For over 55 years, SF State has been a hub of efforts to reform education, with students, faculty and the greater campus community actively participating in strikes and protests for decades.

In November 1968, students from the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front began striking in response to the suspension of George Murray, a teaching assistant and member of the Black Panther Party. Ann Robertson was a graduate student at the university, then called SF State College, when the strike began.

“I come from a background where my family wasn’t political at all,” said Robertson. “So all of this was incredibly new to me.”

Most of Robertson’s classes were canceled, but one of her philosophy professors did not participate in the strike, so she attended his class.

“I was more on the sidelines, just beginning to get politicized myself,” said Robertson. “But when I came back [to teach at SF State], I actually had a very good relationship with most of the faculty in the philosophy department. When I was a student, I was kind of critical of them for not being more radical.”

Robertson’s politicization ultimately led her to become involved with the California Faculty Association, the union that represents around 29,000 professors, lecturers, librarians, counselors and coaches at all 23 CSUs.

Before the CFA was established statewide, the American Federation of Teachers was the union representing faculty at SF State.

Arthur Bierman, co-founder of the SF State AFT chapter, wrote a letter to the San Francisco Bay Guardian in December 1968 stating that SF State was in crisis, despite the image then-interim university president S.I. Hayakawa and his administration presented.

“The workload at [SF] State is 50% higher than comparable colleges in other states; instructors’ pay is 20–30% lower; instructors have no contract; and the Academic Senate’s decisions have been violated frequently at will by the chancellor and trustees,” Bierman wrote.

On Jan. 6, 1969, the AFT went on strike—over 350 teachers formed a picket line near the entrance of the campus at 19th and Holloway Avenues to prevent students from going to class by crossing the picket line.

“The union was sympathetic to the Black students,” said Bierman in an interview in 1992. “The main reasoning along these lines was that the third-world people were not going to escape their lower position in the economic scale and acceptance into society unless they got themselves educated.”

Robertson added that alongside the support and solidarity for the Black Student Union, the AFT was concerned about possible legal repercussions for striking as state law prohibited state employees from striking or using collective bargaining.

The AFT demanded SF State administration settle the 15 demands of the BSU and TWLF and establish rules for faculty involvement in decisions around unit and class assignments and amnesty for all faculty, students and staff who participated in the strike.

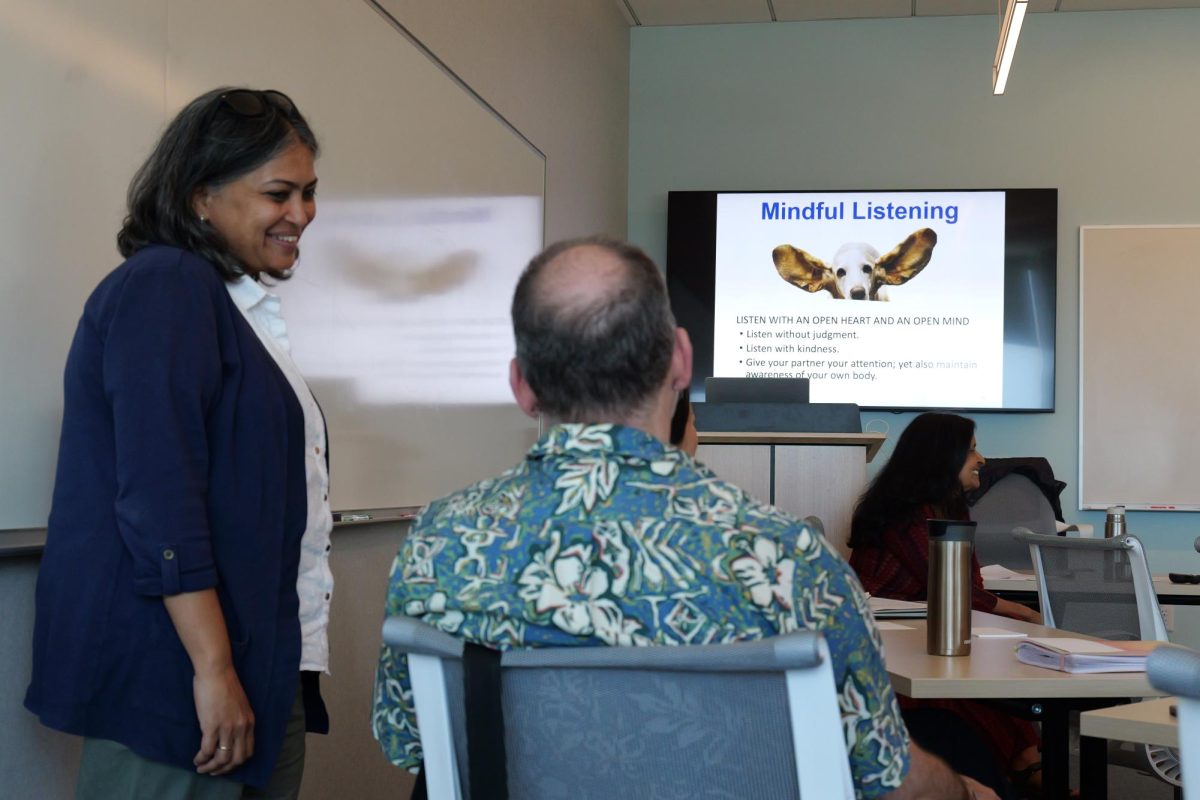

Mark Allan Davis, CFA-SFSU racial and social justice representative, emphasized the critical importance of faculty unions engaging with students to tackle their demands and that students are just as fired up and engaged now as they were in the 1960s.

“Tuition hikes, the war in Gaza, the attack on [Critical Race Theory] and LGBTQ+ rights—all of it is right for students just as much as it was back then to organize and participate and engage,” he said. “We wouldn’t have had such a successful December 5 strike on this campus if it wasn’t for the support of the students.”

Davis noted one main difference: students and faculty in the 1960s faced issues that were more at the forefront. At the same time, today’s campus community deals with more distractions that prevent them from tackling as many issues.

“Students shouldn’t have to pay tuition because education is a public good,” said Robertson. “The entire society benefits when people are well-educated, so it makes sense to help society pay for it, not the individual.”

The AFT quickly reached a tentative agreement on Feb. 25, 1969, which the union approved on March 2.

The faculty returned to work two days later, with provisions to dismiss disciplinary actions against faculty members who participated in the strike, funding and staffing for the Department and School of Africana Studies, now the College of Ethnic Studies.

Though the faculty was able to get most of their demands met by SF State administration, the AFT failed to settle the demands set by students. The BSU and TWLF continued to strike until March 21, 1969, reaching an agreement after 133 days.

Robertson noted several parallels between the AFT and CFA strikes. Still, she believes that solidarity between faculty and students was stronger in the 1960s and that today’s faculty and students are looking to rebuild that strong alliance.

“It’s real power. That’s where our power comes from—it comes from acting collectively,”

Robertson said. “Because if we’re all doing something together, which we’ve decided on democratically, we can begin to control what happens at the university.”