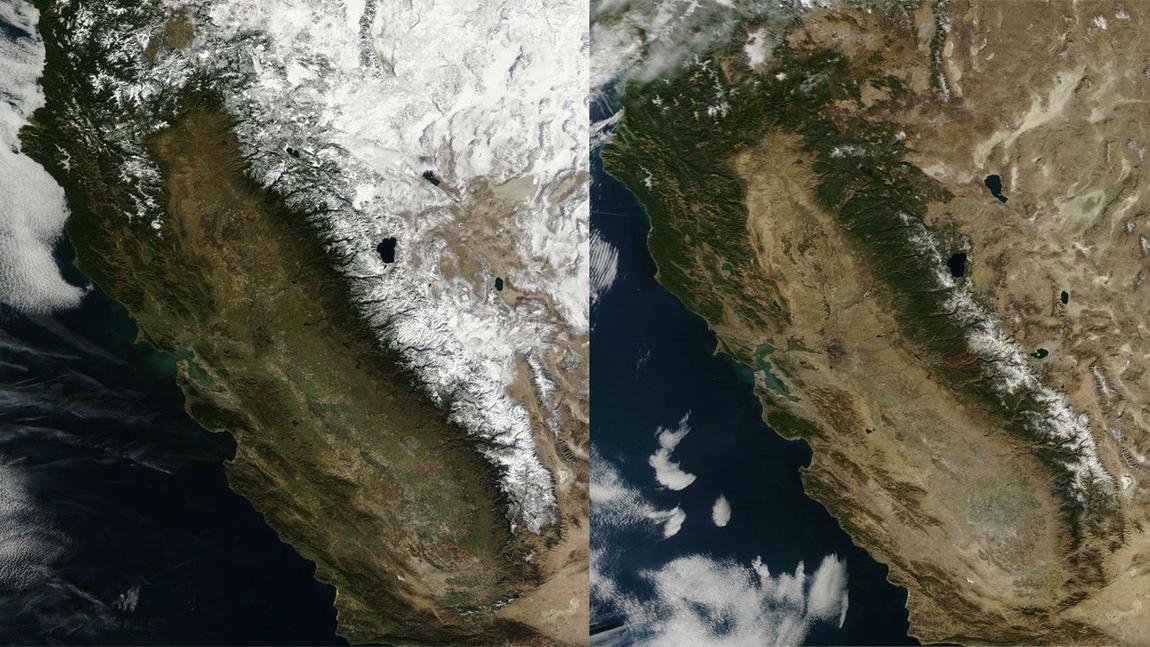

Featured Image: NASA comparison between California in 2013 (left) and 2014 (right).

There are 38.8 million people in the state of California. Collectively, they use four trillion gallons of water for domestic and municipal purposes annually. However, that amount accounts for only 20 percent of water allocation in the state; the remaining 80 percent is used by big agriculture.

This information, from the California Department of Food and Agriculture, is becoming the basis of conversation for many who question the impact of the recently enacted, drought-focused executive order from Gov. Jerry Brown.

On April first, for the first time in California’s history, the governor enacted a mandatory 25 percent water reduction for all cities and towns. This came after Gov. Brown attended an annual snow-pack-measuring convergence in the Sierra Mountains.

“Today we are standing on dry grass where there should be five feet of snow,” said Brown in a statement to attending media. “This historic drought demands unprecedented action.”

“Therefore, I am issuing an executive order mandating substantial water reductions across our state,” said Brown in closing. “As Californians, we must pull together and save water in every way possible.”

However, the phrase, “in every way possible” does not actually mean in every way possible. Most of California’s 74,600 farms and ranches have been given full immunity from these cutbacks.

What’s more, Brown, and his administration, prevaricated requests for explanation on the exemptions by citing “hardship” and “previous, significant cutbacks” as reason enough to leave agriculture out of legislation.

Reality, however, differs on this account: As an industry, agriculture was valued at $46.4 billion in the also-drought-stricken year 2013, according to the CDFA. This represents a 15 percent increase in value; also, the most value ever generated by agriculture.

The 2014 numbers are not yet available.

Furthermore, “hardships” – what seems to be the euphemism for fallow fields – is strangely not accurate. There are currently 880,000 acres of fallow, or soon to be fallow, fields in California due to the drought, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. This represents 3.3 percent of California’s 27 million acres of cropland, a full double-digit percentage difference from cutbacks being asked of non-agriculture.

California also boasts 16 million acres of strictly grazing land, which is not in any drought calculations or legislation at all.

Voices attune to this balance-discrepancy, have not only been vocal on Gov. Brown’s lack of equal cuts, but the methods agriculture uses to stem the problems of the drought.

Mark Hertsgaard is a San Francisco-based environmental journalist and author of the book “Hot: Living Through the Next Fifty Years,” and recently spoke with Alternet, an enviro-news group.

“If you go down to the Central Valley, where most of the farming takes place, we are now in a kind of an agricultural arms race down there,” Hertsgaard said. “Farmers, neighboring farmers, everyone is trying to drill deeper and deeper wells to get down and grab that groundwater.”

According to the California Department of Water Resources, groundwater makes up 40 percent of agricultural irrigation water. However, due to a prolonged drought, that number may climb as high as 60 or 65 percent.

“The big danger of that, though, and this is the real, potential doomsday scenario here in California, is that the more you go down and use that groundwater and suck it up like a straw, the greater the danger is that you collapse those aquifers underground,” said Hertsgaard.

Collapsing an aquifer is serious and irreversible, according to the United States Geological Survey.

“The compaction of unconsolidated aquifer systems that can accompany excessive groundwater pumping is by far the single largest cause of subsidence,” a December 2000 USGS study, republished in 2013, found.

“The overdraft of such aquifer systems has resulted in permanent subsidence and related ground failures,” said the study.

NASA estimates that California would need 11 trillion gallons of rainwater to replenish the state from the drought. That equates to nearly 170 days of Niagra Falls’ water volume.

And with that, protracted drought conditions, desertification, economic hardship, and perhaps even diaspora are real possibilities, if 80 percent of California’s water usage is untouched by drought legislation.