A power switch is flipped on, revealing the low hum of a turntable, ready to play a carefully picked-out record. Once the record is placed on the platter of the turntable and the top of the turntable is closed, the tonearm clicks as it lifts and lowers onto the record. The record player’s stylus needle precisely lands at the start of the record, settling into the grooves with a loud thud. As the stylus needle spins around the record, cracking and popping from the dust and minor imperfections on the record echo from the speakers.

Anticipation builds in the brief moment of silence before the stylus needle reaches the start of the first track. A warm hum comes from the speakers before the music starts and gets louder and louder.

The turntable sits on the counter, spinning a record. The room is filled with the sound of smooth jazz making heads turn as they pass by the tucked-away record store. Records new and old are hung on the walls, are in carefully placed stacks and fill bookshelves around the small store. People stop by, recognize the nostalgia of the old records and reminisce on their favorite albums and artists while they flip through the many wooden crates of records.

In an era dominated by technology and the convenience that digital music apps such as Spotify give us, where music is easily streamed at our fingertips, one might expect the charm of physical music such as records, CDs and even cassettes to fade away. However, hidden among music enthusiasts and audiophiles, there is a resurgence of interest in physical music in younger generations. Record stores have continued to provide services and experiences that music streaming apps are unable to give their consumers — the comfort and nostalgia that only a vinyl record, CD or cassette tape can evoke.

The Recording Industry Association of America created a graph that shows the economic history of physical media. The graph shows that vinyl sales have been on the rise since 2006 and have increased again in 2018. In 2021, the total annual income revenue between vinyl, extended-play records and single-play records was more than $1 billion and is still going up today.

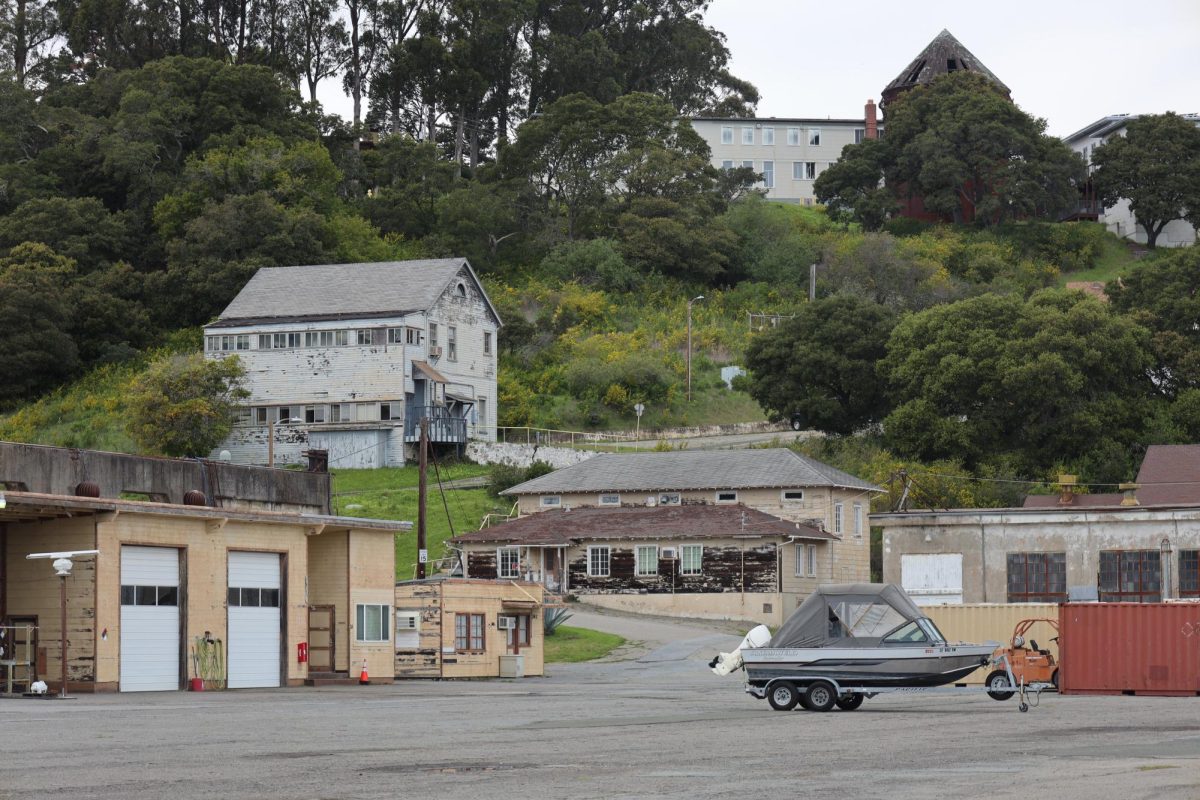

Ben Wintroud grew up around jazz with influences from his uncle and jazz producer Orrin Keepnews and decided to open Tunnel Records in 2017. Now with two locations — one on Taraval Street and another inside the historic 4 Star Theater on Clement Street — Tunnel Records is open to serve vinyl enthusiasts new and experienced seven days a week, intending to be the go-to music store.

Music is always changing but there has always been a need for record stores, even with the increase in the use of digital music. With years of knowledge about physical media and music in general, Wintroud can offer his consumers professional music recommendations and answer any questions someone might have about physical media.

“We [record stores] will always be kind of gatekeepers of information,” said Wintroud. “We will know what’s new and as we get to know our customers, we will have suggestions for them, and I think that will always be valid — kind of like going into a bookstore. If you tell the clerk at a bookstore your favorite author, they might be able to recommend something to you, and we can provide that service too.”

When a customer walks into a record store, they are greeted by the music that has been carefully selected by the employee working behind the counter. The atmosphere invites consumers to browse through the many stacks and crates of records. The customer can touch the music and find a deeper connection to the media they are surrounded by, which is something that digital music is unable to give a person.

“Listening to music digitally is really passive and I don’t think that people ever really get engrossed in what they are hearing, but when you actually have to start and stop something physically, I think it brings you closer to the actual media in itself,” said Wintroud.

Record stores bring a person in older generations back to when they were younger. Older generations started buying and sustaining record-buying habits, and they are the reason why there is still a desire among younger generations to consume records.

When a college or high school student walks into a record store, they see the now-vintage records displayed on the walls that a family member could have had when they were younger. They can now experience what it was like shopping for physical media, just like their family members did when they were their age.

“There has a lot to do with the tangibility of holding something like a record that has an actual weight to it,” said Chris Veltri, the owner of Groove Merchant Records on Haight Street. “You can feel the age on a record, the patina from all the people that have owned it before you. There is something about it that until you really get into collecting them you might take for granted and not actually realize.”

Shelby Ash has owned The Music Store in West Portal for 25 years. Ash opened his store from scratch, starting with just one rack of records and one rack of CDs. He has continued to share his love of music with San Francisco because he believes that San Francisco is a music town that enjoys having physical products.

Records store pure analog sound whereas digital music files are typically recorded, shrunken-down and digitally translated versions of analog sound. Some audiophiles argue that the sound being produced through digital platforms sounds different than the music being produced by records.

“When you shrink music down, like when you listen to a record and you shrink it down to a CD, you lose a little information,” Ash said. “But when you take the CD and you shrink it down to just streaming, you lose a lot of information, so songs don’t sound the same when you are listening online versus listening to it on a record — you lose a lot of sounds.’’

A lot of people won’t recognize the slight differences in sound, but to audiophiles, the pure sound that a record produces is very important.

Limited edition and rare types of vinyl can be added to a collector’s collection. With fun colored pressings and limited quantities, collectors are more driven to add different editions to their collections. Collectors can say that they have an edition that most other people don’t have.

“You can’t download a record,’’ Ash said. “You can download the music from a CD, but for record collectors, they want to have the actual record, the album cover, the artwork — they want the fact that they have to get up and flip the record.

Ash has noticed the recent increase in demand for CDs and vinyls from college and high school students who come into his store. This generation of college and high school students grew up being surrounded by digital media so having something physical was something they weren’t familiar with.

“My observation is that they [college and high school students] did not grow up with anything and their parents didn’t show them a CD,” Ash said. “They only had music online so they don’t have anything to identify with, and they are just getting into CDs and records because they didn’t have it as kids, and you have to have something.”

SF State students can take a quick trip on the M-line Muni to The Music Shop in West Portal and browse the CDs and records that Ash has to offer. They are transported back in time, allowing them to experience the classic record store ambiance and explore many different genres of music.

Alina Eckstein, a fourth-year music student at SF State, grew up around her parents’ large collection of physical media such as CDs and vinyl records. A CD of Kelly Clarkson’s “All I Ever Wanted,” which was gifted to her for her sixth Christmas, sparked her interest in collecting physical media. Since then, Eckstein has collected over 100 CDs and displays them on a CD rack in her dorm at SF State.

Even with a large collection of CDs and vinyl, Eckstein enjoys how easily accessible and portable digital music streaming apps are, listening to about 70% digital music and 30% physical media, but she continues to collect physical media.

“When I listen to digital music I usually don’t just play an album. I know a lot of people do but I’m more into shuffling an array of music,” Eckstein said. “When I listen to physical media, I’m listening to the CD or vinyl in its entirety, and you can see the effort that somebody put into the order of songs, and also, you can just say that you own it. That’s your CD, but when you download it on Spotify or Apple Music, everyone has access to it.”

Collecting physical media can become expensive, which is one of the only things Eckstein doesn’t like about collecting physical media. Depending on the rarity of a new vinyl, the price point can range from $10 to $500. Physical media collectors can hunt for their favorite albums at thrift stores to try and save some money. Used vinyl at Community Thrift, located in San Francisco’s Mission District ranges between $1 to $3, and the only risk is the condition of the record.

Eckstein plans to buy a new CD tower to continue to grow her collection, as she tends to buy a new CD or two every time she goes somewhere that sells physical media. She also hopes that she can pass down her love of collecting to the future generations that she interacts with.

“Records […] were great technology when they were made, and they still are,’’ said Wintroud. ‘’There will always be a subsection of people who desire that. I think that we will grow to a certain point but I don’t think that we will ever be as big as digital media, but I don’t think that [physical media] is going away.’’