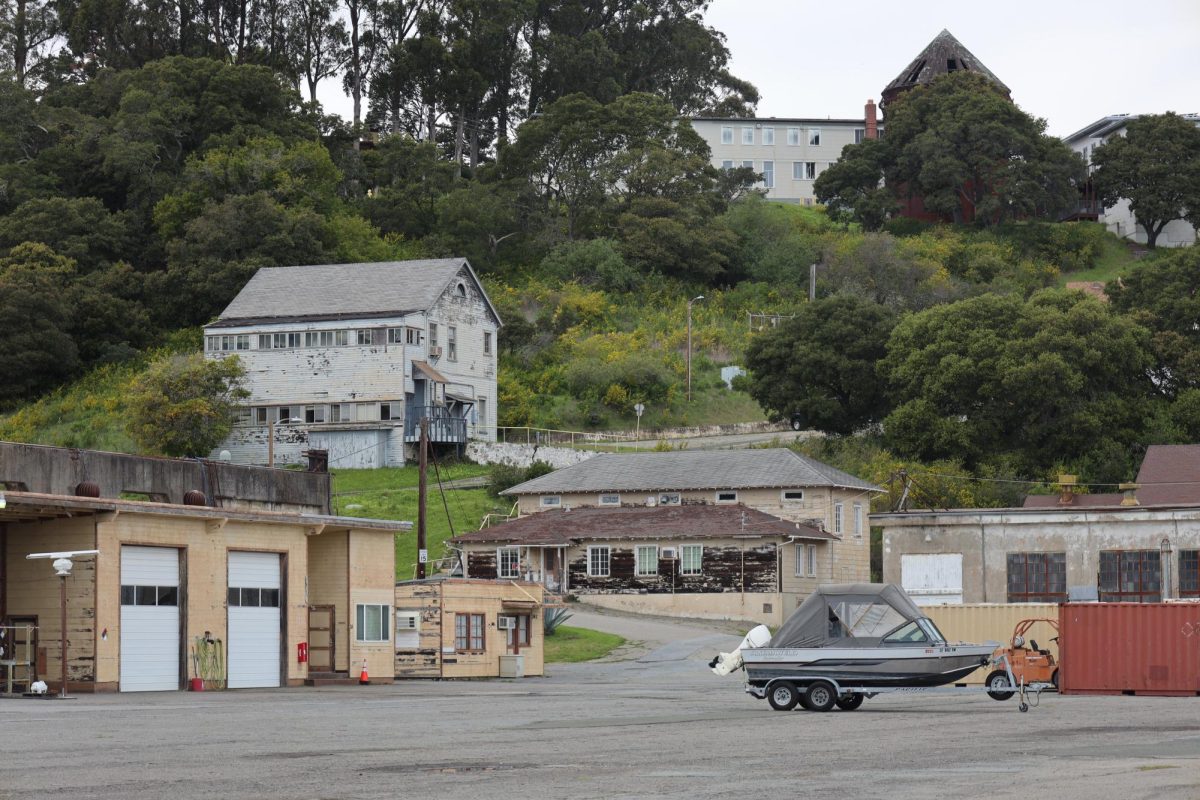

Housing

In response to the housing issue, the school plans to open a new residence hall next fall. The state has subsidized about 75% of the building costs, which helps the university’s financial burden. The savings allow the university to pass on savings to students through the Reduced-Rate Student Housing Program. The program, which will start next fall, will give first-year students a 25% discount on student housing across campus residencies.

She is also looking into new ways to help students who live off campus. Mahoney is looking to generate philanthropic dollars from corporate and private sponsors that would help students with the cost of rent in the area.

Classes and Faculty Reduction

When asked how she plans to go from a 20,000+ student institution to a smaller one, Mahoney offered a few answers, including a smaller class schedule and severance payments to faculty.

“It’s actually shrinking our scheduled classes to match the number of students we have,” said Mahoney. “That’s not easy.”

She explained that these aren’t the budget cuts that students complained about this past spring semester, instead, it’s adjusting to the new number of students. The administration does predictive analysis of enrollment semester after semester, which aids in making decisions to create a smaller schedule before registration.

“First and foremost, [course numbers are] shrinking because it’s aligning the class schedule with the students,” said Mahoney. “That’s easy for me to say, but it’s hard to do.”

Mahoney recognizes that with change comes pain. SF State has had to lay off faculty as a result of these changes. The administration could not provide specific numbers on these layoffs.

“I am mindful every time I talk about this that there are human beings whose lives are being affected,” said Mahoney. “But, at the end of the day, I have a fiduciary responsibility and you can’t spend money you don’t have.”

The effort to condense the schedule is a process that involves the administration and the head of each department. It starts with each department building a schedule followed by administration matching that schedule with student numbers and the budget. Negotiations go on from there.

As part of the efforts to reduce the campus’s budget deficit, the administration is offering the Voluntary Separation Incentive Program, which allows faculty to resign with severance by June 30, 2024. The severance equates to 50% of the employee’s annual salary up to $75,000. Faculty who want to take this offer have to be eligible for retirement and have at least 10 years of service at SF State.

“We have set aside a certain amount of money,” said Mahoney.

The future looks smaller for SF State but Mahoney thinks things can also be better.

“There’s no reason we can’t become smaller and better,” said Mahoney. “Our mission is really clear. For the most part, it is to service undergraduates and give them a transformative experience that leads to upward mobility.”